Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Brent Tarter, Marianne E. Julienne and Barbara C. Batson

All rights reserved

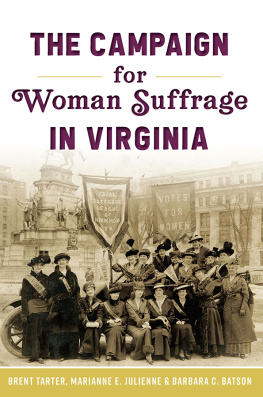

The Votes for Women banner courtesy of Sophie Meredith Sides Cowan.

First published 2020

E-Book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43966.908.2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019951906

Print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.419.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

One hundred years ago, American women won the right to vote with the passage and subsequent ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The movement to secure woman suffrage began in the mid-nineteenth century, but it took many decades of hard work before a majority of Americans fully acknowledged that a country that denied half its population a voice in choosing their leaders and shaping the nations future could never be regarded as a true democracy.

The story of the national effort to secure woman suffrage is a well-known and important one. The names of those who led the movementSusan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Carrie Chapman Catt, among othersare familiar to anyone who has taken a high school or college course in American history. The campaign for woman suffrage would not have succeeded, however, if its only focus had been at the national level, on Congress and the White House. The work that women did in statehouses across the country to persuade their local representatives to support the cause was crucial in turning the tide of opinion. Women banded together in their state capitals but also in their home communities, large and small, to make their case with their friends and neighbors. Over time, their work ensured the grass-roots support that state and national elected officials could no longer ignore.

The Campaign for Woman Suffrage in Virginia describes in vivid detail how the suffrage movement unfolded in a key southern state where traditional views about women (and much else) held sway. Despite the challenges they faced, Virginia suffragists created an effective state organization, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, that coordinated the efforts of scores of local chapters located not only in urban areas but surprisingly in remote and rural areas of the state as well. The suffragists in this book are for the most part unknown to historians of Virginia, and their achievements have not been properly understood. Indeed, they succeeded rather than failed in their original objective of persuading the General Assembly to propose a woman suffrage amendment to the state constitution

This book helps us understand who these women were and how they developed the practical arguments and strategies they believed would work with those they needed to convince. Here we also see the divergent opinions of white Virginia suffragists as they debated whether their goal should be an amendment to the state or to the federal constitution, whether their tactics should rely on persuasion or militancy and how to address the issue of race in a state that had substantially disfranchised its black male citizens. Because African American women had to work more quietly than their white counterparts to avoid a backlash that might jeopardize the cause, their contributions to the suffrage movement in Virginia have often been overlooked. The Campaign for Woman Suffrage in Virginia presents their efforts on behalf of social justice and suffrage as an important part of the story.

Virginia did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952, a symbolic gesture, as Virginia women had been voting and participating in government affairs for more than three decades. By that time, many Virginia women profiled here had made their mark in the states public life.

Sandra Gioia Treadway

Librarian of Virginia

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank former Library of Virginia archivist Jennifer Davis McDaid, who organized the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia Records and created the first finding aid; Library of Virginia archivist Trenton E. Hizer, who prepared the Equal Suffrage League Records for scanning and prepared a new finding aid for the collection; Kathleen Jordan, digital initiatives and web presence director of the Library of Virginia, who facilitated the digitizing of the records; Sophie Meredith Sides Cowan of Blue Hill, Maine, and Tucson, Arizona, who preserved and shared with the Library of Virginia the Virginia branch records of the Congressional Union/National Womans Party; all the people who volunteered to research and write biographies of Virginia suffragists (and a few women who opposed woman suffrage) for the Library of Virginias online Dictionary of Virginia Biography; and Sandra G. Treadway, Megan Taylor Shockley, Frances S. Pollard, Lauranett Lee, Gregg D. Kimball, Catherine Fitzgerald Wyatt, John G. Deal and Leila Christenbury, who read the first draft of the book and offered valuable suggestions.

LET OUR VOTE BE CAST

AN INTRODUCTION

This is the proudest day of my life! a woman in Norfolk, Virginia, exclaimed on November 2, 1920, as she prepared to vote for the first time. The proudest day? asked another woman who was waiting with her in line at the polling place. Why, have you forgotten your wedding day?

No, the first woman replied, but the Lord gave me the graces that won for me a wedding day, but it took more than God-given graces to bring about this day!

It had taken many years of hard work by deeply committed women in their hometown of Norfolk, elsewhere in Virginia and throughout the United States. About seventy-five or eighty thousand women, both black and white, eagerly went to the polls in Virginia that day to vote in what everybody agreed was a remarkable event, a turning point in Virginia historya turning point in American history, too, because on that day for the first time, women in every state exercised the right to vote.

Women who campaigned for woman suffrage regarded the vote both as a natural right of citizenship and as a tool with which to achieve political objectives. Many of them worked for changes in local, state and national laws for the benefit of women and children to improve education, public health and conditions under which working men and women lived. Lillie Mary Barbour, a Roanoke member of the United Garment Workers of America and an advocate for working women, explained during the campaign that the ballot in our hands is the only thing to help us.

The woman suffrage movement was one of a sequence of campaigns that different groups of Americans fought to make a reality out of the implied promises of the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Declaration of Rights that all men were created equal. When Thomas Jefferson and George Mason wrote those influential documents in 1776, they used the word men and referred to members of the political nationadult, white men who owned propertybut other Americans sought to be included. Much of the history of the United States and of Virginia can be understood as those other Americans efforts to make a reality of the revolutionary promise. That promise drove the campaign for the abolition of slavery and for universal white manhood suffrage before the Civil War, to enfranchise African American men after the war, to win the vote for women late in the nineteenth and early in the twentieth centuries and powered the civil rights, American Indian and womens movements later in the twentieth century.