Preface

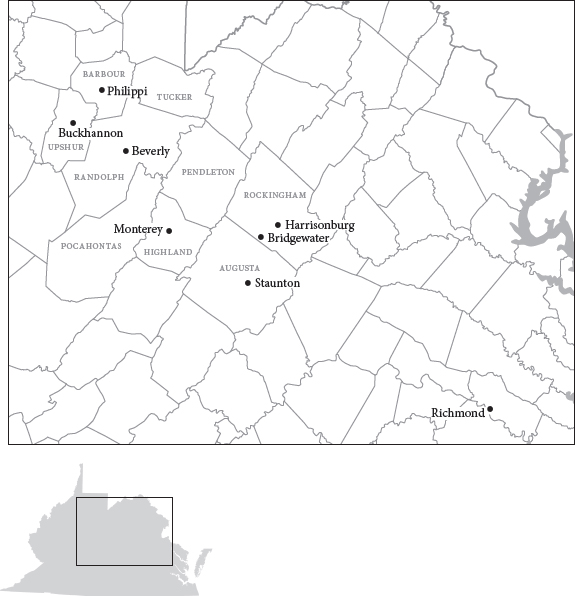

Every folder, box of manuscripts, bound volume of historic records, and reel of microfilm in every research library contains stories about people. This story comes in large part from a reel of microfilm of the Berlin-Martz Family Papers in the Library of Virginia. It is the story of George William Berlin and Susan Miranda Holt Berlin, of Buckhannon, in Upshur County, Virginia, one of the counties that in 1863 became part of West Virginia. The story begins in February 1861, when he traveled to Richmond to serve in the state convention called to deal with the secession crisis. It ends after October 1862, when they were reunited after being twice separated by political and military crises.

This true story is derived in large part from the incomplete file of surviving letters that they exchanged during their separations. Because there is nothing so valuable for trying to understand how past events affected people as the words of the people who lived through the events, the narrative contains extended excerpts from their letters. The words that they wrote and the ways that they described their experiences and their hopes and fears give valuable insights into their beliefs and emotions. Through their letters, they told their stories to each other, and to a large extent the letters tell their stories to us, too. Other family papers, public records, and the letters and diaries of other people enrich the context and fill in some of the gaps, particularly with respect to the political choices that George Berlin faced in 1861, choices that had dramatic consequences for him and his family.

The story of George and Susan Berlin and their family is of comparatively ordinary white mountain Southerners and what they did on the eve of the Civil War and during its first year and a half. The Berlins were more prosperous than most of their neighbors, but they were not wealthy. He was an aspiring attorney living in a town, not a great planter, not an independent small farmer, not a poor laboring man. In that, the Berlins were not stereotypical white Southerners, but during the middle decades of the nineteenth century professional men in small Southern towns were an increasingly numerous and important class of white Southerners. George and Susan Berlin owned no slaves, but they hired an enslaved man and young white girls or enslaved women to assist with work in the garden and at household labor, setting them just a notch above most of their neighbors and contemporaries in the mountains of northwestern Virginia and involving them personally in the economy of slavery. The Berlins may also have been better educated than some of their neighbors, and they had traveled back and forth across the mountains to eastern Virginia often enough that they may have had a wider acquaintance than their neighbors with the people and geography of western Virginia.

Virginia places that played a part in the lives of George and Susan Berlin in 186162. (Map by Chris Harrison)

In 1861 George and Susan Berlin lived in a large, loose family group consisting of their five children; his brother and her sister, who were married to each other, had a large number of children, and also resided in Buckhannon; and also her parents and several brothers and sisters, who lived in nearby Philippi, in Barbour County, or sometimes with them. The story of George and Susan Berlin is therefore, in part, also a story of their extended family. In 1861 they and millions of other Americans got caught up in very remarkable events. Their story is about how extraordinary events shaped the lives of comparatively ordinary people and how they acted in those new circumstances.

Members of the Berlin family were not wholly consumed by the secession crisis and the war even as it directly altered their lives. They continued to take care of their own personal and family affairs early in 1861 as if the Civil War was not going to happen. The ordinary business of earning a living, bringing up their children, and helping their in-laws remained at the center of their attentions. Those activities and connections were the most important factors that governed how they lived their lives. The secession of Virginia and the resulting war changed the context in which they tried to continue to live their lives. Extraordinary events of extraordinary times then disrupted the ordinary lives of rather ordinary people.

Dramatic historic events happen in a context that is different for every person involved. The story of the Berlins is unique, but their story shares important large themes with the stories of millions of other Americans and their families who had their own unique experiences during those same extraordinary times. It is a very personal story, which is why it is important to read their words carefully and at length. How they wrote, and what they wrote, are both important. Consequently, I have employed a narrative prose style adapted to their speaking and writing styles to help readers into and out of George and Susan Berlins words and thoughts, the better to understand what the extraordinary events meant to them.

I have quoted their letters as nearly verbatim ac litteratim as possible, including the many misspellings, run-on sentences, and other imperfections that their letters include. In some instances it is difficult to determine whether the writer intended a capital or lowercase letter, and in those instances I have rendered the characters in lowercase type except at the beginnings of sentences. Both writers added postscripts or made additions to their letters, sometimes squeezing text into narrow margins or writing them on attached slips of paper. Unless it is clear from the context or by the presence of asterisks or carets in the originals, I have interpreted those additions as postscripts.

The letters have never before been published, and with a few exceptions no other historian has used them. My colleagues and I at the Library of Virginia reproduced one letter from George Berlin in our Union or Secession: Virginians Decide website in 2010; Clarence E. May had access to the papers and mentioned them in passing in his Life under Four Flags in the North River Basin of Virginia (1976); and my friend and colleague Daphne S. Gentry used them to prepare the entry on George W. Berlin for volume one of the Dictionary of Virginia Biography (1998), of which she was an assistant editor before her retirement and subsequent death in 2007.

She tracked down the family papers and brought them to the attention of archivists at the Library of Virginia, who arranged for the collection to be microfilmed and preserved as the Berlin-Martz Family Papers, Acc. 36271, Miscellaneous Microfilm reel 2051 in the Library of Virginia in Richmond.