Gerrymanders

Gerrymanders

How Redistricting Has Protected Slavery, White Supremacy, and Partisan Minorities in Virginia

Brent Tarter

University of Virginia Press

Charlottesville and London

University of Virginia Press

2019 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2019

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tarter, Brent, author.

Title: Gerrymanders : how redistricting has protected slavery, White supremacy, and partisan minorities in Virginia / Brent Tarter.

Description: Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019006667 (print) | LCCN 2019009062 (ebook) | ISBN 9780813943213 (ebook) | ISBN 9780813943206 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : GerrymanderingVirginia. | Election districtsVirginia. | Political cultureVirginia. | VirginiaPolitics and government.

Classification: LCC JK 1343. V 3 (ebook) | LCC JK 1343. V 3 T 37 2019 (print) | DDC 328.73/0734509755dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006667

Maps by Nat Case, INCase, LLC

Cover design: David Drummond, adapting map of 1991 congressional districts by Nat Case

Contents

For reading an early draft and making valuable suggestions I thank:

Toni-Michelle C. Travis, professor of political science at George Mason University, a frequent commentator on Virginia politics and government, and editor of the Almanac of Virginia Politics;

J. Douglas Smith, of Colburn Conservatory, author of the prize-winning Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics, and Citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia (2002) and of On Democracys Doorstep: The Inside Story of How the Supreme Court Brought One Person, One Vote to the United States (2014); and

Jeff E. Schapiro, a political analyst who has written often about gerrymandering in his regular column for the Richmond Times-Dispatch; also

Richard Holway, acquisitions editor at the University of Virginia Press, who was enthusiastic about the project from the very beginning; and

Nat Case who prepared the maps.

Gerrymanders

The Gerrymander Monster

This short book presents for the first time the full history of more than two centuries of the gerrymandering of legislative and congressional districts in Virginia. A gerrymander is a deliberate drawing of electoral districts to give an advantage to one political candidate or party, to influence who gets elected and who does not, and thereby to further or hinder the chances of particular public policies being adopted or defeated. Gerrymanders have taken place at all levels of government, from district lines for the election of members of Congress and state legislatures to city and county governing bodies, school boards, and judges in some states. Most of the scholarship on gerrymanders focuses on how gerrymanders have influenced which political party controls Congress, but gerrymanders of state legislative districts are arguably even more important. In most states, legislatures not only draw congressional district lines but also draw their own district lines as well as, sometimes, district lines for other elective bodies. Gerrymandered legislatures are therefore of the utmost consequence in local, state, and national politics and government. Gerrymanders affect our taxes, our public schools, and every other public policy decision.

Partisan gerrymandering to give one political party or group a long-term advantage is not essentially different from allowing changes in the rules of baseball to give the home team four strikes per out and four outs per inning but limit visiting teams to three strikes and three outs. Teams limited to three strikes and three outs could theoretically still win and occasionally would, but they would be at a serious and permanent disadvantage. The rules of baseball guarantee that both teams and all players have a free and equal chance to win by virtue of their skills. Partisan gerrymanders, however, disrupt or prevent a fair electoral process that should allow a majority of voters to elect the candidates who best represent their beliefs and interests. Legislators who draw electoral district lines are always the home team. That is what makes partisan gerrymanders extremely important and almost always unpopular except among the politicians who benefit from them. As is often said, in a representative democracy voters should select their representatives; representatives should not select their votersbut that has often been the case.

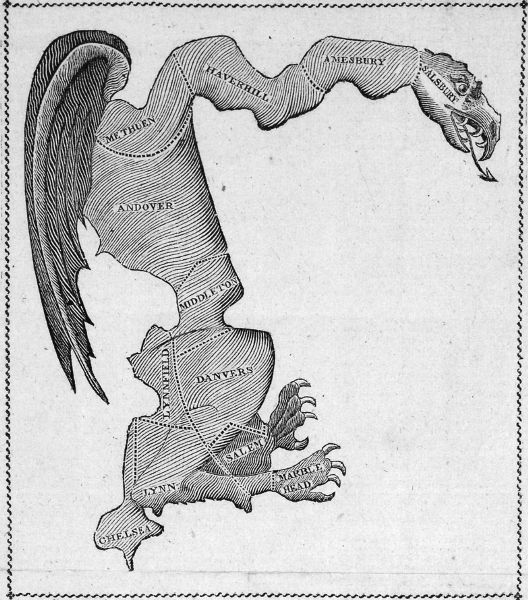

Just such an event led to the coining of the word gerrymander. It entered the English language on March 26, 1812, in a Boston Gazette article that showed that the peculiar shape of a new Massachusetts Senate district resembled a dragon, a salamander, or a GERRY-MANDER . The new word for the new species of Monster included the surname of Governor Elbridge Gerry, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who was elected vice president of the United States later that year. His allies in the Massachusetts General Court (the state legislature) designed the district in hopes of retaining a Senate majority for their political faction. The pronunciation of the word has since changed. Gerrys name was pronounced with a hard g, but the word for the practice is pronounced with a soft g.

In the 1907 book The Rise and Development of the Gerrymander, the first scholarly study of the subject, Elmer C. Griffith described the practice as a political device that sets aside the will of the popular majority. It is a species of fraud, deception, and trickery which menaces the perpetuity of the Republic of the United States. The gerrymander, Griffith repeated, is a corrupt Supreme Court of the United States in the 1960s that required that the principle of one person, one vote replace centuries of political practices that had given some groups of people, regions, or interests advantage over others in voting and representation.

Fig. 1. Detail of a broadside that reproduced the March 26, 1812, Boston Gazette image and description of the original gerrymander. (Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society)

Gerrymanders have a long but overlooked history in Virginia. Legal scholars, political scientists, and journalists have written about several important episodes, but historians have largely ignored the subject, and nobody has connected to dots to see the larger picture and all its consequences. That is one purpose of this book. It is also intended to assist people who are not experts on this subject to understand the complex legal issues on the eve of the 2021 session of the General Assembly that will redraw district lines for the state Senate and House of Delegates and also for the U.S. House of Representatives.

In addition to the purely partisan purposes most people think of when they first encounter the word, gerrymanders in Virginia have protected special interests, such as those of landowners, slave owners, white supremacy, and minority rule. Virginia gerrymanders have taken many forms. Some have been very conspicuous, but some were almost invisible. Some have been obviously deliberate, but others appeared inadvertent. In redistricting, gerrymanders can operate at the micro level through subtle, small adjustments of one or a few district lines. In reapportionment, they can also operate at the macro level, such as constitutional conventions imposed on Virginia between the American Revolution and the American Civil War as well as in legislated schemes of representation in the state in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Many aspects of modern Virginia politics and the operations and consequences of redistricting and reapportionment appear in a clearer light when viewed in the context of colonial and nineteenth-century practices, but legal scholarship and judicial opinions usually omit or misrepresent the long historical context. In Virginia and elsewhere restrictions on the suffrage must also be kept constantly in mind