INTRODUCTION

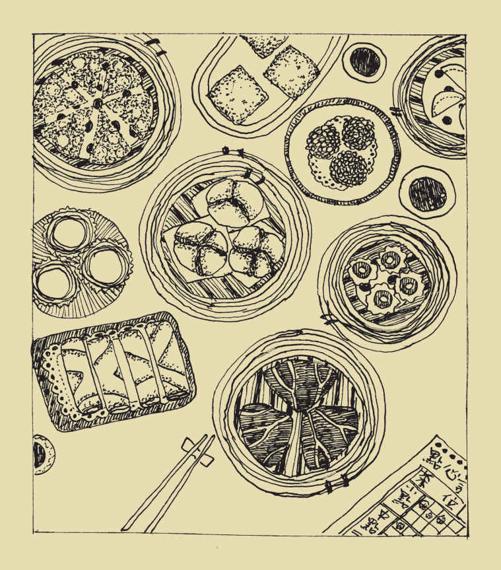

Welcome to the delicious world of dim sum. This is an exquisitely leisurely way to brunch, a meal that, when done right, can easily stretch out for a couple of hours into the afternoon. Each one- or two-bite morsel of dim sum is essentially a small packet of unique flavorsjust enough to grab your attention and whet the appetitebut small enough that you can move on to the next tantalizing dish before your palate becomes bored.

This book explores the Cantonese form of dim sum, which was born in the teahouses of Southern Chinaspecifically, the capital city of Guangzhou that straddles the great Pearl Riverabout two centuries ago. Of course, the history of dim sum stretches back much farther than that (jiaozi-like dumplings, for example, were discovered in a Tang dynasty tomb dating from thirteen hundred years ago), and many other parts of the country boast of wonderful arrays of teatime snacks and petite sweets. However, I would have to agree with those who claim that the culinary art form known as dim sum reached its absolute pinnacle in Guangzhou.

Perhaps the secret lies in the land. Located on the lush, fertile plains of southern Guangdong, this area has an almost endless selection of vegetables, starches, fruits, animals, crustaceans, and seafood. Or maybe its the people, for Guangdong has been the destination for immigrants from all over the country who longed for more peaceful lives and who made Guangzhou synonymous with gracious living. Or maybe its the tropical weather, the type of climate that encourages a person to laze in the shade with a hot pot of tea and some savory snacks, a trickle of water and the rattle of bamboo leaves in the warm wind coming together to form a natural lullaby. Or maybe it is because Guangzhou was a nexus between East and West, as well as North and South, a place where foreign culinary inspiration gave birth to marvelous ideas in the kitchen, while imperial and Muslim tastes added their own rich notes to this culinary symphony. Or maybe it is because all of these great food traditions eventually made their way down the Pearl River to Hong Kong, where ancient history crashed into the modern world, and many dim sum dishes evolved into their delicious, present-day incarnations.

Whatever the reasons, dim sum remains one of the most delightful ways ever invented for whiling away a few hours in the middle of the day. And despite what some think, dim sum is a whole lot more than dumplings, a sort of catchall English term for anything vaguely starchy and small in the dim sum brigade. Theres nothing inherently wrong, of course, with calling these dumplings, but its sort of like labeling scarlet, chartreuse, and bronze simply colors, when they are so much more thrilling than that. The fact is that dim sum covers an intense spectrum of flavors, aromas, textures, and ingredients, and they are very much worth getting to know on a personal basis.

Which is where The Dim Sum Field Guide fits in. My hope is that this book will inspire you to explore the many offerings in dim sum teahouses, whether you carry it with you on your next field excursion, or simply flip through it at home. If dim sum ends up giving you even half the pleasure it has handed to me, I know you will be a dedicated fan for the rest of your life.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF DIM SUM

Dim sum is the Cantonese pronunciation of dinxn, a verb that a thousand years ago merely meant to eat a little something. It was not until somewhere around the year 1300 that dinxn evolved into a noun meaning snacks or very light meals, a definition that has more or less remained unchanged to this day.

Dim sum probably had their earliest origins as tea snacks in the north around one thousand years ago, but it took another five centuries before Southern Chinaand particularly Guangdongwas reveling in its very own versions. Nearly every area of China has iconic snack traditions; however, the demarcation between North and South in almost all discussion of Chinas foods has been (and probably always will be) the Yangtze River because the climate, ingredients, geography, aesthetics, languages, and cultures of the two halves are just so very different.

What this means when it comes to food is that Northern China has traditionally reveled in the heartier, wheat-based snacks of the ethnic Muslims there (known to the Chinese as the Hui people), such as the stuffed buns called were handed down to us as culinary heirlooms from the imperial kitchens of Beijings Forbidden City. In the warm lands along the Pearl River, though, rice dough and tropical ingredients such as taro and coconut pop up just as much in the local dim sum as wheat.

Guangdongs most famous dim sum most likely evolved from the sophisticated treats served in elegant salons along the Yangtze and were greatly influenced by dishes that wound their way south from the capital in Changan (todays Xian) in the North, which might explain the presence of and many other pasta or raised wheat dough dishes in the Cantonese dim sum repertoire. Add to that the increased contact and trade with the West a couple of hundred years ago, which led to foreign touches like custard and curry, and suddenly the cultural and historical tendrils that shaped this scintillating branch of Cantonese cuisine make a whole lot of sense.

HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE

Dining on dim sum is easy once you get the basics down pat. And this book is going to help you do that.

First, keep in mind that the names of these dishesespecially the English oneswill vary widely from place to place once you get out into the real world. For example, you might find called shrimp and pork dumplings or shui mai or shiu mai or sui mai or shao mai or some other combination of these words, because some people have just winged it over the years when it came to transposing Chinese pronunciations into English. That is one of the reasons why we have so many illustrations in this book, as well as the name of each dish in Mandarin, Cantonese, and traditional Chinese characters. And so, the easiest way to get what you want the first couple of times you eat at a dim sum teahouse is to simply point at the