FOREWORD

On Mastery and Leadership

I BEGAN MY CAREER as a young artist working in clay in the seventies. The field was nascent even though the history of the medium was ancient. Contemporary ceramics was dominated by the vessel on the East Coast whereas figural ceramics was prominent on the West Coast. Studio craft provided an entry for Post-War artists and the Baby Boomer generation through independent, entrepreneurial models for their creative practices. I founded my first studio and gallery in partnership with other women artists, all of us working from a place of personal devotion to the medium of clay.

Opportunities to learn were based only in traditional academic settings or community workshops, while inspiration came from print. Books and magazines featured images of seminal works by young artists who later became renowned masters, and these images became burned into our minds, alongside groundbreaking photos of civil rights protests and space exploration.

In and out of ceramics, feminism and identity became both subject and content for artists whose figural and narrative works provided a platform for self-expression. The Guerilla Girls called out gender-based disparities with politically charged posters that began, and continue, to fuel institutional change. Linda Nochlins pivotal 1971 ARTnews essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? questioned the exclusion of women from art history and pointed the finger at the authorship of the canon. Through this period, leading ceramic artists Betty Woodman and Ruth Duckworth pushed past the vessel into sculpture and Viola Frey produced monumental figures. Beatrice Wood and Coille Hooven used the figure to both poke fun at gendered norms and deliver social commentary. Judy Chicagos epic multimedia The Dinner Party involved 129 people in a collaborative production that celebrated and commemorated 1,038 women throughout history via an installation of thirty-nine ceramic place settings, textiles, and site activations.

By the end of the nineties, when Cristina Crdova began her career, young artists were freer to explore and move between established categories and produce work without many of the restrictions imposed on their predecessors. Women were gaining positions of leadership as educators and artists; likewise, they were offered more exhibition opportunities in galleries and museums. Popular movements rise and fade, and by the 2000s, figural work began its rise again, delivering personal narratives from diverse perspectives to expanding audiences. From Woodmans 2006 solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through to Simone Leighs historic representation of the United States at the 2022 Venice Biennale, there are still many firsts happening in ceramics and many gender and race-based barriers being broken.

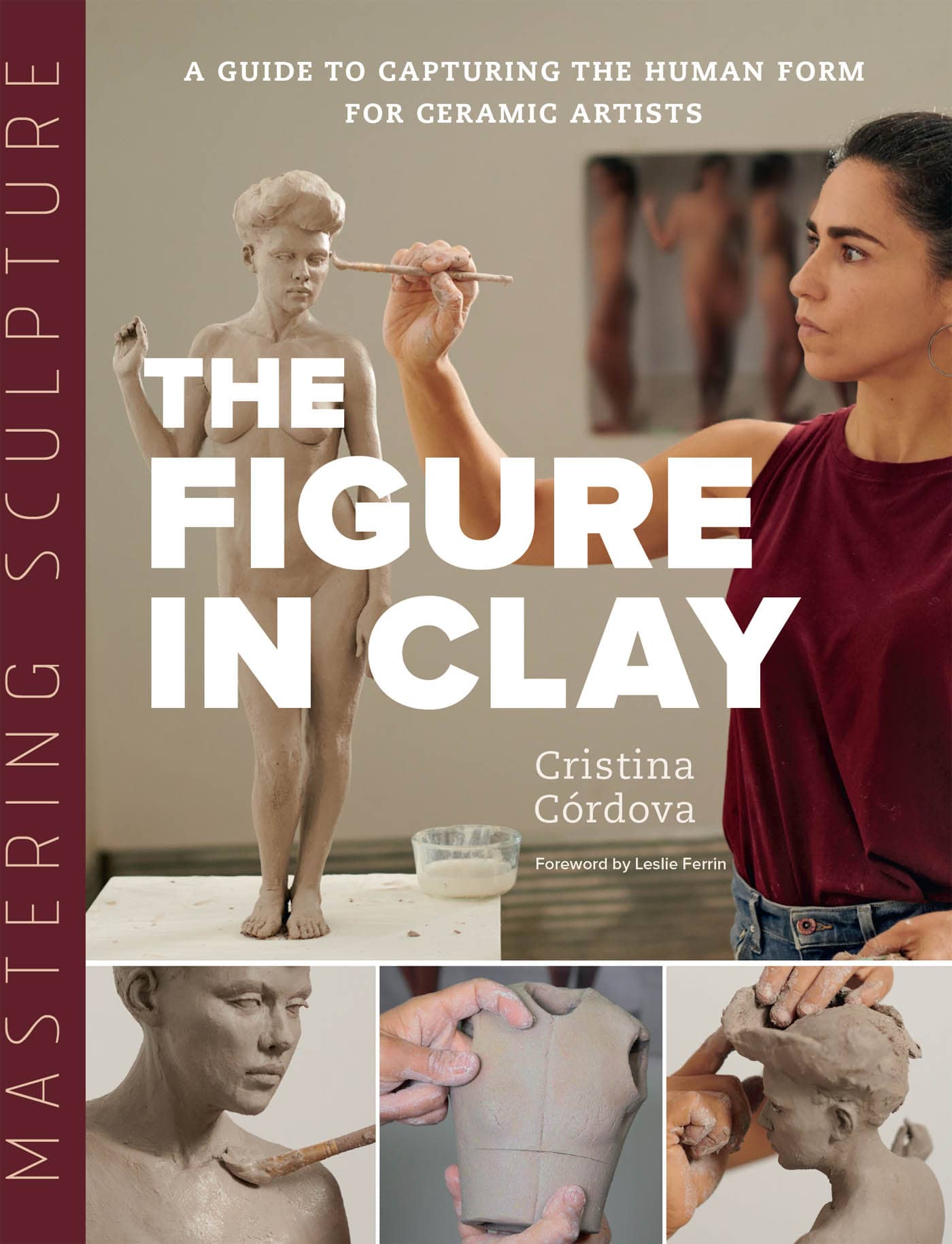

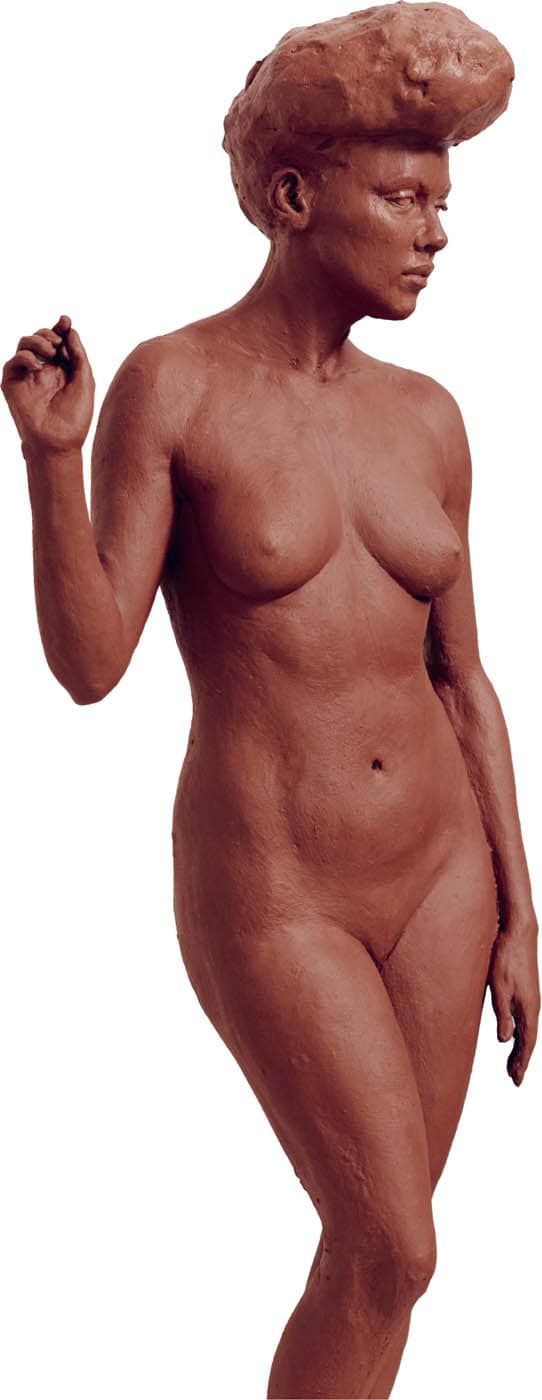

Of course, the changing history of clay and ceramics, and the contemporary social impact of figuration is larger than what weve touched on here. However, a good cross-section of this history is highlighted throughout The Figure in Clay, as Cristina has filled these pages with a beautiful combination of instruction and inspiration. Throughout her career, Ive had the privilege to work with Cristina and so many other artists featured in this book. Ive watched them individually and collectively raise the bar and push beyond the status quo. Ive seen their works inspire one another, feed exploration through teaching, join forces to celebrate triumphs of technical challenge, and collaborate in a community known for mutual support. Cristina is widely recognized through major grants and exhibitions and, now at mid-career, her work is seen in context with other sculptors who are current leaders in the art field.

Mastery and leadership are not always synonymous, but Cristina possesses both. What makes an artist both a master of her medium and a leader in her field? Dedication to the studio, of course, but also a spirit of generosity. Cristina is so influential today because of her powerful sculptures, certainly, but also because she has given very deeply as an educator. The result is a strengthening of the figure in clay that is felt throughout the field. By dedicating the time to document her process, share it through teaching, and now through this book, she provides a path for others to follow, to learn from, and to be inspired by.

The Figure in Clay is both a summary of many years of dedication and hard work and a detailed step-by-step guide to aligning thought, eye, and hand. It is very clear why her teaching methods continue to be so influential in the lives and careers of a new generation of figurative sculptors. This book, like the volumes that influenced a generation forty years ago, will continue to influence the field for generations to come.

LESLIE FERRIN