THE U.S. ARMY COOKS MANUAL

THE U.S. ARMY COOKS MANUAL

Edited by R. Sheppard

Published in Great Britain and

the United States of America in 2018 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

Casemate Publishers 2018

Hardback Edition: 978-1-61200-470-9

Digital Edition: 978-1-61200-471-6

Mobi Edition: 978-1-61200-471-6

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishing.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Fax (01865) 794449

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

Cover design by Katie Gabriel Allen.

Frontispiece: US Army in the trenches, World War I.

The recipes and instructions in this book are provided for information only. The publisher assumes no responsibility of liability of any damage incurred resulting from following any of the recipes or instructions printed in this book.

INTRODUCTION

The feeding of an army is a matter of the most vital importance, and demands the earliest attention of the general entrusted with the campaign.

General Sherman, Memoirs

Food sustains the immense machinery of war

John C. Calhoun, Secretary of War, 181725

N apoleon may or may not have actually uttered the immortal phrase An army marches on its stomach, but any soldier will tell you its true. Throughout history, an army with insufficient or inadequate food during a campaign is instantly at a huge disadvantage: the Roman writer Vegetius said that an army without supplies of grain and other provision exposed itself to defeat before even entering battle. In some cases, the outcome of a war could come down to which army had the better breakfast.

While a number of treatises on how to feed armies on the move appeared in several countries during the nineteenth century, it only tended to appear on a national political agenda when the existing system had completely failed the men flighting in the field e.g. when the British suffered from major supply issues in the Crimea. The introduction to The Provisioning of the Modern Army in the Field (1909) noted that: The fact that in this country practically no books have been published on this important subject would seem to indicate that the public and the service are both indifferent to the matter, except spasmodically when attention is drawn to it by reports of suffering. Periods of peace afford no opportunities for practical experience, and indifference to a subject indicates lack of familiarity, and this because the incentive to study and preparation has not been made imperative.

Supplying the army at war had necessarily been a concern in America even before the declaration of independence, and Congress would approve several methods before a reliable system developed. As the nineteenth century progressed, the army was venturing farther afield, requiring supplies to be transported farther and preserved for longer, and by the turn of the twentieth century, the army was operating overseas in different climates, which offered further challenges. When food reached the men, it then had to be turned into palatable meals. When in camp for long periods of time the men might receive soft bread from the bakehouse, and meals from a field kitchen but most of the time in the field mealtimes meant huddles of tired men around camp fires, trying to create something edible (and safe) out of their rather uninspiring rations and with only limited utensils. Things came to a head during the Civil War when senior officers realized that the health of their men was being badly affected by their amateurish attempts at cooking. Manuals, and eventually training, followed, and the increased understanding of nutritionand how soldiers could be provided with healthy and enticing meals in the garrison, in the field, and in transitevident in the 1916 manual shows what progress had been made in just under a century and a half. The sophistication of the system would of course be taken to the next level in the following war.

This book does not pretend in any way to be a complete history of food in the U.S. Army (for some examples see the bibliography), but rather an insight into what they ate, the types of meals they cooked and how, through the manuals and reports produced by or for the U.S. Army.

CHAPTER 1

FEEDING THE ARMY: 17751848

F eeding the Patriot soldiers in the field was of course a pressing concern for the Continental Congress, and a commissary-general of stores and provisions was created by resolution in 1775. The men were to be provided with a certain amount of food as a daily ration, yet could purchase other food and drink from the sutlers or other traders that accompanied the army. Out of necessity much of the ration was dried or salted, as was the military staple hardtack, a biscuit of flour and water that was cheap to make and long-lasting. But the best intentions of the Continental Congress were not enough to keep the men fed; soldiers did not receive their full ration complement, leaving them reliant on hunting, foraging, food parcels from home, and when desperate liberating provisions.

These early efforts of the commissary department met with so much dissatisfaction that there was an investigation by Congress in 1777, and a new system set up, with military agents purchasing the necessary provisions and ensuring these were delivered. Reforms then introduced forage masters, with contractors supplying rations to the mostly militia force. The new system was tested in the War of 1812, and it failedtroops on the Canadian frontier quickly ran short of rations as contractors failed to make deliveries. Though efforts were begun to improve the situation, a bill read in the Senate was postponed as peace took away the urgency and the matter of supplying the army was not considered again until the war against the Seminole Indians. The failure of contractors to supply rations in Georgia, despite having been paid in advance, meant military movements were delayed, and by January 1818 the situation was desperate. After finding that the militia in Georgia had been released from service, partly due to lack of provisions, thus leaving the frontier exposed, General Jackson wrote to the Secretary of War, Hon. John C. Calhoun in February 1818:

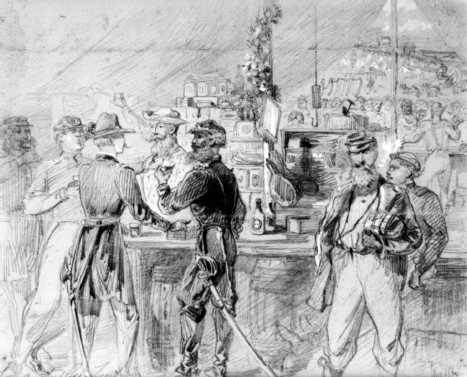

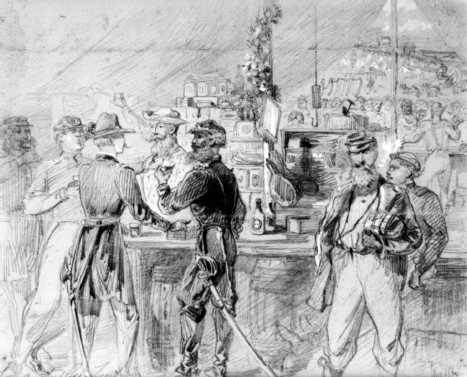

Detailed sketch by Arthur Lumley of the interior of a sutlers tent, with several fulllength portraits of unidentified officers drinking at the bar, August 1862. Arthur Lumley. Sutlers would continue to offer soldiers the option of supplementing their army rations until 1866, when the office was abolished, and replaced with post traders. (Library of Congress)