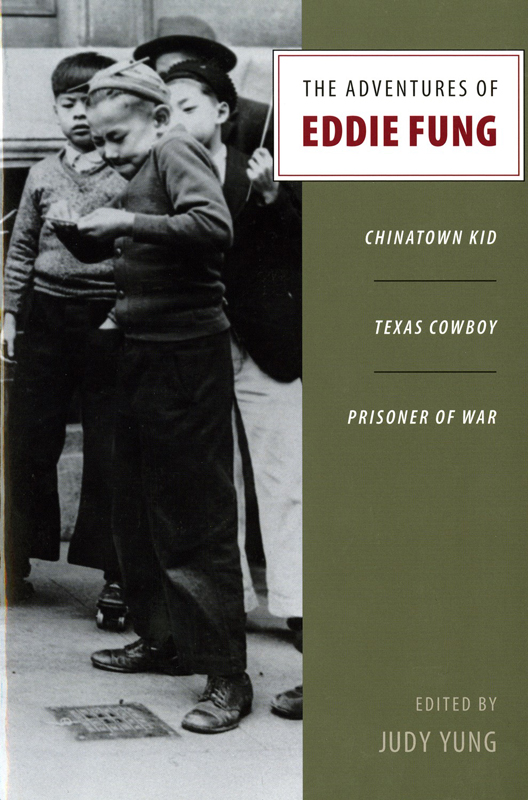

THE ADVENTURES OF EDDIE FUNG

CHINATOWN KID TEXAS COWBOY PRISONER OF WAR

EDITED BY JUDY YUNG

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

SEATTLE & LONDON

The Adventures of Eddie Fung is published with the assistance of a grant from the NAOMI B. PASCAL EDITORS ENDOWMENT, supported through the generosity of Janet and John Creighton, Patti Knowles, Mary McLellan Williams, and other donors.

Copyright 2007 by Judy Yung

Printed in the United States of America

Designed by Pamela Canell

13 12 11 10 09 08 5 4 3 2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

University of Washington Press

P.O. Box 50096, Seattle, WA 98145, U.S.A.

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fung, Eddie, 1922

The adventures of Eddie Fung : Chinatown kid, Texas cowboy, prisoner of war / edited by Judy Yung.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-295-98754-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Fung, Eddie, 1922 2. Chinese AmericansBiography. 3. Chinatown (San Francisco, Calif.)Biography. 4. San Francisco (Calif.)Biography. 5. CowboysTexasBiography. 6. World War, 19391945Participation, Chinese American. 7. World War, 19391945 Prisoners and prisons, Japanese. 8. SoldiersUnited StatesBiography. 9. Prisoners of war United StatesBiography. 10. Prisoners of warBurmaBiography.

I. Yung, Judy. II. Title.

E184.C5F86 2007 940.547252092dc22 [B] 2007019488

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and 90 percent recycled from at least 50 percent post-consumer waste. It meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

Cover photo: Eddie lighting a firecracker in Chinatown during the New Year celebration, 1935. Courtesy San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library.

ISBN 978-0-295-80205-3 (electronic)

FOR LOIS AND ALL MY BUDDIES IN THE LOST BATTALION

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I first met Eddie Fung in the summer of 2002. I was working on my fifth book, Chinese American Voices: From the Gold Rush to the Present, and I needed a World War II story, preferably one told from the perspective of a Chinese American veteran. I asked Colonel Bill Strobridge, a military historian who had conducted a study of Chinese Americans in World War II, if he could find me someone to interview. He came up with two possibilities. The first person had fought heroically in the front lines at Normandy, but he turned out to be a poor storyteller, one who gave short answers and stuck to the facts. Even though I conducted the interview in Chinese and did my best to make him feel comfortable, I could not get him to elaborate on the story or share his feelings on the matter. So I made arrangements to meet the second possibility, Eddie Fung, hoping that he would prove to be a more engaging storyteller.

We agreed to do the interview at Colonel Strobridges home in San Francisco. Prior to the interview, I did some background checking on Eddie Fung. I found out that he was an American-born Chinese who had grown up in San Francisco Chinatown like me, only he had preceded me by two decades. I was fifty-six years old, and he had just turned eighty. Colonel Strobridge also told me that Eddie had the dubious distinction of being the only Chinese American soldier to be captured by the Japanese during World War II and that he had worked on the Burma-Siam railroad made famous by the film Bridge on the River Kwai. Not knowing much about that history, I made a point of seeing the film before the interview. I was horrified by the brutal treatment of the prisoners under the Japanese and impressed by the courage and heroic actions of the POWs in the film. I hoped that Eddie would be forthcoming with details about how he as a Chinese American had fared and survived under such circumstances. The other interesting thing that I found out about Eddie was that he had run away from home to become a cowboy when he was sixteen. I was intrigueda Chinese American cowboy? Although it was the World War II story I needed, I decided I would start at the beginning with his family history in order to get a fuller picture of his life and to put his World War II experience into a larger context.

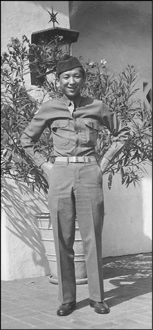

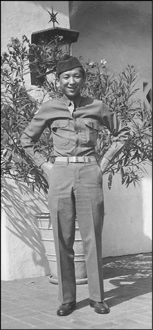

Having conducted over 400 interviews with Chinese Americans for various book projects by then, I thought I had allowed plenty of time for his storythree whole hours. This interview, however, turned out differently. A solidly built man of short stature5 feet 3 inches, and 120 pounds, to be exactEddie proved to be a natural storyteller with a fantastic memory for details, a precise way of expressing himself, a wonderful sense of humor, and a strong determination to tell the story right. In essence, he is every oral historians dream come true. He also proved to be an unusual interviewee in that he was both introspective and analytical in his responses. I soon found out that he had an indirect way of answering my questions, often recreating conversations and connecting specific incidents from the past to make his point. Regardless of how long-winded he got, Eddie was never boring. In fact, he held me spellbound at our first meeting, and before I knew it, three hours had passed and we had not even gotten to World War II! Somehow, I got the rest of the story out of him in the next two hours before I had to leave for my next appointment. He gave me a pile of books to read about POWs and the Burma-Siam railroad, and I promised to send him the transcript and edited story for his approval.

It was not until I transcribed his interview that I realized what a gold mine I had found. I thought, this had to be how historian Theodore Rosengarten must have felt when he happened upon Nate Shaw, an illiterate black sharecropper in Alabama with a story to tell, or how Alex Haley felt when he was asked to write Malcolm Xs autobiography. They both spent hundreds of hours interviewing their subjects and countless more writing their classic oral histories, All Gods Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw and The Autobiography of Malcolm X. I knew instinctively that there was a larger book to be written, although I did not think at the time that I was the right person to write it. Six months later, after I had completed a draft of his World War II story for Chinese American Voices, I contacted Eddie and hand-delivered the transcript and story to him for his approval. At the same time, I urged him to consider writing his memoirs, but he said with modesty that his story was not that unique or interesting. Besides, he said, Im not a writer. I continued, however, to press him, and suggested that we do a longer interview. If nothing else, I said, we could deposit the tapes and transcript in an archive for the historical record and for the use of other researchers. He reluctantly agreed. Retired and a recent widower, he had the time. For me, the time was right as well, because for the next nine months I was on sabbatical from my job as professor of American Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Until then, my research and writing had primarily focused on Chinese American women. I never thought that I would be working on a book about a mans life, but the opportunity was too good to pass up.