Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2021 by Suzanne Corbett and Deborah Reinhardt

All rights reserved

First published 2021

E-Book edition 2021

ISBN 978.1.43967.358.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021941053

Print Edition ISBN 978.1.46715.036.1

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is with gratitude that we offer this hearty huzzah for all of those who helped bring a taste of Missouris food history, along with its related recipes, to this project. We raise a glass to toast these individuals, while asking forgiveness for any oversights: Andy Hahn, executive director, Campbell House Museum; John Hoover, executive director, St. Louis Mercantile Library; Toby Carrig and Mary Elise Okenfuss, Ste. Genevive Tourism; Sara Hodge, curator, Herman T. Pott National Inland Waterways Library; Nicholas Fry, curator, John W. Barriger III National Railroad Library; Derek Klaus, director of communications, Visit KC; Carolyn Wells, Kansas City Barbeque Society; Susan Wade, public relations manager, Springfield Convention and Visitors Bureau; Daniel Johnson, executive director, Robidoux Row Museum; Marci Bennett, executive director, St. Joseph Convention & Visitors Bureau; Liz Coleman, communications manager, Missouri Division of Tourism; Isobel McGowan, Shakespeare Chateau; Jim Pallone and Jeff Keyasko, J C Wyatt House; Cierra Monsees, Missouri State Fair; Brian Lookout, Osage Nation/Ah Tha Tse Catering; Rich LoRusso, LoRussos Cucina; Monsignor Salvadore Polizzi, Hill Historian; Patty Held, Patty Held Wine Consulting; Nick Sacco, park ranger, and Julie Northrip, interpretation, education and volunteer program manager, Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site; David Newmann, interpretation program manager, Ste. Genevive National Historic Park; Doug Harding, park ranger, Gateway Arch National Park; Adam Criblez, associate professor, Southeast Missouri State University; Linda Williams, Windrush Farm Arts & Plants; Chef Rob Connoley, Bulrush Restaurant; Corrina Smith, executive director, Columbia Farmers Market; TaylorAnn Washburn, marketing specialist, Missouri Wine and Grape Board; Laura Burns and Frank Romano, the Parkmoor Drive-In; and photographer Jim Corbett III.

Many thanks to our acquisitions editor, Chad Rhoad, and the team at The History Press for their expertise and support. Finally, to our families, thank you for allowing us to be storytellers and supporting us over the years with your love and patience.

INTRODUCTION

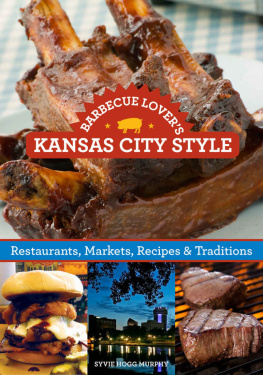

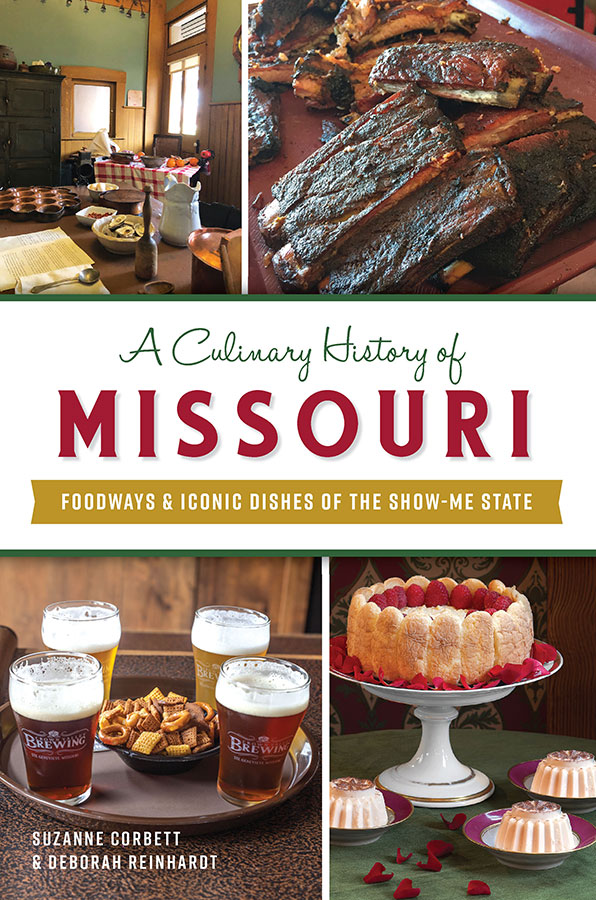

Anyone who came to Missouri could never claim that they left hungry. Since the states earliest beginnings, Missouris tables have been filled with a bountiful collection of food and drink. This book explores many of those foods, while offering a taste of Missouri via its foodways and recipe collection. This savory history celebrates cooks and chefs, brewers and winemakers, those who bottle soda and those who pour spirits. From the earliest colonial tables in Ste. Genevive to family farms and feasting on signature foods like Kansas City barbecue and St. Louis Gooey Butter Cake, we hope this book encourages you to discover a cuisine that Missourians have been eating up for more than two hundred years. Allow us to show you to your table.

Chapter 1

NATIVE BOUNTY AND THE COLONIAL TABLE

When baking bread, it helps to have good mud. Good mud mixed with the right amount of straw to build a mud oven. This was a common oven found throughout Missouri during the early colonial period, and it yielded the diet mainstay for the colonial French, Missouris first European settlers.

Bread was baked from flour milled from the wheat the colonists grewa product that complemented the natural abundance of foods that attracted not only the Europeans but also native inhabitants to migrate to what would become the state of Missouri.

Missouris abundant resources revolved around its ability to provide reliable food sources, which afforded food security for its settlements. These settlements included Missouris earliest residents, the moundbuilding Mississippians and Native American tribespeople who enjoyed a cornucopia of easily foraged, gathered and cultivated indigenous foods, supplemented by hunters who harvested a seemingly unlimited supply of game, birds and fish. These were proteins native cooks could roast, stew or dry for future use. These foods could be traded to neighboring tribes as well as French explorers/traders and colonialists who permanently settled along the Mississippis western shore and its connecting tributaries.

NATIVE FOODS TO COLONIAL FOODWAYS

Missouris woodlands were a hunter-gatherer paradise. Game, fish and forest delicacies such as black walnuts, persimmons, pawpaws and pecans were eaten. To enhance the food supply, beans, squash and corn were cultivated by the semi-nomadic Illini, Quapaw, Chickasaw and Oto tribes, as well as Missouris predominant tribes, the Missouria and Osage. These indigenous foods are best described as a frontier smorgasbord for the French colonists, who, by luck, stumbled on economic and culinary good fortune when they settled in one of the most fertile regions in the country.

This region is known as Upper Louisiana and the Illinois Countryan area whose rich soil and terroir produced the finest wheat, yielding bumper crops that, in turn, drove the establishment of lucrative milling operations that exported 300,000 pounds of flour to New Orleans in 1738 and 1739. This stone-ground whole wheat flour produced a dense bread that villagers reportedly ate nearly three pounds of per day; they were also used as edible trenchers.

Wheat, milled into flour, provided a valuable commodity that colonists traded for imported food staples and luxury items such as sugar, coffee and French winesa favorite for those weary of local wines made from native grapes and a welcomed addition to the table.

Another valuable export was bear meat and bear grease, the latter an essential for cooking and preservation. Gourmands of the day favored bear hams, extolling their superior taste over hams produced from locally raised hogs. This hot commodity unfortunately depleted Missouris black bear population. It would take more than two hundred years for the black bear to return to Missouri and regain numbers to a level where the Missouri Department of Conservation would approve limited bear hunting.

Missouri buffalo and elk suffered fates similar to the black bear. Their numbers also dwindled; the buffalo were pushed beyond their Missouri range, and elk were completely wiped out. Another delicacy that suffered from overharvesting was the pelican, once abundantly found along the river. This tasty bird, like the black bear, has also reestablished itself along the upper Mississippi River. Luckily, quail, prairie hen, partridge, crane, duck, geese, wild pigeon, grouse and doves remained in fairly good supply. However, when needed, to supplement the food supply Shawnee hunters provided deer and turkey to the settlements.