Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2019 by Akila Sankar McConnell

All rights reserved

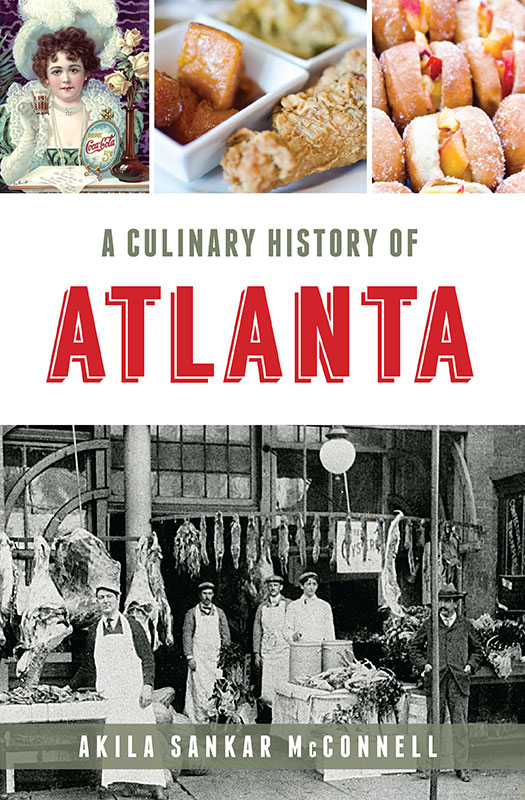

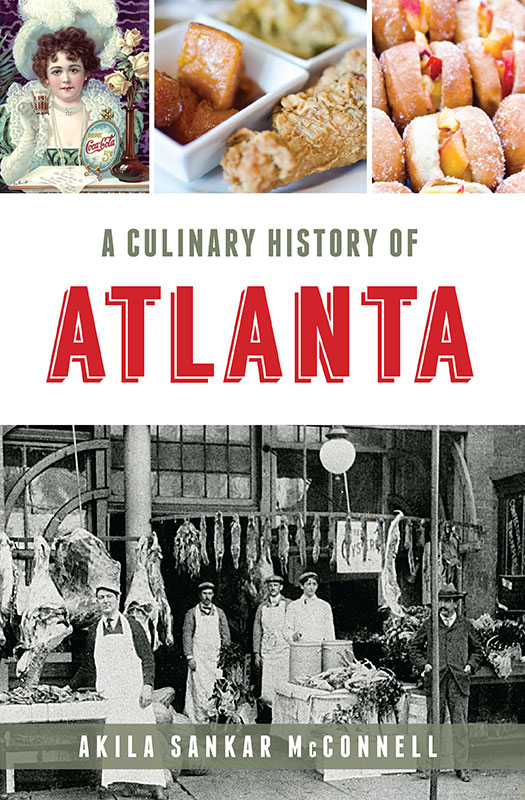

Front cover, top, left to right: Early Coca-Cola advertisement, approximately 1890s. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; Paschals fried chicken, yams and cornbread dressing. Author photo; Peach slider donuts from Revolution Doughnuts. Author photo. Front cover, bottom: Atlanta Market Co., circa 1900. Atlanta History Photograph Collection, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center.

First published 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.686.9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019932532

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.123.9

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

THE VILLAGE BY THE PEACH TREE

PRE-COLONIZATION

Long ago, before time was measured by calendars and clocks, the Muskogee (Creek) Indians marked a peach tree next to the Chattahoochee River as a convenient meeting place. A network of trails soon made its way to that tree, and uncounted Muskogee women picked fuzzy pink-orange fruit as sticky juice dripped down their childrens chins and hands.

Eventually, the Muskogee built a village there named Pakanahuili, literally Standing Peachtree, referring to that large peach tree that stood at the top of the hill. The Muskogee comprised the largest Native American nation in the state of Georgia, controlling much of present-day Georgia and Alabama, but it was not a single tribe. Rather, the Muskogee were a confederacy or commonwealth of chiefdoms, with each chiefdom consisting of eight to ten villages and around five thousand people who adopted sophisticated agricultural methods, rituals, art and architecture, managed by a single chief. Standing Peachtree was the main village in its chiefdom.

For ten thousand years, the success and strength of the Muskogee Nation lay in its domination of food. Food was critical to the Muskogee way of life, and the Creek women were inventive and talented cooks, to the point that every European visitor who wrote about them mentioned the variety, flavor and freshness of Creek cuisine in their writings.

Benjamin Hawkins, George Washingtons principal Indian agent in the Southeast, was continually delighted by the delicious food he ate among the Georgia Muskogee. At one Creek village in 1796, Hawkins noted that the women grew beans, ground peas, squash, watermelons, collards and onions and raised hogs, cattle and poultry. The Muskogee wanted principally salt, that they used but little from necessity, and where they were able to supply themselves plentifully with meat, they were unable to preserve it for the want of salt. For dinner, a Muskogee chief greeted Hawkins with good bread, pork and potatoes, ground peas and dried peaches, and in the morning, he breakfasted on corn cakes and pork. The Indians he visited had fowl, hogs and cattle and a four-acre field fenced for corn and potatoes.

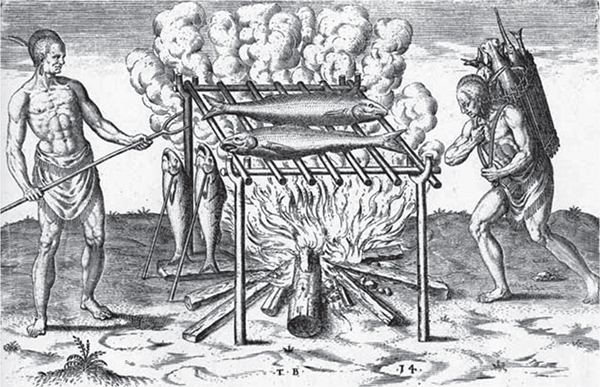

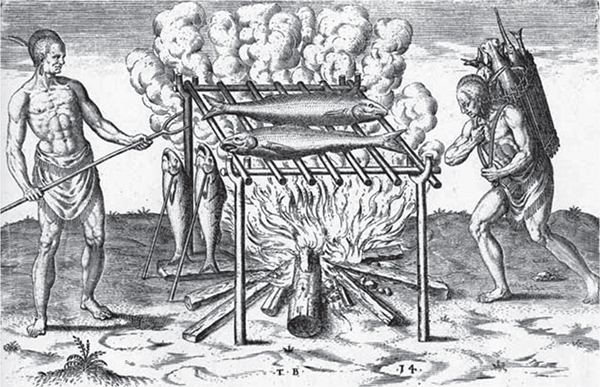

Among the Native American tribes, the Muskogee Nation was particularly adept at agriculture, with women planting and gathering, while the men focused on hunting and fishing. The women dried and preserved fruits, vegetables and meat and boiled, roasted and smoked meat and fish. Barbecuesmoking meats on thin slats of woodwas the most popular Muskogee method of cooking. Any type of meat could be intended for the barbecue, ranging from alligator and fish along the coast to venison in the verdant woods near Standing Peachtree. Hawkins reported that a deer hunted and killed would be butchered and on the barbecue in less than three hours.

Early barbecue with Secota Indians. Thomas Hariot, 1585, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (2003).

Timucua men and women cultivating a field. Theodor de Bry, engraver, Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, 1591, Library of Congress.

But corn was the Muskogee Nations most important food. Domesticated, bred and adapted from a grass called teosinte near the Tehuacan Valley of Mexico more than five thousand years ago, corn quickly became the predominant food across the Americas. In the southeastern United States, corn accounted for 50 percent of the Muskogee diet, and hominy was the preferred way to prepare corn. The Muskogee particularly favored sofkee, an invigorating morning drink of thin hominy flavored with venison. When Benjamin Hawkins came to Georgia, one village chief presented him with a basket of corn for his horses, a fowl, sofkee and hominy.

Given the importance of food, every month, the Muskogee held a festival dedicated to the first fruits of horticulture and hunting, such as the gathering of chestnuts, mulberries and blackberries. Of these festivals, none was more important than the poskita, or Busk, to recognize the importance of the ripening of the green corn. Held each year in July or August, depending on when the corn began to ripen, the Busk celebrated collective renewal, including rites of purification such as fasting, the destruction of old things and mass cleaning and refurbishing. Then, a priest would ignite a new fire in which young men would burn an ear of the seasons first corn, recognizing that corn was a sacred plant that gave life to the chiefdom.

BY THE TIME THE white man reached the state of Georgia in the late 1700s, Standing Peachtree, that small village by the Chattahoochee, had become a notable trading post and rendezvous point due to its strategic position on the frontier between the competing Muskogee and Cherokee Nations. In the first written mention of the village in 1782, a Georgia colonel begged a South Carolina general to send troops to help him battle a group of braves who were meeting at the standing Peach Tree. In August of that year, a commissioner planned to meet with Indians at the standing peach tree.

During the War of 1812, the Creek Nation split into two. Half of the Creek Nation supported the British because they feared that the Americans would continue expanding into Indian lands. The other half of the Creek Nation supported the Americans, believing that the Americans would maintain good relations with them, become good trading partners and help them prosper. The Creek Indians who lived at Standing Peachtree were among those who supported the Americans.

As a friendly village to the fledgling American government, Standing Peachtree was chosen as the site of a U.S. infantry fort, unoriginally named Fort Peachtree. Built directly across the river from the Standing Peachtree village, Fort Peachtree was led by Lieutenant George Rockingham Gilmer, and the militia named the road running from Fort Peachtree to Fort Daniel as Peachtree Road.

Next page