A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications 2013

Copyright Katharine Quarmby 2013

The moral right of Katharine Quarmby to be identified as the Author of this work as been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

Extract from Reservations by Charles Smith on p. 251 reprinted with the permission of Essex County Council.

Lyrics from The Terror Time on p. 51 by Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger reprinted with the permission of Stormking Music/Bicycle Music. All rights reserved.

reprinted with the permission of David Morley.

reprinted with the permission of the poet.

ISBN 978-1-85168-949-1

eBook ISBN 978-1-78074-106-2

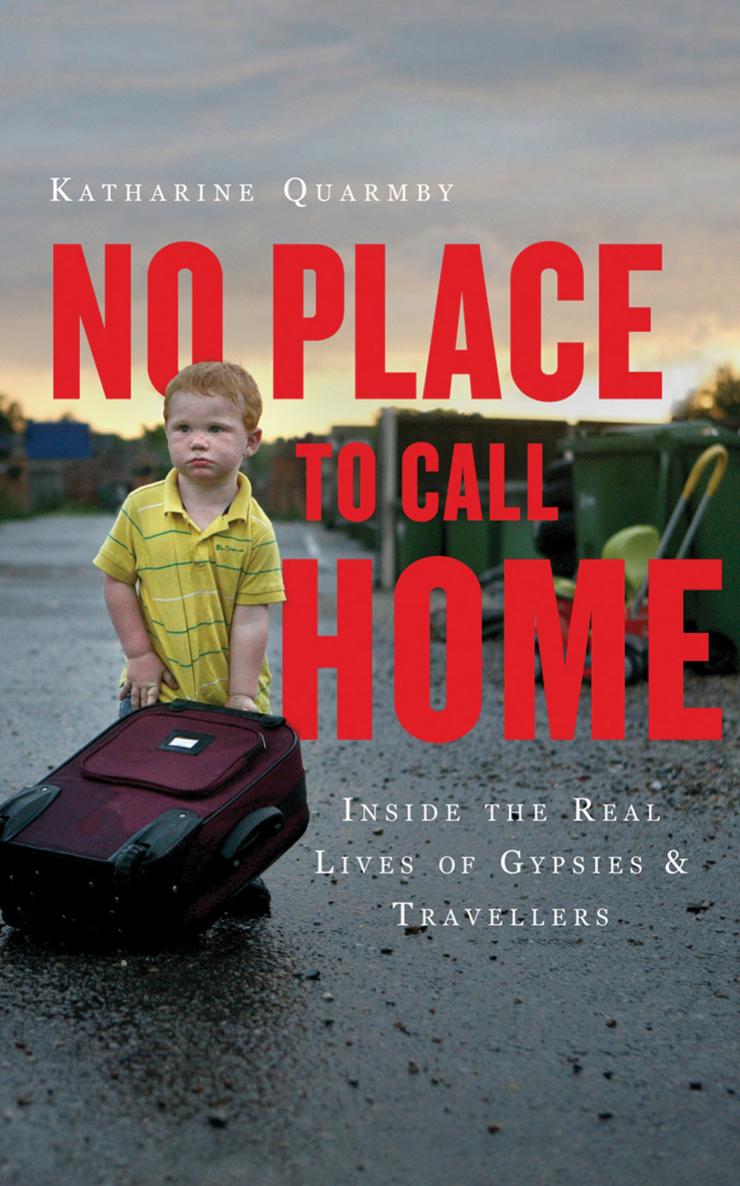

Cover design by Rawshock

Typesetting and eBook by Tetragon, London

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street, London, WC1B 3SR

United Kingdom

Prologue

I drove out to Dale Farm on the morning of Wednesday, 19 October 2011, with a sick feeling in my stomach. This, at last, was eviction day for some eighty or so Irish Traveller families, after ten long years of wrangling. There were to be no more phoney wars.

The McCarthys, the Sheridans, the Flynns, the OBriens and the Slatterys, among others, some of whom Id first met more than five years earlier, were going to leave their beloved home, Dale Farm, with its scruffy dogs and bumpy tracks, its immaculate gated pitches and tidy caravans and chalets. Back in 2006, there had been little to no press interest in the site, and I had to persuade my editor at The Economist that this was a story worth covering. She gave me 850 words.

Now, I had to park at a garden centre a long walk down the lane because there was no room nearer to the site. The world media were there from Japan, the US, Canada and mainland Europe. I noticed that the air smelt foul. Three helicopters hovered overhead as a plume of smoke drifted upwards from a burning caravan. A few masked protestors shouted obscenities at the police. Many of the Travellers were close to tears, although a few remained defiant. Eviction day was underway.

Mary Ann McCarthy had left the site a few weeks earlier. Grattan Puxon was holed up inside the embattled encampment and wasnt answering his phone. Finally, two legal observers smuggled me in.

I walked round to the back, where the police and bailiffs had breached the defences at 7 a.m. I almost immediately ran into Michelle and Nora Sheridan, who were both near tears. Nora told me: I saw someone being tasered: he fizzed, I tell you, as she tried to stop her three boys from going near the police lines. Michelle added: Yes, some of them were throwing stones but it was inhumane. I was running away with a child in my arms. I was terrified. Tom, her youngest, who was just eighteen months old, was crying in her arms. Nearby I saw Candy Sheridan, the vice-chairwoman of the Gypsy Council, negotiating with the Bronze Commander to get an ambulance on to the site to evacuate two sick residents.

I looked around at this site that I had visited so many times over the past years. The caravan was still burning, and activists scurried around with little rhyme or reason. A community was being dismantled, real people were losing the only home theyd ever had, yet the scene was unreal, like seeing agit-prop theatre in the round. Dale Farm was a paradox an iconic symbol of the struggle of nomadic people to find a place to call home yet in so many ways completely different from life for most Romani Gypsy and Traveller families in the UK. What, in the end, did the battle of Dale Farm signify, and how did it connect to the wider story of the nomads in our midst, and the settled communitys relationship with them? What was this fight really about?

Katharine Quarmby

Introduction

This book is about some of the last nomadic communities in the UK called by many names, but generically known to most people as Gypsies, a contested word that includes, in fact, many separate communities. They include the English and Scotch Romanies, the Welsh Kale Romanies, the Irish Travellers, the British Showpeople and (New) Travellers, as well as their own offshoots, including the Horsedrawns and the Boaters. What unites all of them is their struggle to survive, make homes and hold fast to cultures that often bring them into conflict with the so-called settled community.

I knew, from the moment that I was commissioned to write a book about Britains nomadic peoples in the wake of the eviction from Dale Farm, that I had to go much further afield to set that particular location in its rightful context as merely one part of a long and bitter struggle for Traveller sites in this country. Dale Farm was and remains highly significant, but I wanted to visit other trouble spots and interview other nomads English and Scottish Romani Gypsies and Travellers, and even some of the newly arrived Roma, whose voices also should be heard.

This book, therefore, has its roots in Dale Farm, the first Traveller community I ever visited and of its inhabitants. But it is also the story of another site, Meriden, occupied, like Dale Farm, without planning permission, by Romani Gypsies with roots in Scotland, Wales and England. I also travelled to Glasgow, to interview Slovakian Roma, who had arrived rapidly over a few years, and agencies working with them, and travelled to both the Stow and the Appleby horse fairs to visit Gypsies and Travellers in trading and holiday mode. I went to Darlington in the North-East to visit the much respected sherar rom , elder Billy Welch, who organises Appleby Fair and has big dreams about getting out the Gypsy and Traveller vote, and to the North-West to talk to the devastated family of Johnny Delaney, a teenager from an Irish Traveller background who was kicked to death for being a Gypsy ten years ago. I travelled down to Bristol to talk to veteran New Traveller Tony Thomson about life on the road in the 1980s, and being caught up the vicious policies of the Conservative government at that time. I also journeyed into East Anglia, where New Travellers, Irish Travellers and English Gypsies have made homes, and north of London, to Luton, to meet some of the destitute Romanian Roma who have created a vibrant community in the heart of England with the help of an inspirational Church of England priest named Martin Burrell. I was also invited to a convention in North Yorkshire by the Gypsy evangelical church, Light and Life, which is growing at an exponential rate and whose influence on nomadic cultures in the UK cannot be underestimated.

I could have travelled more to Rathkeale, where EnglishIrish Travellers go for weddings, funerals and to have the graves of their dear dead blessed once a year, or to Central and Eastern Europe, where most of the worlds Roma population (and the smaller population of Sinti and other nomadic groups) live. But I chose to concentrate on the experience of Gypsies, Roma and Travellers living in the UK to go deep, rather than wide. But it was striking that many of those I interviewed would phone me from abroad, or from hundreds of miles away from their actual home, completely comfortable having travelled miles to find work as long as they were with family or were earning money to keep their family.