A Dream Foreclosed

BLACK AMERICA AND THE FIGHT FOR A PLACE TO CALL HOME

Laura Gottesdiener

Foreword by Clarence Lusane

ZUCCOTTI PARK PRESS

Copyright 2013 by Laura Gottesdiener

Foreword 2013 by Clarence Lusane

All Rights Reserved.

This publication is a joint project of Adelante Alliance,

Essential Information and Zuccotti Park Press.

Cover design by POLLEN.

Cover image by Brent Lewis. See caption on page 152

ISBN: 978-1-884519-22-2

Zuccotti Park Press

PO Box 2726

Westfield, New Jersey 07027 USA

www.zuccottiparkpress.com

occupy@adelantealliance.org

Dedicated to my parents, Debbie Novick and Larry Gottesdiener, who gave me the best home that a child could ever have.

Contents

by Clarence Lusane

by Jajuanna Walker

A Dream Deferred

by Langston Hughes

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

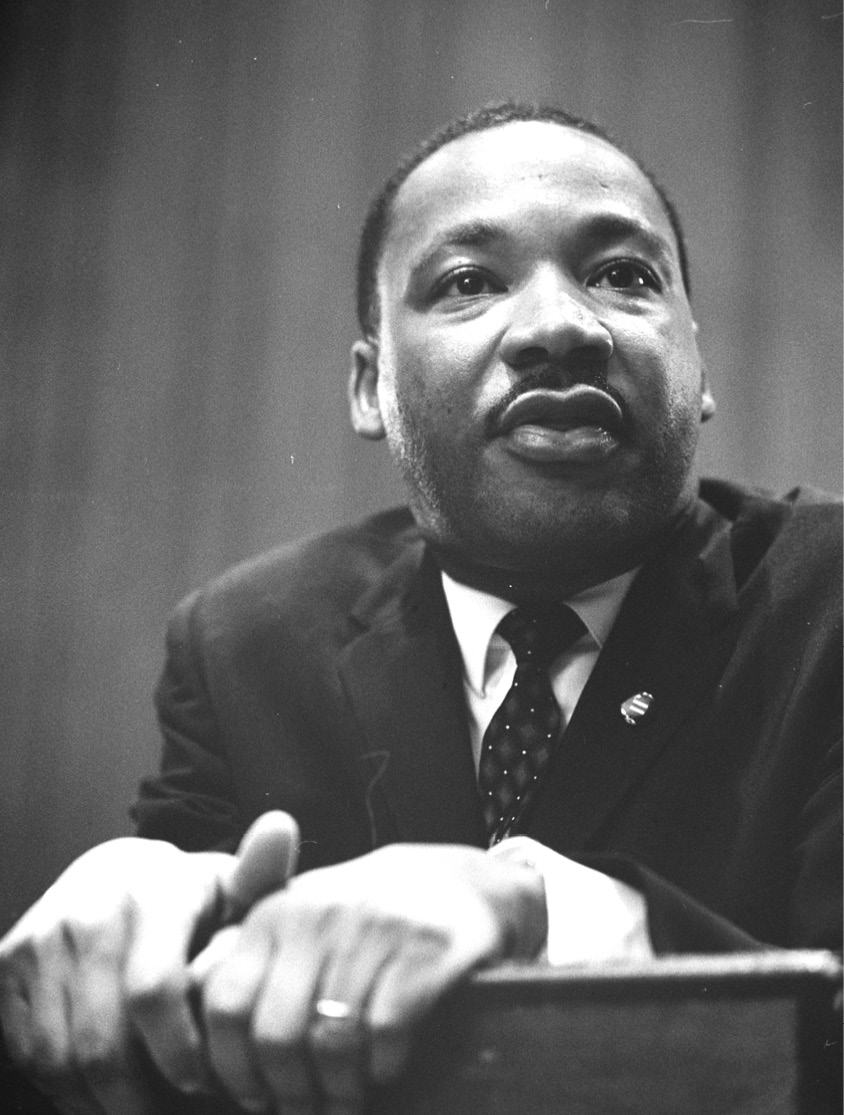

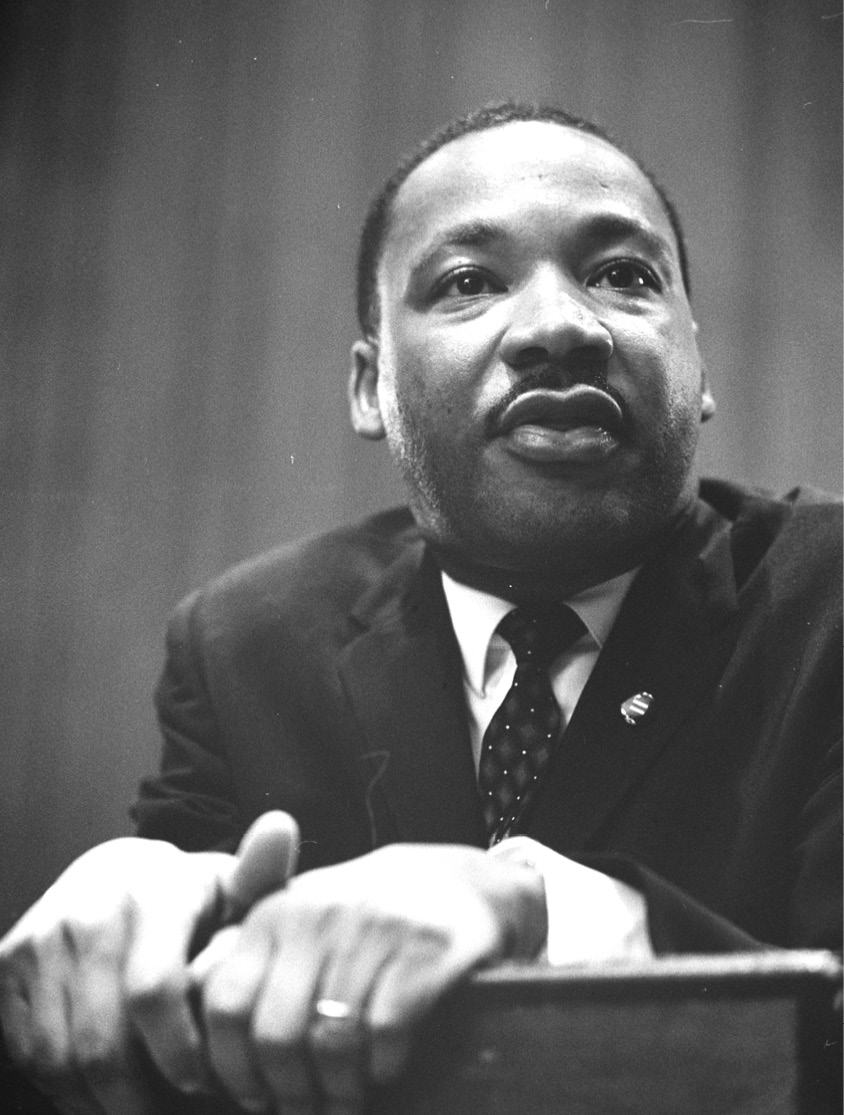

Martin Luther King Jr., March 26, 1964. Photo by Marion S. Trikosko. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Foreword

by Clarence Lusane

Just as the doctrine of white supremacy came into being to justify the profitable system of slavery, through shrewd and subtle ways some realtors perpetuate the same racist doctrine to justify the profitable real estate business.

REV. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.

Rev. Martin Luther King, at the time of his assassination, was on the front lines of the fight for workers in Memphis and in the process of launching a nationwide poor peoples campaign. Few recall that exactly one week after his murder, on April 11, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Fair Housing Act. The Act outlaws discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of dwellings, and in other housing-related transactions, based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, or disability. This law, Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, honored the Herculean struggle waged by King for two years to highlight the issue of housing segregation and discrimination.

In 1965, King brought the civil rights movement to the North and took on the issue of open housing in Chicago and its suburbs. At the time, Chicago was the second-largest city in the United States, and its systems of education, employment, and housing were as segregated as any in the deep South. King hoped to release what he called an army of nonviolent protesters that would challenge these conditions and bring about fundamental change. However, he hit a solid wall of whiteand often violentopposition that involved elected officials, law enforcement authorities, bankers, real estate agents, lawyers, and ordinary citizens. As a result, legislation was stalled in Congress until the political opening caused by Kings murderand the widespread riots that followedallowed Johnson to push the bill through in only a week.

Today, we see a more dressed-up but similar rogues coalition, which, rather than prevent black homeownership, has figured out a way to exploit it. Instead of bottles and bricks thrown at protesters and marchers, the weapons of choice have been usurious mortgage contracts and signing pens. The language of segregation and interposition has been replaced with false narratives of getting a piece of the American pie and property ownership as freedom. The evil of states rights has given way to the perniciousness of bankers rights. For many families in the black community, home mortgages became new shackles, ending dreams and futures.

As Laura Gottesdiener documents in her brilliant discourse on the battle over home and community by African Americans, housing has always been integral to the fight for racial equality and justice. In a humane and somber voice, she captures the brutality of how those working in the political, real estate, banking, and financial sectors coordinate and collude to garner superprofits irrespective of the mass destruction caused to millions of individual mortgage holders or the nations economic security as a whole. So egregious have their practices been that they triggered massive national and international losses, bringing global economies to the brink of collapse. This criminal enterprise, for which not a single banker or official in the financial or banking industry has yet to be prosecuted or imprisoned, has forced millions of American families out of their homes and into the streets. African American and Latino homeowners, in particular, have paid dearly, as they were disproportionately targeted and victimized by the predatory schemes and con games enacted by those devoid of any sense of national community or conscience.

As far back as 2006, the Center for Responsible Lending was already wary of the subprime loans targeting the black community. The Center predicted that unless the government intervened, it was likely that bankers would directly cause the largest loss of African-American wealth that we have ever seen, wiping out a generation of home wealth building.

Gottesdiener exposes how very deliberate, shocking strategies to target the black community were implemented. Black churches, rather than white ones, were seen as sites to heavily promote and market toxic loans. Real estate agents were given bonuses if they could convince black clients, regardless of their ability to carry the terms of the loan, to take the higher-cost, higher-risk deals. Shameless racism and financial predation were the order of the day throughout the entire home-financing industry.

The housing devastation experienced by the black community in the last few years is but one outrage in a context of unyielding economic turmoil. Many scholars and economists have lamented the disparate impact of the recession on black and Latino communities. As Dollars & Sense magazine noted, The Great Recession produced the largest setback in racial wealth equality in the United States over the last quarter century.

But the crisis that has eviscerated African American homeowners and potential homeowners is about much more than just profits and rapacious greed. Fundamentally, the battle is over community. For many African Americans, owning a home is about building a community and maintaining the stability that allow for active participation in ones neighborhood and in society more generally. The goal of owning a home has never been simply a pie-in-the-sky or abstract notion of the American Dream. It has been an indicator of individual achievement but also a collective accomplishment embedded in the struggle for racial equality, justice, and solidarity.

The four families profiled by Gottesdiener speak over and over again about their fear of losing community roots, an anxiety in some ways more terrifying than just the physical or economic loses they face. Detroits Bertha Garrett speaks for them and many more when she states, Memory lives in a space. This is what people dont understand. We raised our kids here. Its more than just an investment. To uproot a people is to uproot their culture, social networks, economic ties, and even spiritual bonds. The stories told by Garrett, Griggs Wimbley, Michael Hutchins, Martha Biggs, and too many others echo the narratives of refugees around the world who have been forced to search for a new home, new roots, new social and personal connections. In the lingua franca of the United Nations, the economic storm that swept the nation generated a humanitarian crisis consisting of millions of people internally displaced by foreclosure and eviction.

Next page