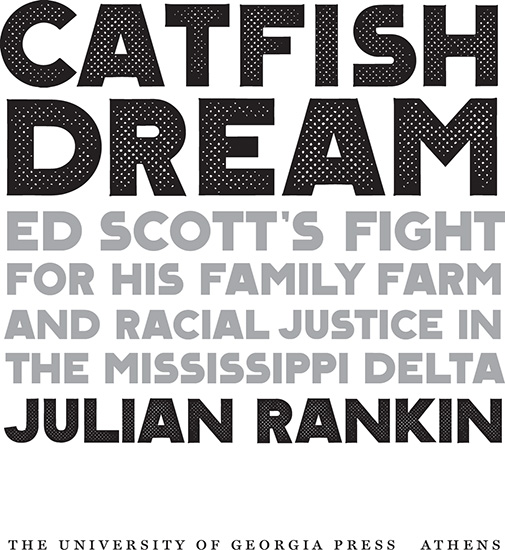

CATFISH DREAM

Southern Foodways Alliance

Studies in Culture, People, and Place

The series explores key themes and tensions in food studies including race, class, gender, power, and the environmenton a macroscale and also through the microstories of men and women who grow, prepare, and serve food. It presents a variety of voices, from scholars to journalists to writers of creative nonfiction.

Series Editor

John T. Edge

SERIES ADVISORY BOARD

Brett Anderson | New Orleans Times-Picayune

Elizabeth Engelhardt | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Psyche Williams-Forson | University of Maryland at College Park

A Sarah Mills Hodge Fund Publication

This publication is made possible in part through a grant from the Hodge Foundation in memory of its founder, Sarah Mills Hodge, who devoted her life to the relief and education of African Americans in Savannah, Georgia.

2018 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Designed by Erin Kirk New

Set in 10/15 Miller Text with Tarno display

Most University of Georgia Press titles are available from popular e-book vendors.

Printed digitally

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018937821

ISBN: 9780820353609 (hardback)

ISBN: 9780820353593 (paperback)

ISBN: 9780820353616 (e-book)

For Caroline and little Julian, for the Scotts,

and for families everywhere who endure, tell stories, and

give their children the gifts of legacy and namesake

The catfish didnt miss the current. Theyd never known it. They lapped the pond all day like pace cars. At feeding time, they thrashed for their share of pellets. The farmers bred them for size and taste and texture and profit. They swam around in that little man-made lake and waited for the chopping block and the flash-frozen package. Their bodies were bullion. There were others of them, wild ones, who lived in the open waters of the river to the west. They sometimes got caught on the trotlines of grizzled river rats. Mostly they grew big as they pleased and swam deep into the crevices of the underwater earth. Fishermen told stories. He had whiskers big as bullwhips. Men saw fleeting visions of this barnacled ghost ship. If you caught him and ate him, they said, youd gain all the wisdom of a century. He was part whale. Too big for the line. You could tell it was he by the waves he made when he breached the surface.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Babe Ruth wasnt born a sultan (of swat) or a king (of swing). He grew up an unruly and unsupervised Baltimore youth, and a Catholic brother named Matthias molded him into rawhide-slugging form. I learned this in first grade. Before, I had been certain that all people who did great things had always been great. But George Washington the man wasnt carved out of marble. There was a time when he didnt tower over folks, when his hairdo wasnt powdered, when he was one of us.

In Mississippi Delta history, farmer Edward Logan Scott Jr. is legend. During his lifetime, many thought of him as mythic; others, pure myth. I sat with him for hours of sprawling conversation. From his wheelchair in a dimly lit living room he recounted his history. The Scott family opened their archives to me and shared the story of Scotts father, Edward Sr., who brought the family to Mississippi in the 1920s. Edward Sr. left his job in Alabama as a postman and farmer to find more prosperous conditions. Ed Scott Jr., born in 1922, lived into his fathers pioneering history and built upon it. When he dug up 160 acres of arable farmland and turned them into catfish ponds in 1981, gossip and folktale made it sound like black magic. If it is magic, it cant be duplicated. But if exceptionalism is man-made, then it can be made again.

I learned to write a book by writing this book. When I hit roadblocks, I looked to my interviews with Scott for guidance. I applied his philosophies about catfish and activism. The first draft was digging the ponds. And then stocking. And feeding. And so on. The intimidating scope of a first bookline after line, page after page, season after seasonencompassed infinite fields of rice and beans too giant to conceptualize until, one pass at a time up and down the furrows like a farmer, it wasnt any longer. I came to see my own brief Mississippi Delta childhood in concert with Scotts story. I was a toddler playing down by the cotton gin in Shaw in 1989 when Scott was a half hour away in Leflore County battling the government to keep his farm afloat.

When I lived in the Delta as a boy, every little thing that happened had shades of life and death, and nothing that happened in the wider world shook my immediate existence. I trusted only what was in my vision or grasp. I loved a cat named Rupert, who roamed at night on the hunt for mice across the street at the old cotton gin. One day we found Rupert dead in the driveway. My mother put him in a black garbage bag, and we buried him in the yard below a little molehill two feet high. My mother told me it was the highest point in the Delta, and I believed her.

Stories like Ed Scotts are not only Mississippi and southern tales, but American ones. Their characters contend with both human and nature, from the prejudice of their neighbors and the collateral consequences of political ambitions to failing infrastructure and the wrath of the drought and flood. When most of his peers farmed 40-, 80-, or 120-acre plots, Scott farmed thousands. He had the entrepreneurial savvy of a railroad baron. To borrow from a well-known contemporary poet, put Scott anywhere on Gods green earth and hed triple his worth. His accomplishments flowed out to and benefitted others, primarily the surrounding Delta communities of black farmers and families. In its totality, Scotts life serves up questions about who we ought to beas a collective nation in service to our diversity of citizens, and as citizens striving for our perfect parcel of the American dream.

I knew Ed Scott for only a short time. I do not know his every secret. But when he unfurled his story before me, it had his soul in it. I met Scott in his dwindling sunset. I followed him backward through time. Layers of the man, the soldier, the boy. Not just old. Not only young. Scott the agelessa man for all ages. A man who should be remembered.

PART I SEED

1 FAMILY LAND

An American flag, sun-bleached, hung motionless from its pole on the front of the farmhouse. The air was humid. Thick like paraffin. The sky was clear, but Ed Scott Jr., seated behind an aluminum desk in his office, sensed gathering clouds. More thunder. And fire.

He reclined in a wooden chair, in a button-up shirt that read Scotts Fresh Catfish tucked into jeans. Scotts eyes darted. He inspected the familiar room and reviewed a mental checklist. Invoices peeped out of folders. More dust floated in the air, caught in the light, than he would prefer. Things needed doing. His belly hung slightly over his belt. He was a well-fed sixty-seven. He wore a farm cap on his head, and a mustache bristled above his upper lip. It was 1989.

Scott had bought the desk and the filing cabinets and everything else from an industrial office supply manufacturer. Thousands of other offices in a hundred other American industries probably had the same functional suite. Everything but the chair. Scott had been more particular about his swiveling desk chair. It needed a cushion, stature, and durability. Like Red Wing boots or a John Deere Model A tractor, whose own captains seat Scott considered the paragon. Things of quality like the chair need only be acquired once, Scott believed. They should last forever. Like family land.