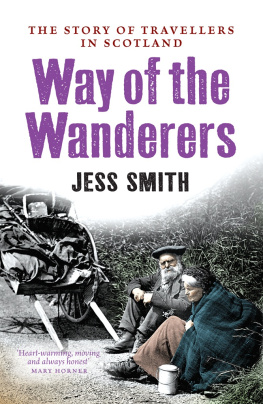

W AY OF THE W ANDERERS

J ESS S MITH

was raised in a large family of Scottish Travellers. She left her old ways behind when she married her husband Dave, a non-Traveller. Her writing career did not begin until her three children left home to build their own nests. It was then she took the decision to write about her culture. Jessies Journey was the first book in her autobiographical trilogy, which continued with Tales from the Tent and concluded with Tears for a Tinker. She has also written a novel, Bruars Rest, and a collection of stories for young readers, Sookin Berries. Jess is a gifted storyteller and has shared her tales in live performances throughout Britain, Ireland and Australia.

First published in 2012 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Jess Smith 2012

The author gratefully acknowledges the Estate of Athole Cameron for The Gaun-Aboot Bairn; Mamie Carson for Keith McPhersons The Muckle Stane; Robert Dawson for quotations from Empty Lands and unpublished documents; Mary McKay for A Life Long Gone; Andrew Sinclair for the quotations from Rosslyn: The Story of Rosslyn Chapel and the True Story Behind the Da Vinci Code; and Sheila Stewart for Belle Stewarts The Berryfields o Blair and Glen Isla.

The moral right of Jess Smith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78027 078 4

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 565 9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Set in Bembo and Adobe Jenson at Birlinn

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

I LLUSTRATIONS

A CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To my dear friend Anne for all her work and friendship.

To Robert Dawson, for uncovering the plight of the Scottish Travellers in the nineteenth century through the 1895 report for the then Secretary of State for Scotland on the Vagrants, Itinerants, Beggars and Inebriates of Scotland.

To Jim Caird for providing A History, or Notes upon the Family of Caird, plus the Clan from Very Early Times by Rennie Alexander Caird (1915).

To The National Archives of Scotland for Educating of Scottish Tinkers and Vagrants.

To the A.K.Bell library for copies of the Aldour Tinker School log book and letters.

To Seamus Macphee for allowing me to ransack his collected papers on the Perth and Kinross housing experiment for Tinkers.

To the Orkney archives.

To Sheila Stewart MBE and to Donald, John, George and Alistair for their sharing of family stories and filling blanks in the narrative.

To Belle Stewart BEM.

To Mary Mackay for her information on Irish Pavee (Irish Travellers).

To Mary Hendry for allowing me access to her prized collection of Andrew McCormacks Gypsy and Tinkler books.

To David Cowan for his expert advice on standing stones and to Colin Mayall who helped me understand a little of the Pictish and Roman history.

To Macainsh Brown for transporting me back in time to the day of a powerful battle over illicit stills.

When I was researching and compiling this book a sea of souls closed ranks to help me make sense of a huge quantity of material. I want to shout out their names from a high point, but they wish for no recognition. You know who you are, so from my heart a million thanks.

I dedicate this book to the ancestors of the Travelling People

T HE I NSPIRATION

There can be no greater enjoyment to the inquisitive mind than to find light where there was till then darkness.

From William Forbes Skene, The Highlanders of Scotland

I t was early 1982 and there we were: him at deaths door and me crying my eyes out over the linen-sheeted bed, watching his life ebbing away. Gripped by the sheer helplessness of knowing that at any moment his sun would dip for the final time, I made him a silent promise: to discover as much information about the Scottish Travellers as it was possible to find, and to write a book, a simple, easy-to-read book.

Yet, walking away from the hospital as the linen sheet was being pulled across his face I knew there was no way I could write as much as a goodbye note, let alone a book, in memory of that good man, my father, Charles Riley. I had no proper education apart from the usual basics. Our family were travellers of the road, and we would leave school in April, re-entering the classroom in October. Our ways were travelling and had always been so.

Twenty years went by and my own family had flown their nests. Totally convinced that writing a book was far beyond my abilities, Id decided instead to go where I could feel the breath of my ancestors and walk in their hardy footsteps, traversing Scotlands remote paths and climbing her formidable mountains. I found peace and happiness in the sky above and the rock beneath, and I wished nothing better for the future.

But life is an unpredictable mistress, guided by blind circumstance. My father had a favourite saying: Whats before you will not go by you. He wasnt a religious man, and he allowed fate to guide him. I believe that is exactly how this book has come about, because in the summer of 2000 fate began to map out a new path for me.

I had just traversed across Buachaille Etive Mor and the neighbouring peaks of Glen Coe, the mountains glowing red and brown with autumn hues. It had been one of those days that all hill-walkers and mountaineers experience at some time: next to perfect, just enough warmth of sunshine on the climb and the bluest clarity all round on the summit where the eye can see for miles.

As I trudged back to the car park I was suddenly aware of something missing; there was a haunting silence. Why was there no busking piper? Standing on a narrow strip of tarmac in Macdonalds glen I strained my ears for that familiar sound, a sound that had always been part of me and my past. Where was the piper resplendent in full Highland regalia the towering giant, Wullie MacPhee, or John Macdonald, the auld weaver, or those stirring masters of the bagpipe, the Stewart boys?

The tourists who flocked to the Pass of Glencoe would eagerly take photographs of the Scottish piper, surrounded by the glens and mountains of their forebears, the heartland of the Diaspora, to display proudly back home. To many this moment was the highlight of their Scottish tour. At Edinburgh Castle pipers resplendent in their tartan kilts made excellent subjects for a camera lens, but they were nothing in comparison to a lone piper, his face brooding on the past, with the haunting shape of the Aonach Eagath ridge on his right and the Lost Valley on his left, the deep notes stirring the ghosts of Macdonalds children massacred centuries ago by those who ruled Scotland.

Standing in the vacant circle of silence, legs weary with the days climbing, my heart ached. I was mourning the loss of those giants of Traveller culture who piped through thunderstorms and fierce gales. They did it because they needed their summer busking money; without it theyd see a lean winter, but it was more than that, much more. Piping at the Pass was a way of honouring those Macdonald clansmen.