Dr. Seuss

introduction

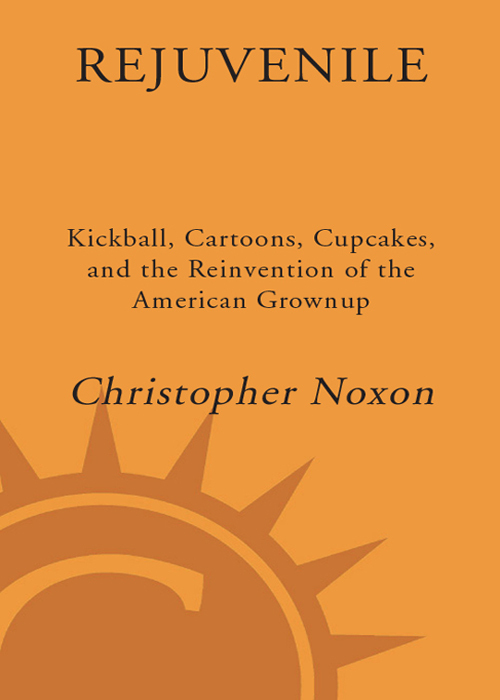

ONCE UPON A TIME, boys and girls grew up, set out on their own, and, somewhere along the way, matured. They got serious. They set aside childish things.

Or so the story goes. Today, the process of maturity is rarely so straightforward. To be sure, many people pass the usual milestones and comfortably take their place as respectable, responsible adults. But such upstanding citizens are getting lonelier all the time. Most of us reach adulthood feeling entirely out of sync with what sociologists call age norms. And a few of us are waging all-out assaults against long-standing notions of young and old, mature and immature, novice and pro.

Captains of industry now appear on the cover of Business Week with Super Soaker water pistols and Sea-Monkey executive sets. College students with lunchbox purses and Muppet berets walk arm-and-arm with moms sporting rock star tattoos and sparkly T-shirts poached from the Junior Miss section. Middle-aged professionals download pop song ringtones and punctuate correspondence with language swiped straight from the schoolyard. (You da man! says the insurance adjuster. Duh! agrees the building inspector.) Crowds flock to Las Vegas to catch Cirque du Soleils latest extravaganza, watch pirates clash sabers in front of Treasure Island hotel, or hop on one of several casino roller coasters. Twentysomething nightclubbers in London wear school uniforms and dance to songs they dimly remember from their teen years, then finish the night with cupcakes and bowls of macaroni and cheese. In Manhattan crowds cram bars for all-adult spelling bees or drop $100 for tickets to Avenue Q, a show about maxed-out credit cards and career disappointments performed by googly-eyed puppets. Senior citizens team up for extreme-sports excursions and Disney World vacations.

Its hard to imagine adults in previous eras so unashamedly indulging their inner children. But these are not the adults of twenty years ago. They constitute a new breed of adult, identified by a determination to remain playful, energetic, and flexible in the face of adult responsibilities. Whether buying cars marketed to consumers half their age, dressing in baby-doll fashions, or bonding over games like Twister or stickball, this new band of grown-ups refuses to give up things they never stopped loving, or revels in things they were denied or never got around to as children. Most have busy lives and adult responsibilities. Many have children of their own. They are not stunted adolescents. They are something new: rejuveniles.

Evidence of the presence and influence of rejuveniles is all around. The Cartoon Network boasts bigger overall ratings among viewers aged eighteen to thirty-four than CNN, Fox News, or any cable news channel. Half of the visitors to Disney World are childless adults, making the Magic Kingdom the number-one adult vacation destination in the world. Department stores stock fuzzy pajamas with attached feet in adult sizes. The website Classmates.com reports that 60 million people have signed up to reunite with long-lost school pals. (Theres something about signing on to Classmates.com that makes you feel sixteen again, reported 60 Minutes.) The Entertainment Software Association reports that the average age of video game players is twenty-nine, up from eighteen in 1990. Hello Kittys mouthless cartoon face now graces toasters, taxicabs, and vibrators.

Such pop culture ephemera reflect seismic social change. Adults are now putting off marriage longer than ever (the average age of women at their first marriage was 25.3 in 2003, a historic high; for men it was 26.9); they are waiting longer to become parents (middle and upper classes are deferring childbirth ten to twenty years later than their parents); and living with their parents far longer than ever (38 percent of single adults aged twenty to thirty-four live with their parents). Meanwhile, the few remaining rites of passage that historically set adults on a new course in life are fading or losing their meaning altogether. For some, this erosion of clear boundaries has created confusion and uncertainty. But for rejuveniles, it means a sudden lifting of sanctions that would otherwise discourage a sudden impulse to collect Japanese manga, indulge a love of Scooby-Doo, or develop a Necco Wafer habit.

This book describes the new breed of adult and explains the rejuveniles role in shaping and reflecting our age. I identify the demographic forces that fostered the rejuvenile, survey the pastimes rejuveniles have built their lives around, and look back at a remarkably similar outbreak of kidcentric enthusiasm one hundred years ago. I talk with adults who live with their parents, parents determined to reexperience childhood via their offspring, and grown-ups who dress and play and party like they did in high school. And I take a hard look at Walt Disney, the most influential rejuvenile of the twentieth century, the person most responsible for the blurring of adult and child sensibilities. By loitering in a territory established as the exclusive dominion of children, rejuveniles are challenging a rarely examined assumption: that ones age should dictate ones activities, social group, and mind-set. Adults we meet in the following pages are blithely shredding those scripts to confetti, giggling as the pieces float to the ground.

The Tricky Business of Rejuvenile Classification

I should specify right at the start precisely what I mean by this new word: rejuvenile describes people who cultivate tastes and mind-sets traditionally associated with those younger than themselves. It can be used as an adjective (Those sneakers are so rejuvenile), a noun (Pee Wee Hermans brand of rejuvenalia is more subversive than Raffis), or, infrequently, a verb (Most adults are busy rejuveniling, filmmaker Randy Barbato remarked on National Public Radio shortly after I coined the word in an article in the New York Times). Existing phrases that describe aspects of the phenomenon include Peter-pandemonium, which describes the resurgent popularity of retro brands among the coveted 18-34 demographic, kidult, defined by an Italian toy company as adults who take care of their kid inside, and Twixter, a buzzword coined by Time magazine to describe unsettled adults who hop from job to job and date to date, having fun but seemingly going nowhere. Even the Concise Oxford Dictionary has weighed in, defining adultescent as a middle-aged person whose clothes, interests, and activities are typically associated with youth culture.

It should be clear that this is not simply a Gen X phenomenon. While the ranks of the rejuvenile are heavy with adults hanging on to juvenile pursuits into their thirties and forties, evidence of what British sociologist Frank Furedi calls a self-conscious regression is plentiful among adults in midlife and beyond and even among teenagers. Rejuveniles are young and old, male and female, American, European, and Japanese. That said, in talking to the toy collectors, candy connoisseurs, and other playful characters who match the rejuvenile profile, I couldnt help noticing certain demographic similarities. Most are from the urban upper classesfree time and disposable income being important components in the rejuvenile lifestyle. Those in creative fields and high technology are more likely to display rejuvenile tendencies. There appear to be more male than female rejuveniles. And while its tempting to dismiss the rejuvenile phenomenon as yet another indulgence of well-off white folks, there are plenty of counterexampleswitness the curious enthusiasm for Tweety Bird among Latino immigrants, or the mind-boggling rejuvenalia on display in Japan.