Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

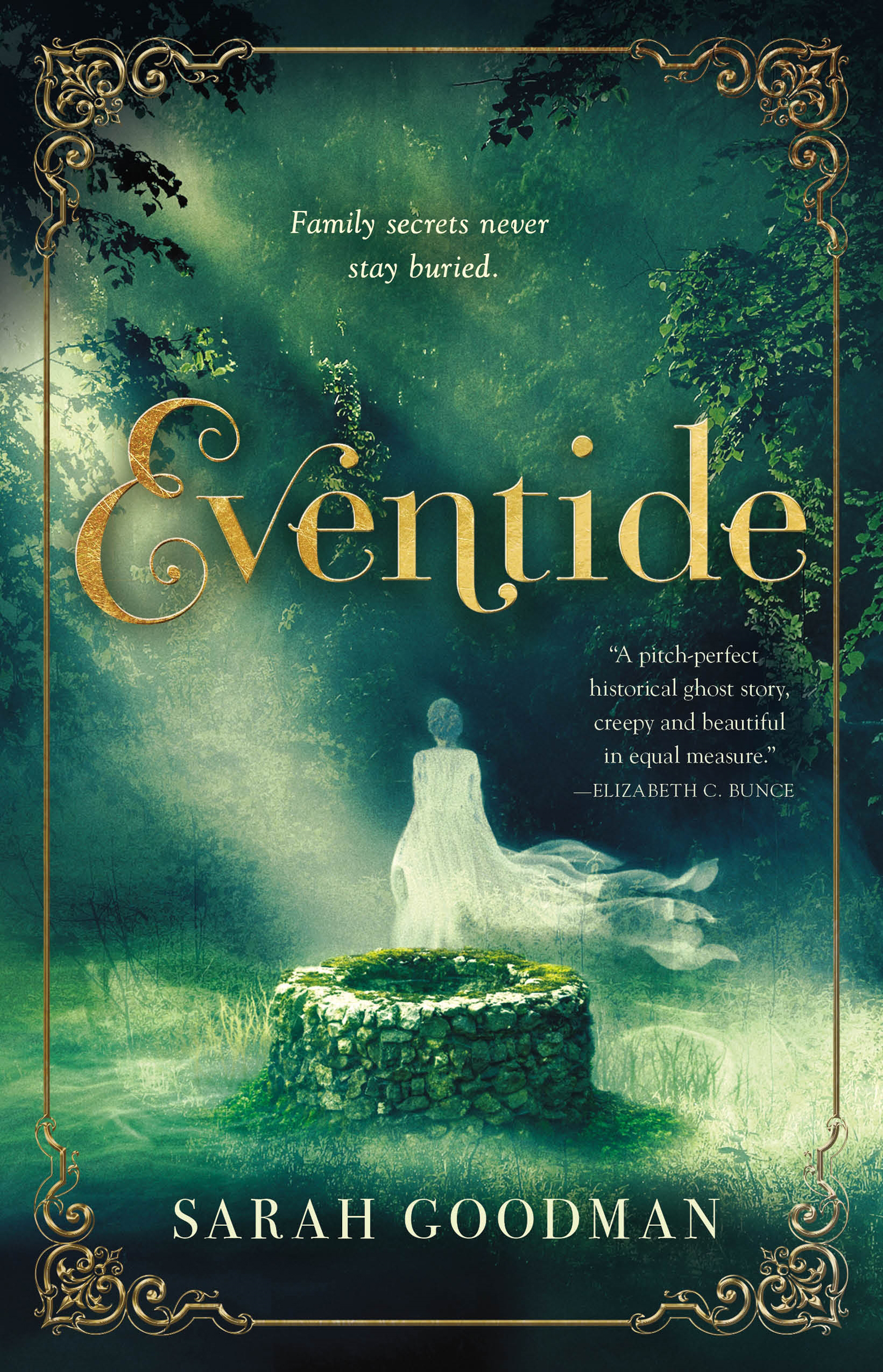

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Hannah West,

brilliant critique partner and abiding friend

Frigid wind howled across the empty fields, driving snow before it like frightened prey, rushing over sprawling farms and huddled little towns. The storm swept past a quaint parsonage nestled beside a country church. It had no concern for the girl kneeling by the winter-seared rosebushes.

Likewise, the girl paid no heed to the storm. She carried on digging at the frozen ground until a shallow hole lay before her. Carefully, she placed a hatbox in the cold earth and stared at it as the snow frosted her lashes.

She pulled a thin necklace from under her nightgown. With shaking fingers, she undid the clasp, sliding a gold ring off the chain and into her grimy palm.

Shed kept it concealed for months. Now it would be hidden forever.

The girl lifted the lid from the box. A scrap of fabric torn from an old quilt covered what lay inside. She didnt attempt to peek under its carefully tucked-in edges. Shed already kissed the perfect, tiny lips, memorized the shape of the closed eyes and the rose-gold of the babys downy hair. The ring tumbled from her hand, comingto rest on the quilt. She replaced the lid, watching the snow begin to cover the small grave.

She stood on deadened feet. Then, without a backward glance, she walked away into the storm.

June 1907

Our passenger car felt cramped as a brand-new boot and roughly the temperature of Hells sixth circle.

The orphanage had given us each a set of clothes as a parting gift, and because I was the eldest by several years, mine included an extra item: a fine hat in the latest wide-brimmed, beflowered style. I pulled it off, using it to fan my sweaty face. I doubted Id need to look fashionable where we were headed.

Humid wind rushed through the trains open windows. I hadnt realized I was listening with half an ear to the scritch-scratch of a fountain pen on paper until the sound cut off and Lilah looked up from her work, a daub of ink on the end of her upturned nose. Ive just had the most wonderful idea for a story. Im going to need more paper. She gestured with her pen to the small trunk at my feet.

Again? With a sigh, I shifted my boots so she could fling open the lid for the dozenth time. Papers shifted and slid off her lap as she scrounged for blank pages.

I have to write it down this instant, before I forget, my little sister explained with an intensity only a girl of eleven could muster.

Be careful. I dont want Papas books all bent up. And get that ink off your nose.

Scrubbing at her face with her sleeve, Lilah shoved aside the battered copies of Beckmans Treatment in General Practice and On the Prevention of Tuberculosis before coming up with a folded ivory paper. Can I use this?

My acceptance letter to St. Lawrence University poked out from between her fingers. I swallowed hard, taking it from her. Why dont you see if theres anything else to write on?

While she rummaged, I looked at the stately letterhead, remembering the triumph Id felt when I first read it. I was sure angelic choruses sang the opening line: We are pleased to accept your application for admittance followed by details of the stipend Id receive for academic merit.

All the late nights studying until my eyes burned and the candle guttered out, all the dreams of regaining our place in societyall for nothing.

Smoothing the pages, I carefully tucked the letter inside a faded book of fairy tales Mama and Papa used to read to me each evening. Nestled in bed between them, I would trace the words as they read, pretending my small fingers called the clever maidens and daring princes into being. Those days felt as distant and unreal as the magical tales that filled them.

I turned back to Lilah, who was scribbling away once again. Whats your new story about?

Lilah tapped her pen against the fresh paper resting on her knees. A girl who goes on a voyage across an unknown sea. She ends up in a land where everything is enchanted even the sky. And the clouds are made of cotton candy.

I glanced around the crowded, dingy train car as we jarred along the tracks. Why dont you ever write about things that could actually happen in real life?

Lilah regarded me with lively hazel eyes. It must be awfully dull inside your head, Verity. Youve got no imagination to speak of.

A vivid imagination can cause a world of trouble, I shot back.

I couldnt help thinking of our papa, as he used to be. Before the line between the real and the imaginary blurred in his mind, and horrors only he could see crawled out of every nook and cranny.

I retied the ribbon at the end of Lilahs strawberry-blond braid. Keeping us fed and clothed while dealing with Papas deepening madness had left me no time for whimsy. Dont bite your nails. Goodness only knows how many germs are on this train. Its a rolling petri dish.

Lilah sighed. Youre the bossiest sister in the world.

Probably, I admitted, resting my head against the window. But someone has to make sure we keep body and soul together.

Through the smudged glass, fields of sun-brittled grass spread as far as I could see. Without the towering buildings of home, the sky felt too near, like a giant lid trapping the heat of the day and us with it. Sweat slipped down my temple, stinging at the corner of my eye. The racket of the other children and the insistent click-clack-thrum of the trains wheels conspired to fray my nerves.

Wiping a damp strand of hair from my cheek, I scanned the train for Miss Pimsler. The agent from the Childrens Benevolence Society sat near the front of the car, knitting a woolen scarf, of all things.

I stood, edging up the aisle toward her, skirts swaying against my calves. The train lurched around a bend and I banged my hip against a seat. A grunt escaped before I could capture it.

Miss Pimsler looked up, her round face shining with either earnest goodwill or perspiration. She wore the self-satisfied little smile of a person who is doing good and wouldnt mind if you noticed. Do you need something, Verity?

I did, in fact. But two tickets back to New York werent an option. Could you tell me how long until we arrive?

Miss Pimsler fished an enamel pendant watch from her shirtwaist. Well be in Wheeler in just a few minutes. She closed the watch with a snick. Did you know your parents spent some time in this part of Arkansas many years ago? Thats why I decided to put you and Lilah on this train instead of one going elsewhere.

I tilted my head in surprise. They did?

Miss Pimsler nodded. I believe your mother lived here as a girl, at least for part of her childhood. Your father visited briefly, too.

Curiosity fluttered through me, followed by an old familiar heartache. Our mother died nine years ago, and Papa I trailed off. It went without saying hed been in no condition to pass down family history, even before his recent commitment to the asylum.