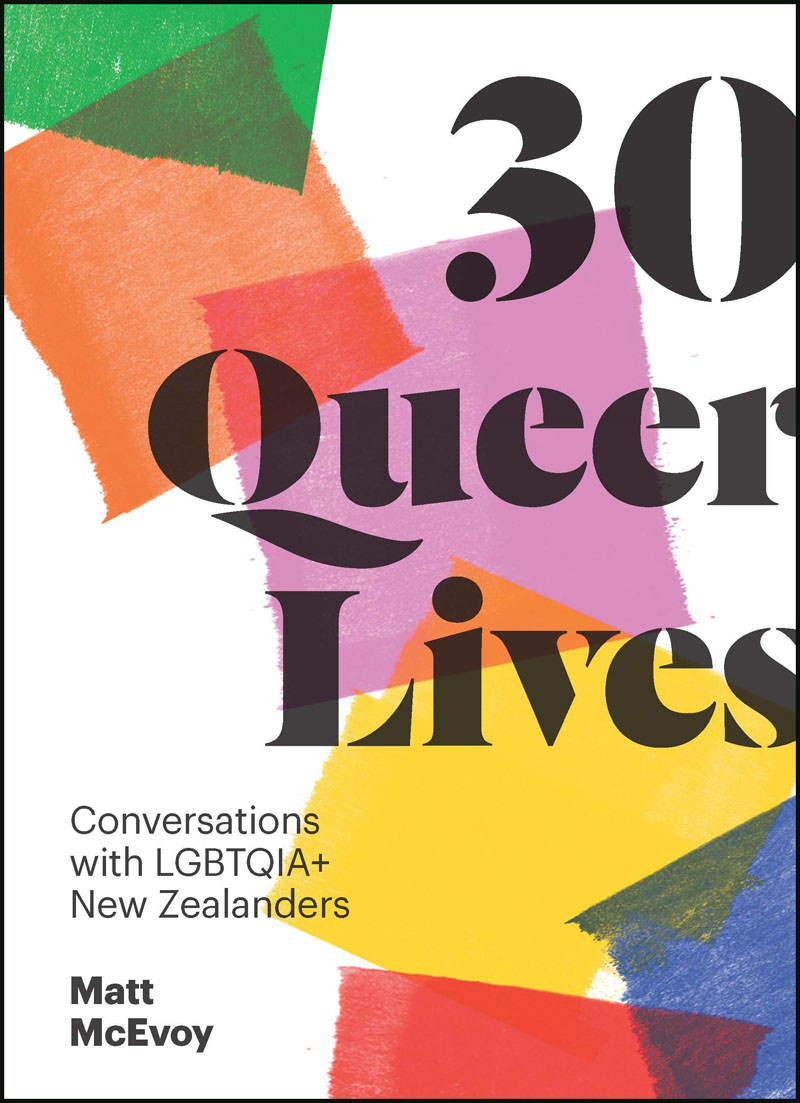

To my father for becoming a compassionate queer ally in his later years, and to my mother for her inspiring passion for life. To Yi Zhang for his unfaltering optimism, love and power to lift my spirits, and to Bain Duigan, instrumental in the conception of this book but no longer with us. And in memory of my dear friend, Sam Dunningham.

Contents

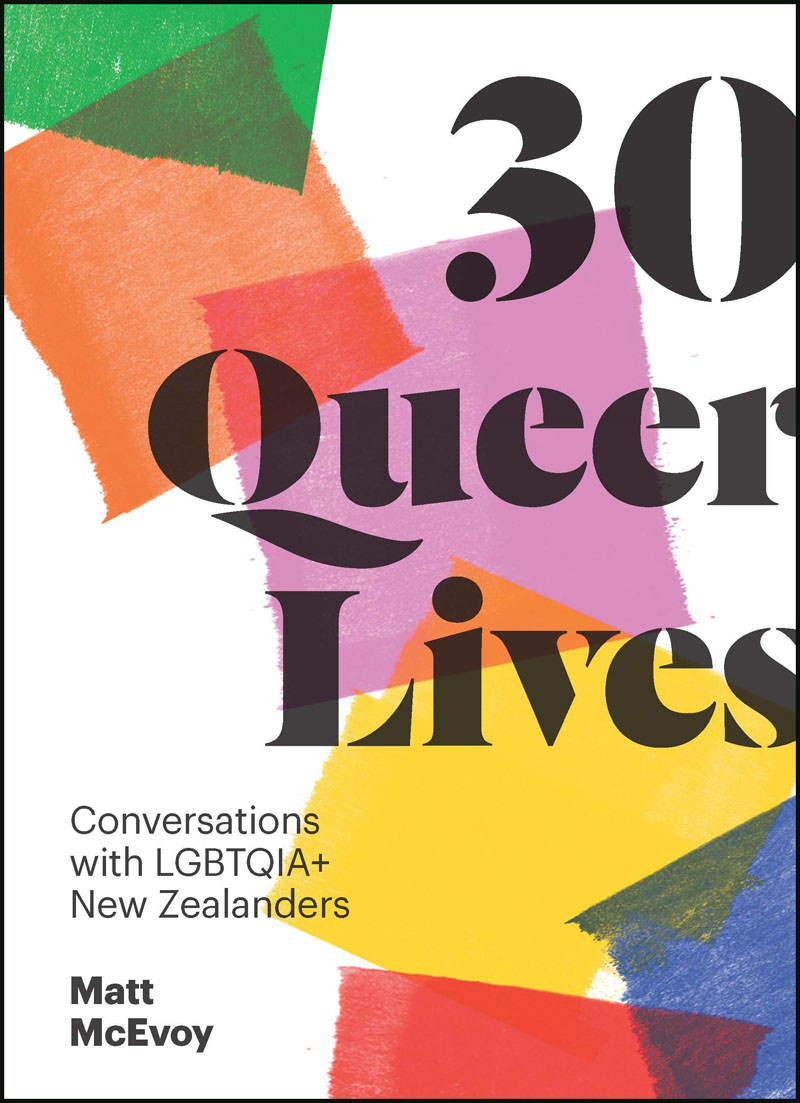

Introduction

B efore I began writing this book, I thought I had some understanding of the queer people of Aotearoa, having counted myself among them for decades.

As a gay Kiwi kid growing up through Auckland Catholic schools, books about All Blacks, Sir Edmund Hillary or wealthy businessmen were ubiquitous in the school library or bookshops, while stories about other New Zealanders were rarely, if ever, seen. My motley crew of friends and I wanted to read about New Zealanders we could relate to, but the singular elevation of the sports hero genre led to a sense of isolation, making us feel that perhaps we werent real New Zealanders.

The people youll meet inside this book hail from a wide range of backgrounds of sexuality, gender, ethnicity and privilege, and they stretch the length of the country, from Panguru to Invercargill. Travelling across Aotearoa to bring their 30 stories together, meeting them and listening carefully to their life stories cut through landscapes of hardship and tragedy, love and triumph. As they opened a window to their interior worlds, each person I met expanded my own horizons and my understanding of the diversity of human experience.

Most of these people dont see themselves as role models, but to me they certainly are. The stories of what drives them to forge ahead in the face of numerous obstacles are told with honesty and generosity. They show us how to live with integrity, optimism, hope, determination and compassion. They refuse to fade into the background, or to maintain a self-defeating faade. Instead, they channel their energies into creating lives of meaning, creativity and authenticity.

The conversations that form the base of the stories in this book took place between 2018 and 2021. The pandemic meant that the intimacy of face-to-face was sometimes replaced by technology, but even then I found that the willingness of people to share their lives far outweighed an occasional lagging internet connection.

I wanted to provide a platform for people to tell their stories without interpretation or commentary. The first-person conversational style was the most intimate and direct way to achieve this, so that readers could feel as though they were sitting in the room with us, witnessing the conversation unfold. Before we began, I took care to make it clear to each person that it was fine to discuss only the parts of their lives that they felt comfortable talking about, and I also invited them to ask me anything at any time. If my interviewees were prepared to be open about personal, emotional aspects of their lives, then it was only fair that I should offer the same candour.

Our conversations were rich with insight and hard-won wisdom. Often there was laughter and sometimes tears, and always it was an immense privilege. I hope Ive done justice to the trust theyve placed in me.

S ome of the older people interviewed for this book told me that theyve been astonished to see the progress thats been achieved over their lifetimes. As the saying goes, we see further when we stand on the shoulders of giants. In Aotearoa we remember people of mana such as Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, who created one of our first gay liberation groups in the 1970s, when her travel visa was suspended on grounds of sexual deviance; Carmen Rupe and Georgina Beyer, the groundbreaking transgender icons and activists; and Fran Wilde for her promotion of the Homosexual Law Reform Bill in 1986, which precipitated a more confident LGBTQIA+ community, one in which Rainbow Youth could be founded in 1989 and the hugely popular Hero parades, often attended by prime ministers of the day, could run throughout the 1990s. Louisa Walls Civil Union Bill in 2004 led to the celebration of full marriage equality in 2013. As I write, New Zealand has the queerest parliament in the world, and the gay conversion therapy ban has passed its first reading.

But for all there is to celebrate, there remains much to fight for. Queer people are more likely to suffer from isolation, we are over-represented in mental health and suicide numbers, and some of us are still pushed away from our families as we simply attempt to live authentic lives.

We do not exist in separate silos, and our identities are not limited to one facet or aspect. Our experience of the world is shaped by myriad intersections of race, gender, sexuality, disability, culture, age and economic status. In this book Takunda Muzondiwa talks about her Zimbabwean Christian family, Grant Robertson tells of life as a queer man and rugby fan at the highest levels of public service and scrutiny, Nathan Joe discusses being Asian and gay in Christchurch, Henrietta Bollinger recounts life at the intersection of disability and queerness, Leilani Tominiko relates being a transgender Samoan Kiwi in the world of wresting, and Ariki Brightwell considers the impacts of colonisation on Mori attitudes to queerness.

The book has revealed acceptance in unexpected places. Rural Southland and the New Zealand military upend their image as conservative bastions while the Royal New Zealand Ballet, despite being welcoming of queer dancers and choreographers, still finds the telling of queer stories a challenge.

I hope this book encourages empathy and understanding, challenges stereotypes of what a queer life can be, and offers courage and hope to people struggling in their own lives. Although this book is now complete, Ive come to see that learning from each other is a lifelong project. Everyone has a story, everyones life has something to teach us, if only we have the sensitivity to ask the right questions and take the time to listen.

Most of all, writing this book has taught me that despite all our uniqueness, what we have in common is much stronger than our differences. I hope the stories in this book help you find the courage and inspiration to show your own true colors.

Matt McEvoy

Auckland

October 2021

Grant Robertson

Grant Robertson is New Zealands Deputy Prime Minister, the MP for Wellington Central, the Minister of Finance, and Minister for Infrastructure, Racing, and Sport and Recreation. He was first elected to Parliament in 2008.

D ad decided in his mid-thirties that he wanted to get out of banking and become a minister a Presbyterian minister not a government minister so we moved to Dunedin from Palmerston North for his religious training. I was about six years old. Our social life consisted of church families and kids at the youth group. Dad was also a rugby referee and, for me, going to Carisbrook, the stadium not far from where we lived, was the non-church part of my weekend. Im the youngest of three boys, so Id tag along with my brothers to sit and watch games all day. I was obsessed with it and could name all the players. Rugby was a big thing; my eldest brother never played but my middle brother and I did. The blokey stereotypes of New Zealand men were all around me in the seventies and eighties, and I certainly sensed this, although I never felt that I couldnt be myself; I wasnt put in a box by my parents, never told what I had to be, and I still love rugby.