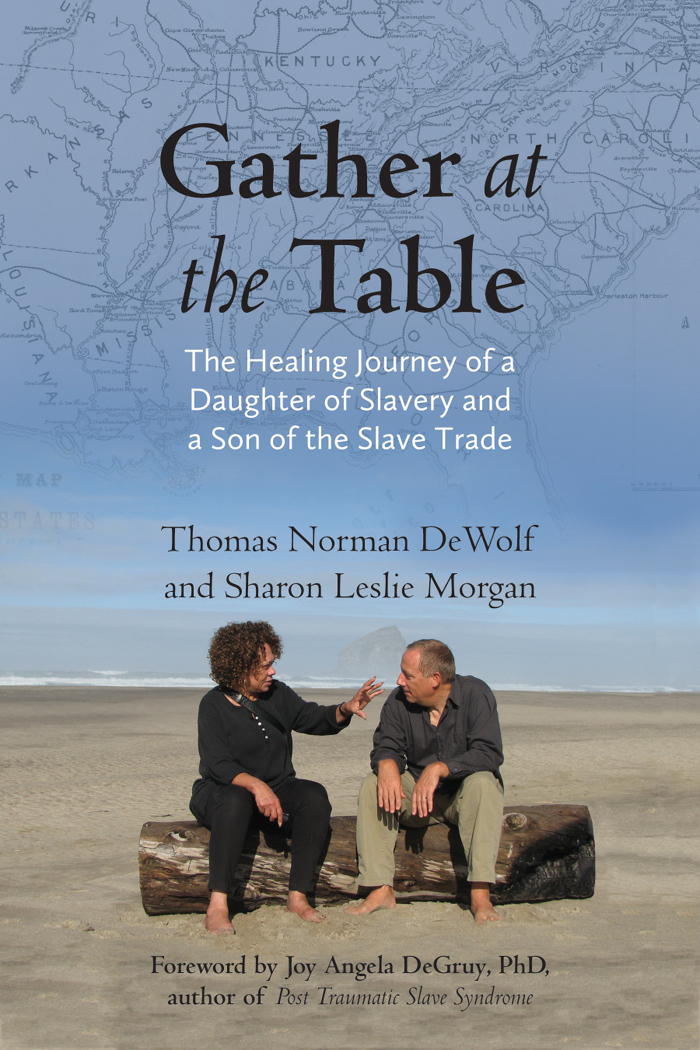

GATHER AT

THE TABLE

The Healing Journey of a

Daughter of Slavery and

a Son of the Slave Trade

Thomas Norman DeWolf

and Sharon Leslie Morgan

Foreword by Joy Angela DeGruy, PhD,

author of Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome

BEACON PRESS

BOSTON

For our ancestors who guide us

For our children who inspire us

For our grandchildren

who keep our hopes alive

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

The Recalcitrant Bat

CHAPTER TWO

Castaways from Security Island

CHAPTER THREE

Friends on Purpose

CHAPTER FOUR

Lizard Brain

CHAPTER FIVE

Many Rivers to Cross

CHAPTER SIX

The Past Is Present

CHAPTER SEVEN

Colored Water

CHAPTER EIGHT

Cycles of Violence

CHAPTER NINE

Grave Matters

CHAPTER TEN

The Crossroads of Liberty and Commerce

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Truth Be Told

CHAPTER TWELVE

The Devils Half Acre

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Ripples on a Pond

FOREWORD

The Akan people of Ghana, in West Africa, have long used Adinkra symbols to communicate important philosophical ideas and beliefs. The Sankofa icon is a mythical bird flying forward but looking backward. In its mouth is an egg. The image embodies a dual meaning. The egg represents knowledge of the past, on which wisdom is based, and signifies as well the benefit of that wisdom to future generations. The Sankofa urges us to go back and get it.

This is precisely what Thomas Norman DeWolf (a white man who is the descendant of traders and owners of enslaved Africans) and Sharon Leslie Morgan (a black woman who is the descendant of enslaved Africans) committed themselves to doing. Over the course of an epic journey, they physically traveled thousands of miles. Emotionally, they traversed oceans and centuries.

Gather at the Table is the experience of two unique and courageous individuals, seen through their particular lenses and shared from their distinct vantage points. Using genealogical records, historical references, and gut instincts, they ventured to places, thoughts, and emotions few of us would be willing to explore or experience. Inspired by a healing model, they sought to understand their history and to try and make sense of it. Their end goal was to make the connections necessary to healing themselves and, they ultimately hoped, others from the intractable wounds caused by slavery, racism, and the traumas of oppression.

In writing about their journey, they neatly weave their individual perspectives of events and experiences; these are sometimes in such sharp contrast that it is difficult to believe they were in the same place at the same time. But this is the stuff of real life; the nitty-gritty that both diametrically separates us and brings us together as human beings. Neither Tom nor Sharon shies away from the tough moments when emotions run high and opinions clash. They both recognize that the terrain is rough and not suited for the faint of heart. This is no fairytale. There are no magical remedies or mythical characters that rush forth to save the day. Like any good story, there is adventure and excitement, juxtaposed against amazing moments of personal realization and clarity.

For Sharon, race is a real place where she has lived her whole life. At times, she is overcome with grief and anger: Stolen land! Stolen people! Murder! If there is a God and he condones retribution, the white race owes a sh*tload! Yet it was a white manLawson Mabry, with whom Sharon had only corresponded about her genealogy workwho, in her words, offered emotional solace to an angry black woman who needed answers.

For Tom, race is a place he has only recently chosen to visit. Still, he was undaunted by the unknown and sometimes frightening and racially charged alleyways he would venture down. He experiences strong emotions that are equally intense: What has come as a surprise is that I feel more pessimistic than when we began. I recognize more than ever just how deeply embedded systems of oppression remain. Unwilling to give in to futility, Tom shares, What gives me hope are individual relationships. I dont care so much about laws changing if peoples hearts arent going to change.

Together, Tom and Sharon allow us to be spectators of their storywitnesses to their discomfort, humiliation, and fearin order to educate us and thus contribute to healing a nation in the throes of racial upheaval.

Theirs was an endeavor I found myself envying. I imagined walking in the footsteps of my own ancestors, learning about their lives, seeing the environments in which they lived, toiled, laughed, and cried. What would it have been like to travel with Tom and Sharon, I wondered, to be on a plantation and sleep in the Big House; to hear the stories, true and untrue, about the lives of the enslaved and enslavers; and to compare these stories with what they knew and had studied?

This is a true story about two people who defied the odds and shattered the myth that unity between black and white is not possible. Tom and Sharon offer a gift to posterity with this rich recounting of their personal histories, as well as an important piece of Americas history told through the eyes of two of slaverys children. They offer hope and encouragement to all of us who aspire to engage in a process of changeto right the wrongs of the past and forge a more just and peaceful future.

Although their journey was fraught with hardship and complexity, Tom and Sharon conclude that, in the end, it was all worth it: We began as two disconnected people. We learned. We argued. We struggled. We grew. We laughed. We cried. We changed. Along the way, we became friends.

JOY ANGELA DEGRUY, PHD

author of Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Sharons Story

F**k that dumbass Obama!

I live in a small town in a rural community in the Northeast; a working-class town of 1,230 people, predominately white. My arrival in 2010 increased the black population to twenty-four.

There are many differences between where I live now and Chicago, where I grew up, not least of which is my status here as a member of an extreme minority. There are fundamental aspects to country life that I never considered when I lived in an urban setting. I buy food at the single small grocery store near the highway. The electric power grid crashes when it storms. Four-wheel drive is required to get from my house to the road when it snowsand it snows a lot. Im wary of the bear that regularly rifles through my garbage can. And I must go to the post office in person to collect my mail, which is where I had an experience that is indelibly etched in my mind.

I usually go to the post office once a week, on Friday. On this particular day, I collected my mail as usual, returned without incident to my car, and prepared to head home. As I paused to wait for traffic before exiting the parking lot, a man pulled up beside me in a silver SUV. After some moments, I realized he was staring at me.

My white people alert system revved up. I jumped to the conclusion that this man was looking at me because Im black. I hadnt been here long enough for it to be anything else. Although Im fair-skinned, there is no way most people would mistake me for anything other than black.

Not wishing to give in to my paranoia, I smiled, as any neighbor would do. To my shock, he yelled the Obama invective at me and sped off, tires spitting gravel.

I was speechless. Why did this man target me? Was it the Obama sticker on my bumper? Was it my Illinois license plate (Obamas home state)? Does he think black people were solely responsible for electing Barack Obama to be the first African American president of the United States? Do I represent all black people in his mind? Would he have said the same thing to a white person?