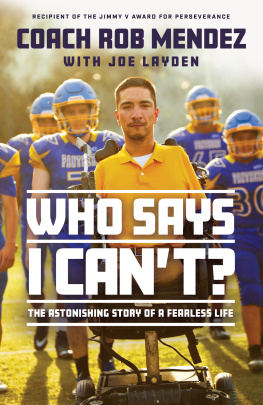

Who Says I Cant?

Copyright 2021 by Robert Nieblas

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by Harper Horizon, an imprint of HarperCollins Focus LLC.

Any internet addresses, phone numbers, or company or product information printed in this book are offered as a resource and are not intended in any way to be or to imply an endorsement by Harper Horizon, nor does Harper Horizon vouch for the existence, content, or services of these sites, phone numbers, companies, or products beyond the life of this book.

ISBN 978-0-7852-3941-3 (eBook)

ISBN 978-0-7852-3940-6 (HC)

Epub Edition July 2021 9780785239413

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021930682

Printed in the United States of America

21 22 23 24 25 LSC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my dad, Robert Sr.; mother, Josie; sisters, Jackie and Maddy; both tias, Tota and Cindy; and of course, my Grandpa Danny and Grandma Mona. I dedicate this book to my parents and the rest of my family for their belief in me, their support, and ultimately for bringing love and strength into my heart. My father was my biggest advocate for me growing up, not allowing for anyone else to see me any different and always reminding me to focus on what I am able to do, rather than what Im not able to do. And my mother showed me that love is everything. She has a big heart and is my biggest supporter. I love you all very much, and I consider myself one of the luckiest individuals to grow up in the family I did.

CONTENTS

Guide

AUGUST 26, 2018

I ts funny the way a good day can turn bad without any warning. That is a fact of life for anyone, of course, but its particularly true in my case.

Today is a beautiful summer Sunday in the Bay Area of Northern California, specifically in the town of Morgan Hill, where my parents live. Im staying for the weekend, while my caretaker is out of town. Im hanging out in the garage, just shooting the breeze with my dad as he does some work, the way we did while I was growing up. The sun is fading in the evening sky, and music is playing in the background. Its comfortable, familiar, peaceful.

Reflexively, I decide to check my phone. It sits in a cradle just below eye level on my elevated, motorized wheelchair. I lean forward to grab the stylus with my teeth. Its a simple maneuver, one Ive executed thousands of times before, and I do it without a thought, like anyone else who compulsively plays with their smartphone. Just a couple of quick pecks, and Im in sync with the digital world: answering texts and emails, checking Instagram and Twitter feeds, getting ready for my fantasy football draft.

You know, the usual stuff.

But something happens as I reach for the stylus. It registers first as a wave of disorientation. Im used to feeling the firm snap of a safety belt holding me in place when I move too quickly or too far. And believe me, I do that a lot. I often thrash about in my chair, gesticulating with my head and shoulders, expressing emotion with what I have, rather than worrying about what I dont have. I lean and twist and turn, sometimes as a means of expression and sometimes in an attempt to alleviate the enormous strain that my spine bears all day, every day. For a guy stuck in a wheelchair, or maybe because I am stuck in a wheelchair, I have an abundance of energy. To minimize the chance of injury, my chair is equipped with two straps: one for the chest, and one for the waist. Much to the dismay of my friends and family, I rarely use the chest strap. Too confining. I figure the waist belt is sufficient. Usually it is.

Unless you forget to use it.

You know how they say everything slows down when youre in an accident? Well, its true. I can feel myself leaning forward, and at some point, I realize there is nothing to stop the progression. My head goes right past the stylus and the phone, and my torso dutifully follows. I am out of the chair now, hurtlingcan that possibly be the right word when falling from a height of only four feet? Yes, it seems exactly righttoward the garage floor. I can see the concrete rising to greet me. The feeling of helplessness is impressive, if not overwhelming. I can do nothing to stop the impending catastrophe. I have no arms to break the fall, no legs to absorb some of the impact. I turn my head to the side.

And close my eyes.

I wake in the passenger seat of my fathers Chevy Suburban. His hands are locked on the steering wheel, his eyes red and wet. We are racing down the interstate, toward Saint Louise Regional Hospital.

Dad, its okay. Im all right.

This is not true. My head throbs. My face is on fire. Liquid drips into my left eye, sticky and stinging.

Please, Robert, he says. Be still.

I look down. Blood is everywhere: on the seat, on my clothes. I blink hard, trying to clear my vision. I know Im hurt, and though I dont know exactly how bad, Im worried not only about my health but what my injuries might mean for the new direction my life has taken.

Right now, though, I mainly feel bad for my father, who has been through so much with meand who taught me never to focus on what I couldnt do but rather on what I couldand how he will process all of this. Bad enough to see your only sons head smack against a concrete floor with the sickening sound of a pancake being slapped against a griddle (thats exactly the way my father would later describe it). But to wonder whether youd buckled his seat belt, or buckled it effectively, was even worse.

It could have happened to anyone. Anytime. And, ultimately, its my responsibility. I am not a child. I am a grown man, thirty years old. But in that moment, there is no consoling my father.

Dont worry, Dad.

He doesnt respond. He simply cries.

At the hospital he whisks me into the emergency room, carrying me like a toddler against his chest and shoulder. Its a head injurythe kind that gets you pushed right to the front of the line at the ER. Within minutes, Im surrounded by doctors and nurses cleaning my wounds and assessing the damage, conversing calmly but forcefully in the staccato rhythm of trauma care. The pain ebbs and flows as they wheel me through the hospital for X-rays and a CAT scan. Six stiches are required to close the gash above my left eye, but of greater concern are the fractures to my orbital bone and cheekbone. The doctors say Im lucky. It could have been worse. A face-first plant would have shattered my nose. Had I turned too far to the sidea natural and perfectly reasonable response of self-preservationI could have struck my temple. If that had happened, I might not have even made it to the hospital.

So, yeah, I got off easy.

When can I go home? Before anyone can answer, waves of nausea rock me. I start vomiting. And I dont stop until the meds kick in a few hours later.

Im discharged at seven oclock the next morning. My head is still throbbing, my neck aches so badly I can barely move, and my face feels as though its been rubbed raw with sandpaper. They tell me the obvious: Ive suffered considerable damage, including a concussion, and that while the outcome could have been worse, Im going to feel lousy for a while.

Take it easy, one of the docs suggests. No work.