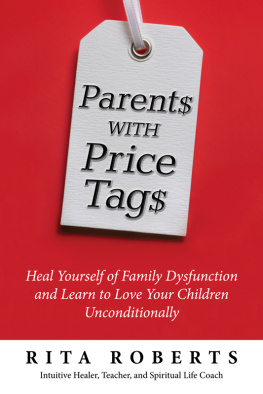

A SK THE S TARS

Anthony Mugo

Published by

Longhorn Publishers (K) Ltd.,

Funzi Road, Industrial Area,

P.O. Box 18033 00500,

Nairobi, Kenya.

Longhorn Publishers (U) Ltd.,

Kanjokya Street, Plot 74,

Kamwokya,

P.O. Box 24745,

Kampala, Uganda.

Longhorn Tanzania Ltd.,

New Bagamoyo/Garden Road,

Mikocheni B, Plot No. MKC/MCB/81,

P. O. Box 1237,

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Anthony Mugo 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior

written permission of the Copyright owner.

First published 2014

ISBN 978 9966 31 062 0

Printed by English Press Ltd., Enterprise Road, Industrial Area, P.O. Box 3012700100, Nairobi, Kenya.

FOREWORD

The National Book Development Council of Kenya (NBDCK) is a Kenyan nongovernment organization made up of stakeholders from the book and education sectors. It promotes the love of reading, the importance of books and the importance of quality education.

The Burt Award for African Literature project involves identification, development and distribution of quality story books targeting the youth, and awarding the authors. It is funded by Bill Burt, a Canadian philanthropist, and implemented by the NBDCK in partnership with the Canadian Organization for Development through Education (CODE).

The purpose of the Burt Award books such as Ask the Stars is to give the reader high quality, engaging and enjoyable books whose content and setting are portrayed in an environment readers can easily identify with. This sharpens their English language and comprehension skills leading to a better understanding of the other subjects.

My profound gratitude goes to Bill Burt for sponsoring the Burt Award for African Literature in Kenya. Special thanks also go to the panel of judges for their dedicated professional input into this project. Finally, this foreword would be incomplete without recognizing the important role played by all NBDCK stakeholders whose continued support and involvement in the running of the organization has ensured the success of this project.

Ruth K. Odondi

Chief Executive Officer

National Book Development Council of Kenya

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The Burt Award for African Literature recognizes excellence in young adult fiction from African countries. It supports the writing and publication of high quality, culturally relevant books and ensures their distribution to schools and libraries to help develop young peoples literacy skills and foster their love for reading. The Burt Award is generously sponsored by a Canadian philanthropist, Bill Burt, and is part of the ongoing literacy programs of the National Book Development Council of Kenya, and CODE, a Canadian NGO supporting development through education for over 50 years.

Chapter ONE

S ince you love fighting so much, I will give you a chance to do so. Bring a stick each.

I looked at my father in disbelief. He never minced his words and I feared his judgment. Without doubt we were in for a thorough beating. Within ten minutes, we were back with the sticks.

This tells how much you hate one another, he said, testing the sticks. You will fight following my rules.

The rules were simple. We would cane each other in turns until the two sticks get broken into pieces. I was the first one to work on Njorua, my elder stepbrother. Quick analysis told me that I was the underdog since Njorua was more energetic and his stick was thicker, which by Fathers inference, meant that he hated me more than I hated him. I decided to employ every ounce of strength in me to mete out maximum pain, if not equal. I raised my stick and caned Njorua with force and his hands ran to his buttocks. I hated Fathers rules because it meant that I would receive as much punishment as I administered. Fighting, as postulated by David against Goliath, is about tactics. However, instead of punishing us in person, Father was using us to punish ourselves in pretext of fighting. By the third round, I was ready to surrender.

I dont want to fight, I said.

Then take his position! Father hissed. Fighting is about inflicting pain, fighting is about maiming, even killing; fighting is no fun!

I dont want to fight! I wailed.

We dont want to fight, Njorua said amid sobs.

Are you cowards now? Are you so jerry? Fight! I raised the cane with my two hands and brought it down with force. Njorua was all too eager to avenge himself. He caned me so hard that I thought my shorts had got torn.

Please forgive us, I said crying. I shouldered the bigger burden of pleading with Father because by caning Njorua, the punishment would go on. We will never fight again. I sobbed

Now, why were you fighting?

He called me Kabira.

What did he call you?

He called me bastard first.

Father regarded us coldly for a long, disturbing moment, then ordered us to look each other in the eye.

Now that you have fought, what has changed? Possibly, you now hate one another more for inflicting so much pain on each other, but you are still brothers. Why dont you learn to live; why dont you learn to coexist? I am the law here and I say no fighting. If you must fight, join the army.

Father ordered us to deworm the calf, which entailed tying it to a post; one person wedging its mouth wide while the other poured the dewormer down its throat. We were also supposed to fetch banana stems from the garden for the cattle. The wheelbarrow had a wobbling wheel necessitating one person to pull while the other pushed it.

I was resting after executing the tasks when I realised that after ensuring we have beaten the hell out of each other, Father had cunningly ensured that we worked together. There was no way one person could deworm the cow or ferry the banana stems. It required the two of us to cooperate and physically execute the tasks.

* * *

The animosity in the family had started two years before. We had just cleared supper when our father said, I am so proud of each one of you. You make me whole. It has not been so easy. We should have had this conversation a long time ago. Maybe you have heard what I am about to say. I take the blame.

I had heard so many things I couldnt figure out what Father was about to say. I waited with bated breath.

I was married before I met your mother.

That was news to me and to my two sisters and brother, judging from their expressions. I was ten years old; Njorua, being the oldest, was twelve. Antonnina was eleven and Sarah seven. I wondered why father considered it important.

As fate would have it, my first marriage did not work out. Nevertheless, God blessed it with two wonderful children. After the collapse of my first marriage, I met your mother and we decided to live together. She vowed to treat everyone as her own child. To this day, she has kept her promise and I greatly respect and adore her. Thank you, my love. You all make me so proud I can hardly put it in words. We are family.

Father stopped as if debating with himself whether to continue or not. He had our full attention now. His discourse had taken a disturbing twist because it meant that two of us had a different biological mother from the one we knew.

Njorua, Antonnina, Father went on, I am sorry if you have heard this before. Your biological mother is Ascar Simane. But that is no cause for worry; Mutumia Mutana here is as good as your real mother. She cannot replace Simane, but she can help you grow. It is Gods noble plan that we are family.