Copyright 2013 by Master Wings Publishing LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or

reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States by Master Wings Publishing LLC,

an imprint of the Pritzker Military Library.

A limited edition of this book was originally published as Poems for Pilots (and other people).

The following photographs were provided by the persons indicated,

whose contributions are gratefully acknowledged:

jacket photograph of prison gate iStockphoto.com/peeterv

jacket (hand)Charles Rue Woods; page 10Roger Knopf; page 163

and bottom of page 165L. Matjasko; and cup and medalsJohn Borling.

ISBN: 978-0-615-65905-3

eISBN: 978-0-615-65906-0

Limited Cloth Edition ISBN: 978-0-615-71782-1

Printed in the United States of America

by R.R. Donnelley & Sons Company

Designed by Charles Rue Woods

First Edition

Distributed by Greenleaf Book Group LLC

www.tapsonthewalls.com

FIRST and ALWAYS: To my wife, Myrna

A sunset lover wedded to your dawn, I too shine and depend upon your light and love to carry on. Thanks, Honey.

Thanks also to our daughters, Lauren and Megan, who served their country in special growing-up ways and whose energy and love sustain. Dad knows.

Contents

Section I

Strapping on a Tailpipe

Section II

POW and Other Dark and Bitter Stuff

Section III

The Holidays and Hollow Days

Section IV

SEA Story (Southeast Asia Story)

Foreword

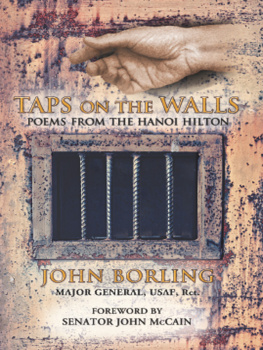

T he great honor of my life is to have served in the company of heroes. In captivity in Vietnam, we fought every day to keep our honor intact, our minds sharp, and bodies functional. John Borling, a POW for over six and a half years, won this fight for himself and contributed greatly to the morale and survival of the rest of us with his poems and incredible talent for storytelling.

Taps on the Walls: Poems from the Hanoi Hilton reveals Johns incredible creative and mental effort. Surviving alone or in semi-isolation, John first used his poetry as a weapon to stay sharp. Using the forbidden tap code, his poems were tapped through the walls from one POW to another to boost morale and, as a legacy for his wife Myrna in case he didnt make it home. He did survive and went on to become a General Officer in the Air Force.

I met John after the Son Tay raid in November 1970. While that raid failed to liberate any prisoners, it forced the consolidation of POWs into larger groups at the Hanoi Hiltona remarkable blessing. If you have never been deprived of liberty in solitude, you cannot know the ineffable joy you experience in the open company of other human beings, free to talk and joke without fear. The strength we acquired through fraternity with our fellow soldiers was immeasurable.

This environment brought forth the talents of men like John, whose prowess as a teller of tales and as a poet was already well-known. In the larger group, he would entertain us with stories from a movie or a bookmaking them live in our imaginations with all the reality of a movie screen or a printed page. His personal collection of poetry, mentally composed and memorized over the course of his imprisonment, was another valuable source of mental stimulation and discussion.

It is most fitting that on this 40th year anniversary of our release from prison in Vietnam that you can know and appreciate Johns remarkable work as we did during our darkest days in the Hanoi Hilton. Keeping a sense of humor while in prison was indispensible to our survival. Johns words express that humor and more, as there are some stories of the soul that extend far beyond prison walls. Enjoy.

Senator John McCain

POW, North Vietnam, 1967-1973

Introduction

T his is a story about the power of the unwritten word. It is a redemptive storyhow poetry helped save me during six and a half years as a POW in North Vietnamese prison camps.

Ubon Air Base, Thailand: Flying combat for six months. On 1 June 1966, my life changed forever.

My 97th fighter mission was a volunteer-only night sortie deep into the heart of heavily defended North Vietnam. Three more flights north after this one and Id be finished with my hundred-mission tour. With orders in hand to a fighter base in England, there was good duty ahead. Actually, pretty far ahead, because I had volunteered to fly another hundred missions before leaving the combat zone.

So, on that bright, moonlit June night, it was low and fast over the mountains northeast of Hanoi in an F-4 Phantom. Reaching the target area, heavy ground fire ripped into the jet. Out of control. No controls. Upside down. The jet was dead. I had to get out. Eject. Ejected and hit the ground; it was that close.

I hit on a long, steep, furrowed hill and went bouncing downhill like some kind of crazy jumping bean and ended up in a beat-up heap at the bottom. That hill probably saved my life. I was alive, but with disabling pain in my back, ribs, and ankles. There was blood everywhere. I couldnt walk. I was broken. The locals were all around me, shooting into the bushes and jungle to flush me out. I had to get away. I crawled into a log and passed out.

When I came to, they were gone. I heard truck traffic maybe fifty yards away on Highway One, which led northeast to China. There was no rescue possible. I was in too deep. I had to get out on my own. I had to break the no-contact-with-the-enemy rule. I would hijack a truck and make them drive me to the coast. Then Id commandeer a boat and head south. It seemed like a good plan at the time. It was the only plan that made sense. Surrender was not a plan.

It took a long time crawling, but finally, beggarlike, clutching my service revolver, I huddled on the side of the road. A truck came at me. I yelled and waved my gun. Nothing; it rolled on by.

Shit. I needed to be in the road. Had to make em stop or run over me. A branch became a crutch, and I struggled out to the middle of the rutted track. A couple minutes later, another truck. I waved my gun and stared down the driver. That did it. Success. I had jacked a truck.

Unfortunately, it was a truck full of North Vietnamese regular troops. Despite my shouted orders to surrender, they didnt. I ended up tied up, stripped naked, and lying in the road.

Thats how it began. Twenty-four hours later, I was dragged into the infamous Hoa Lo prison (aka the Hanoi Hilton). I would be a POW for more than six years and eight months. My wife would not know if I was alive for years. Somehow, she felt me and carried on while all others doubted. My nine-month-old daughter would grow and dream of a father walking her to school one day. I would have the same dream. She would be seven and a half before our dreams came true.

But happy endings would come hard, with hate, horror and humor, honor and shame coming first. Horses of hope (or hopelessness) galloped for years with no finish line in sight. God was very close or very distant. Freedom and flying were unreachable stars.

For many years, my fellow pilots and I were held alone or in semi-isolation. The enemy wanted us weak, despondent, and totally cut off. Our challenge was to keep the faith, carry on, and stay true to one another. For that, we had to communicate.

Next page