Copyright

NEW DAWN PRESS GROUP

Published by New Dawn Press Group

New Dawn Press, 2 Tintern Close,

Slough, Berkshire, SL1-2TB, UK

e-mail: salesuk@newdawnpress.org

New Dawn Press, Inc., 244 South Randall

Rd # 90, Elgin, IL 60123

e-mail: sales@newdawnpress.com

New Dawn Press (An Imprint of Sterling Publishers (P) Ltd.)

A-59, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-II,

New Delhi-110020

e-mail: info@sterlingpublishers.com

www.sterlingpublishers.com

www.newdawnpress.org

Better Eyesight without Glasses

Copyright 2005 by Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

ISBN 1 84557

All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or

by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without prior written permission of the publisher.

Introduction

Of all our faculties, sight has consistently been considered the most miraculous and the most beneficial. Biology shows that the eye is, quite literally, a part of the brain, the place where the brain rises to the surface. Our eyes enable us to see things. But because of their complex mechanism, they are peculiarly liable to defect, breakdown and injury. Modern civilisation also places an unprecedented strain on the optic system of the ordinary person. Television screens, artificial lighting, abundant reading materials, poor diet, tobacco, alcohol, certain drugs, can all contribute to deteriorated vision.

This book is designed to provide the lay person with a comprehensive guide to how the eyes work, how to look after them, some easy-to-follow exercises for relaxation of the eye muscles, and better eyesight without glasses.

01. The Optics Of The Eye

Sight can be the most informative of all the senses. Our eyes constantly explore the world by scanning and inspecting the details of our surroundings. They adapt quickly to suit the surroundings. They can shift focus instantly in any direction, and their movements are rapid.

They adapt to the amount of light as well, letting in only that much as is required in bright sunlight but opening up to gather as much light as possible at night and in dim light.

External muscles of the eye

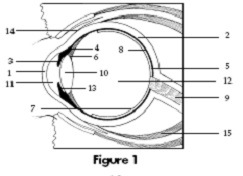

The eyeball is a slightly flattened sphere about an inch in diameter. It lies in a bony socket lined with fatty tissues, thus protecting the eye from any injury. Each eyeball is made up of three layers: the sclera, the choroid and the retina.

Sclera

This is the outer layer, consisting of a tough, protective tissue, which holds the eye in shape, and provides points of attachment for the external muscles that move it.

Behind the eyeball, the sclerotic layer is pierced by the optic nerve. The sclerotic tissue is opaque and normally white in colour. The visible part is covered with a transparent membrane called the conjunctiva which contains a network of tiny blood vessels that become enlarged if injured or inflamed, making the eyeball bloodshot.

There is a domed transparent window in front of the sclerotic layer, called the cornea, which lets light into the eye one of the few tissues in the body having no blood vessels in them. Tears, one of the natural safeguards for the cornea, come from the lachrymal gland, behind the top eyelid, and drain into the narrow tear duct at the inner corner of the eye which leads to the back of the nose.

The tears, consisting of water containing salt and a bacteria-killing substance, spread over the cornea, and wash away the dust particles.

Choroid

The middle layer of the eyeball, the choroid, is dark brown or black, and the pigment absorbs excess light, thus preventing scattering of light in the eye and blurring of vision.

Many vessels, carrying blood and other fluids to the rest of the eye, pass through the choroid. The choroid, at the front of the eye, thickens to form a ring of muscle called the ciliary body which encircles the cornea. Ligaments attached to the ring hold the crystalline eye lens in its correct position. The lens can alter shape to complete the focusing.

The eyeball is divided into two chambers by the ligaments. The larger chamber, behind the lens, is filled with a transparent jelly, called vitreous humour, while the smaller one, in front of the lens, contains a watery liquid known as aqueous humour both these fluids aid the eyeball in retaining its original shape.

The coloured part of the eye is the iris, which is also an extension of the choroid layer. It is suspended between the lens and the cornea. The circular opening at the centre of the iris is known as the pupil, which allows light into the eye. The iris automatically dilates and contracts the pupil to control the amount of light entering the eye.

Retina

The inner layer lining the back of the eyeball is called the retina.

This is a delicate, thin membrane whose surface is covered with a network of veins and arteries. Light travels through layers of nerve tissues underneath the retinal blood vessels before it reaches the lightsensitive receptors the rods and the cones. The rods are slender and flat-ended, and the cones are thick and pointed. They are connected to nerve fibres that come together to form the optic nerve.

There are no visual receptors at this point, so it is not sensitive to light. It is known as the blind spot. It has no effect on vision because, when the eye is directed at something, its image falls on the central part of the retina, called the fovea.

The blind spot is in the field of the peripheral vision the part seen out of the corner of the eye. The cones contain a violet pigment, and the rods a purple pigment, known as rhodopsin. When light strikes the rods and cones in the retina, chemical changes take place, resulting in bleaching of the pigments. Bleaching stimulates nerve signals that travel to the brain, where they are interpreted as a series of images. Bleaching occurs so quickly in the rods that they cannot operate in bright light they are at their best in dim light, registering shades of grey, or at night when they can detect faint light sources.

The cones increase in concentration towards the back of the retina. In the centre of this area lies the fovea, a depression in which there are no rods, only cones. This is the area of sharpest vision, the point upon which light rays are focused when the eye is directed towards a particular point on an object.

It is sensitive to fine details because each of the cones is connected to a single nerve fibre conveying an impulse to the brain.

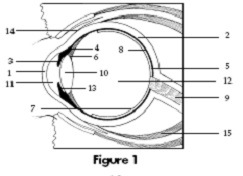

| 1. Cornea | 9. Optic nerve |

| 2. Sclera | 10. Lens |

| 3. Iris | 11. Aqueous (anterior chamber) |

| 4. Ciliary muscle | 12. Vitreous (posterior segment) |

| 5. Choroid | 13. Aqueous (posterior chamber) |

| 6. Suspensory ligaments | 14. Conjunctiva |

| 7. Retina | 15. Eye muscle |

| 8. Fovea |

Refraction and focusing

When the light enters the eyeball, it is bent, or refracted. It passes through the conjunctiva, the cornea, the aqueous humour, the lens and the vitreous humour, before reaching the retina.

About 70 per cent of refraction takes place in the cornea. The lens carries out fine focusing of the light rays for long-distance vision or close vision. Light rays from a nearby object diverge as they approach the eye and, therefore, have to be squeezed together to focus them in a point exactly on the retina.

Light rays from a distant light source are almost parallel and so do not have to be refracted to the same degree.