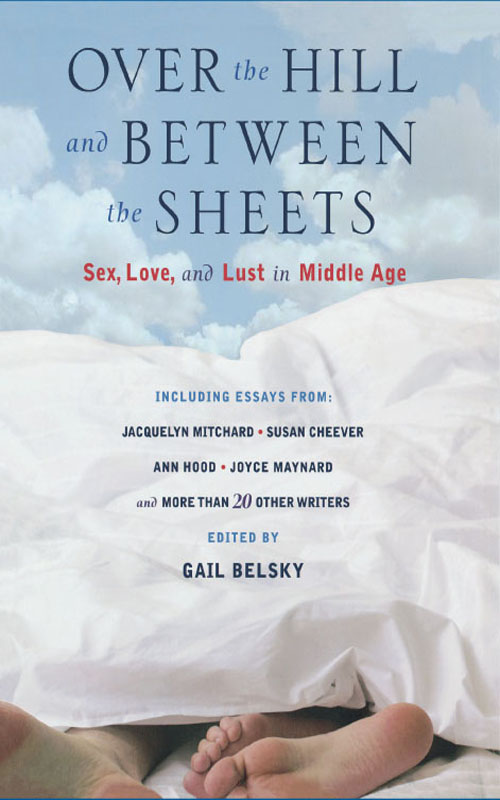

Copyright 2007 by Gail Belsky

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Springboard Press

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

www.twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First eBook Edition: September 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56521-9

Springboard Press is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing. The Springboard name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group USA.

To Julian,

my partner in change,

who gladly gave me my dream

The idea for this book came innocently enough when a friend made a confession at dinner one night. He often said things to get a rise out of my husband and me all right, just me. But as we lingered over mussels and fries, he blurted out something that took us all by surprise: Hes hot for middle-aged women. Suddenly, he finds themus?to be incredibly alluring. (I assumed this included his wife, who was sitting right next to him, but that wasnt clear.) He even slows down at the school-bus stop to check out the moms, wondering, and I quote, what their lives are like and what theyre thinking about.

The idea for this book came innocently enough when a friend made a confession at dinner one night. He often said things to get a rise out of my husband and me all right, just me. But as we lingered over mussels and fries, he blurted out something that took us all by surprise: Hes hot for middle-aged women. Suddenly, he finds themus?to be incredibly alluring. (I assumed this included his wife, who was sitting right next to him, but that wasnt clear.) He even slows down at the school-bus stop to check out the moms, wondering, and I quote, what their lives are like and what theyre thinking about.

Youve got to be kidding, I said, laughing. I poked fun at him the rest of the night but couldnt get his admitted proclivity out of my mind. The next time I was on the phone with a man other than my husband I had to ask: Do middle-aged men really feel this way?

Absolutely, said author and essay contributor Cameron Stracher. His forty-something friends often talk about middle-aged women, or Yummy Mommies, as one of them likes to say.

Where had I been?

In a cave, apparently, along with many other middle-aged women who have never once thought of cruising barbershops or bus stations for interesting-looking dads.

I am the last person Id expect to do a book on middle-aged intimacy. The public discussion of sexmine or anyone elsesmakes me squirm. (For more on this sentiment, see Satellite Sister and author Lian Dolans essay; she sums up my feelings perfectly.) But I was so intrigued by the Yummy Mommy thing that I wanted to do this book almost immediately.

I figured thered be a disconnect between how middle-aged men and women experience love and sexuality, and that a collection of essays from both would result in an amusing he said/she said dialogue. But in the process of talking to male and female writers I discovered that their stories are not disconnected at allnor are they truly about sex. In the broadest sense, they are reflections of who we are and how we cope with midlifes ups and downs.

By this age we know that change is constant, and often unpredictable. Some changes hit like bricks: illness, infidelity, pregnancy, divorce, and head-spinning love. Others are subtle and creeping, the result of living four or more decadeswe get bored, grow weary, wise up, take stock, change direction, seek answers. We wake up to find that our love lives, among other things, have mutatedfor better or for worse, but not forever. And we accept that.

Last year my annual mammogram revealed an atypical growth. By the time they took it out and biopsied it, I had spent eight weeks waiting to hear that I didnt have cancer. Eight weeks of stress and virtually no sex. Fear and worry had made me so tense that I was literally untouchable. Ironic, because there had been a period in my marriage, not so long ago, when I was equally unavailableout of anger then, not anxiety. (The details are different, but the emotions are similar to what writer Eric Bartels describes in his essay.) Then a year or so ago, and for no particular reason, the anger lifted and sex became fun and easy again.

First a subtle shift.

Then a brick.

I walked away from the surgery with a huge sense of relief (obviously) and an unwanted souvenir: a one-and-a-half-inch purple scar and puckering indent above my right nipple. It was an ugly intrusion, and if I were younger, if I didnt already have stretch marks, cellulite, wrinkles, and a scar near my collarbone from skin cancer surgery, I might have been devastated. Instead I was just depressed.

My breast, the source of so much pleasure over the years, was now nasty-looking and painful. The scar was a built-in reminder that many women my age are not as lucky as I had beenand that I might not be so lucky next time. There was nothing enjoyable about that breast now, as far as I was concerned. But my husband thought differently. He wasnt fazed by it. Wasnt repulsed or afraid to touch it. So eventually my breast became just my breast again with one big nick and dent. And I moved on.

When change hit novelist Caroline Leavitt, it nearly killed. In her early forties, after giving birth to her first child, Leavitt became deathly ill with a rare blood-clotting disorder. It was months before she could hold her baby and even longer before she could sleep with her husbandor even think about sleeping with him, since the state of arousal would stimulate blood flow and might cause her to bleed to death. She went overnight from being the sexiest pregnant woman alive to a being a bloated, battle-scarred survivor. And still, she managed to find her way back. To sex. And health. And looking toward the future, however altered it might be.

Change delivered editor and writer Michael Corcoran from a nearly sexless second half. Married young, he and his wife had three kids before they were twenty-five, effectively killing any real desire for sex. They might have gone on like that foreverhe was resigned to it, in factbut one little move shook up everything.

More or less, better or worse, empty or fullin middle age, we just deal.

The essays in this collection are as varied as the lives and experiences of the writers themselves. Sarah Mahoney discovers phone sex in wartime. Jacquelyn Mitchard finds love in a hammock with a younger man. Anne Burt loses a love child. Cameron Stracher tries to escape real life with an ill-fated weekend in Vegas. Ann Hood and her husband are torn apart by grief and held together by passion.

They all strike a chord because they all reflect a universal truth: with age comes acceptance.

Defining middle age for the purposes of this book was tricky since, really, it is a stage more than a statistic. If I had taken the mathematical approach using the latest government life-expectancy figures, the male contributors would all be thirty-seven and the females would all be forty. If, however, I had used Freedictionary.com as my guide, theyd range in age from forty-five to sixty-five. And had I consulted Answers.com, which defines middle age as the time of life between youth and old age, theyd be somewhere between forty and sixty. But I didnt need numbers to know that just as Stephan Wilkinson wasnt old when he became impotent at sixty, Marek Fuchs wasnt young when he had a vasectomy at thirty-six.

It used to be that we had few expectations of sex in middle age. Now, the bar is set pretty high. In popular culture today, midlife sex is hot, hot, hotand women are getting as much as men. Weve got the Desperate Housewives, who have never been desperate a day in their lives, and the Sex and the City girls, with their million-dollar shoes and their unbridled passion. These new icons are buff and beautifuland the fact that they are played by buff, beautiful middle-aged actresses makes them somehow plausible. Most of us, however, neither look like that nor live like that.

The idea for this book came innocently enough when a friend made a confession at dinner one night. He often said things to get a rise out of my husband and me all right, just me. But as we lingered over mussels and fries, he blurted out something that took us all by surprise: Hes hot for middle-aged women. Suddenly, he finds themus?to be incredibly alluring. (I assumed this included his wife, who was sitting right next to him, but that wasnt clear.) He even slows down at the school-bus stop to check out the moms, wondering, and I quote, what their lives are like and what theyre thinking about.

The idea for this book came innocently enough when a friend made a confession at dinner one night. He often said things to get a rise out of my husband and me all right, just me. But as we lingered over mussels and fries, he blurted out something that took us all by surprise: Hes hot for middle-aged women. Suddenly, he finds themus?to be incredibly alluring. (I assumed this included his wife, who was sitting right next to him, but that wasnt clear.) He even slows down at the school-bus stop to check out the moms, wondering, and I quote, what their lives are like and what theyre thinking about.