ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

F ew activities are performed singularly, and the writing of a cookbook is no exception. In this venture, Joanne Ness assumed the major task of developing and testing the recipes. From its very inception, friends and family of both the authors have generously offered their most treasured secrets (thanks, Mom and Aunt Evelyn). A collective thanks to PJC friends. Special gratitude is extended to Sharon Altschuler, Sara Kaufman, Nancy Levin, Bina Rubanowitz, Ellene Newman, Ira and Dorothea Stokes. Thanks, too, to Barbara Turro, who painstakingly calculated the milligrams of calcium and calories for each recipe, and to Emily Paulsen and Gerald Subak-Sharpe, who attended to the many details necessary in producing a book.

Our children, Jordan Ness and David, Sarah and Hope Subak-Sharpe, are commended for their taste-testing and sheer enthusiasm.

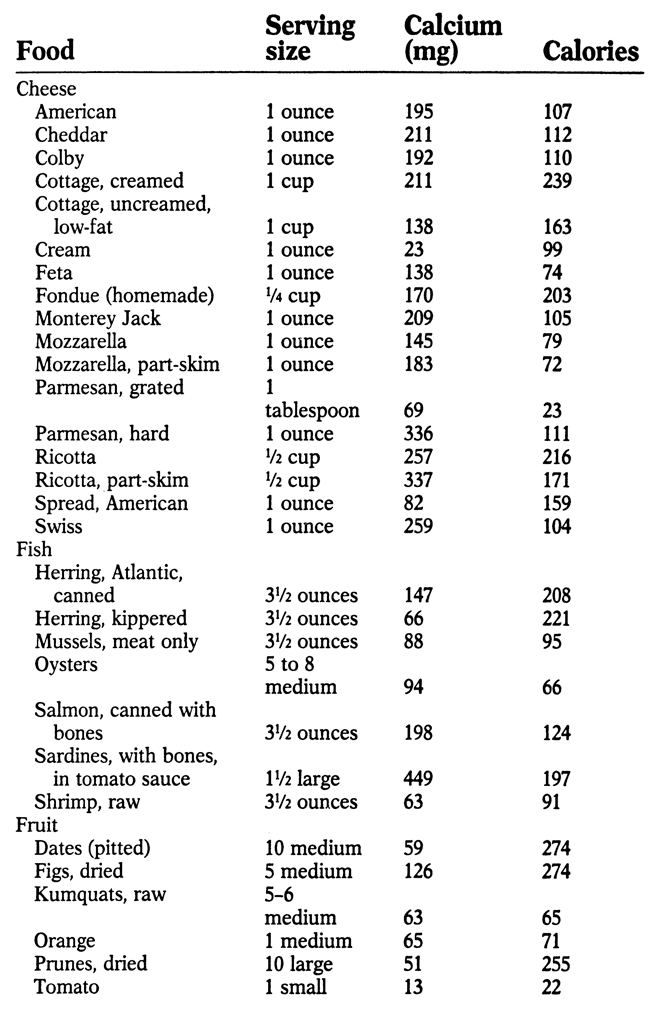

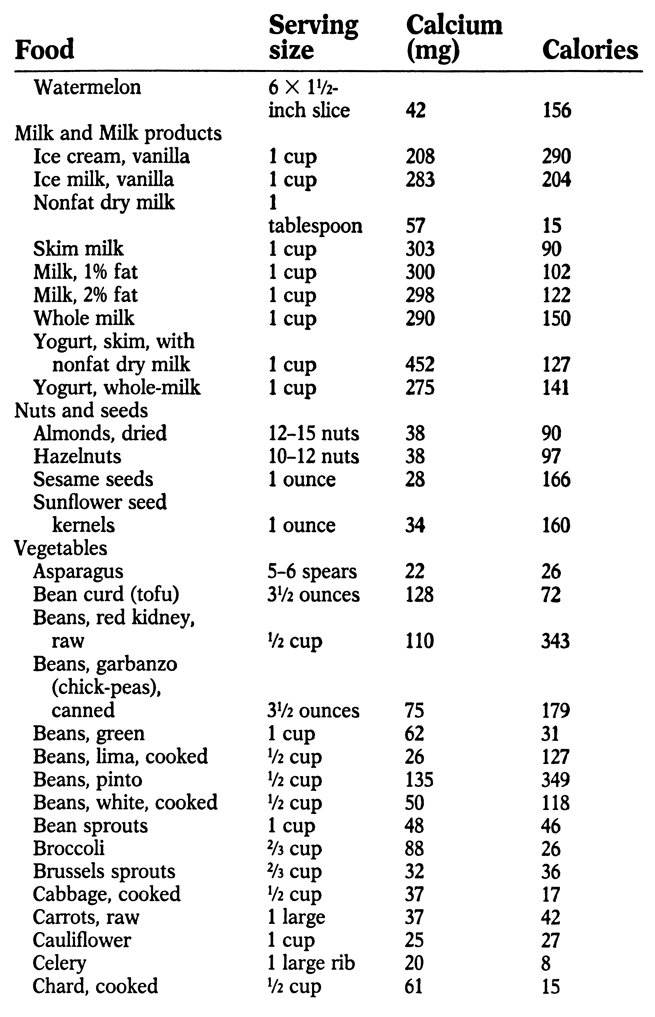

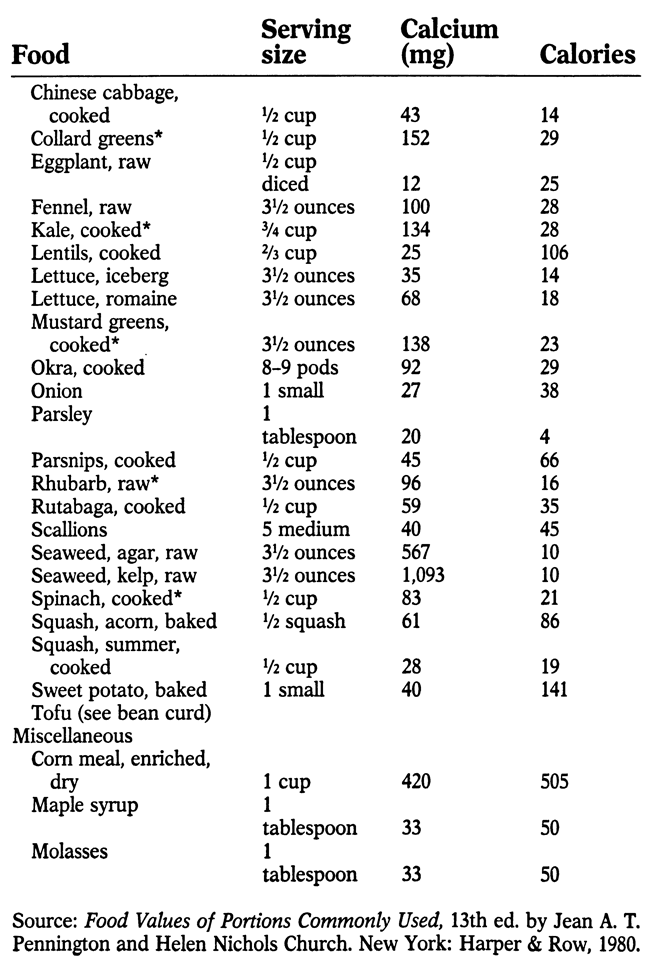

APPENDIX: SOURCES OF CALCIUM

M ost foods contain at least small amounts of calcium. The following list indicates the best sources, along with calories per serving. An asterisk (*) by a food indicates that it contains oxalic acid, which hinders calcium absorption

THE CASE FOR CALCIUM

N utritionists often refer to calcium as the most important of the minerals necessary to sustain life. Yet even in this era of increasing nutrition awareness, most American adults consume diets that are woefully deficient in calcium. Many medical researchers are now convinced that calcium deficiency is a major cause of osteoporosisbrittle, porous bonesa disease that is epidemic among American women.

One half of all women eventually develop this serious, debilitating disease. Its complications contribute to up to 75,000 deaths a year, making it one of the most common killers of women over the age of 65. The direct medical costs are $13.8 billion a year and rising. But most experts are now convinced that these tragic statistics could be substantially improved if women increased their calcium intake early in life. Although osteoporosis is the major consequence of long-term calcium deficiency, other common health problems are now being linked to it. Inadequate calcium may also contribute to periodontal diseasethe breakdown in the bony structure supporting the teethwhich is the leading cause of tooth loss in this country.

Research suggests that calcium deficiency also may contribute to high blood pressure, which is the leading cause of strokes and also a major factor in heart attacks and kidney disease. If so many serious, indeed life-threatening problems are linked to inadequate calcium, why has it taken so long to come to public attention? Unfortunately, the results of this chronic calcium deficiency are not immediately apparent, particularly in adults. Children who are deprived of calcium often develop rickets, a softening of the bones, leading to bowed legs and failure to grow normally. In this country, rickets is now a rare disorder because most children consume a diet high in calcium-rich foods, particularly milka food that many adults shun. It may take years for the chronic calcium imbalance to take its toll; typically, weak bones show up in middle age or later, often when it is too late to reverse the damage. Contrary to popular belief, we never outgrow our need for calcium; in fact, a National Institutes of Health consensus statement on osteoporosis recommends that adult women should consume as much calcium as, or more than, the present Recommended Daily Allowance for growing children.

To better appreciate the importance of calcium in the diet, lets briefly review its many functions. Calcium is the most abundant mineral in the body, accounting for about 2 percent of our total weight. The bones and teeth house 99 percent of this calcium; the remaining 1 percent circulates in the blood. Calcium, along with phosphorus, is essential in the building and maintenance of bones and teeth. But every cell in the body also requires minute amounts of calcium in order to function. Without calcium, the nerves cannot properly conduct impulses; muscles, including the heart, cannot contract; the brain will not function; blood will not clot properly.

To insure that each cell in the body has enough calcium, whenever the amount in the blood falls to a certain level, the mineral is released from the bones in a complex process that is still not fully understood. Calcium consumed in the diet is absorbed into the bloodstream from the small intestine. If there is enough calcium circulating in the blood to meet the needs of muscles, nerves, and other soft tissues, some of the excess is stored in the bones and some will be excreted, mostly in the urine, but also in the feces. As with so many other nutrients, the greater the need, the more effective the absorption process. Thus, growing children and pregnant or nursing women, who have the greatest need for large amounts of calcium, make more efficient use of dietary calcium than other people who still require calcium, but not so immediately. Most of us think of the bones as static, solid structures.

In reality, they are constantly undergoing change, with old bone cells being replaced by new. About every five years, the entire skeletal structure is renewed through this constant rebuilding. Bone renewal requires a steady supply of calcium to insure that the new bone is as strong and dense as that being replaced. But since the skeleton serves as a storehouse for the calcium needed by other body tissue, the mineral is constantly moving in and out of the bones. When calcium is released from the bones for use throughout the body, some may eventually be reabsorbed and some will be excreted. Thus, the body constantly requires new calcium from the diet simply to maintain its stores.

Unfortunately, not all of the calcium consumed in foods winds up working in the body because a number of factors affect the bodys ability to absorb it. Vitamin D is essential to the complex process; a hormone derived from it via a mechanism involving the liver and kidneys stimulates intestinal absorption. Lactose, the sugar in milk, enhances calcium uptake. Some researchers also have found that absorption is enhanced by vitamin C, but hindered by a high level of fat in the small intestine, although a small amount of fat seems to increase uptake. Phosphorus, a companion mineral needed by the bones to make them hard, competes with calcium for uptake by the body. Only certain amounts of each mineral will be absorbed from the blood.

A proper balance is maintained if the two minerals are consumed in about equal amounts. When there is an excessive amount of phosphorus, less calcium will be absorbed. Unfortunately, most of us eat less calcium than phosphorus, which is found in such dietary favorites as meat, poultry, fish, and soft drinks. Ironically, some foods that are high in calcium also contain oxalic acid, a substance that hinders calcium absorption. This acid is found in spinach, kale, mustard greens, rhubarb, chocolate, and certain other foods. Even though some of these foods contain large amounts of calcium, not all of it will be absorbed because of the oxalic acid.

Similarly, a substance called phytic acid, which is found mostly in bran, hinders calcium absorption. Large amounts of tea also reduce calcium uptake. Obviously, to get the maximum benefit from the calcium you eat, you must pay attention not only to how much calcium you consume, but also to combinations of foods that might keep your body from using it. The recipes in this cookbook are designed specifically to point you in the right direction. For example, the entrees and other dishes in this book do not contain red meat or poultry. We do not advocate that these foods be eliminated from the diet, but since these foods are high in phosphorus and low in calcium, we have not included them in the book.