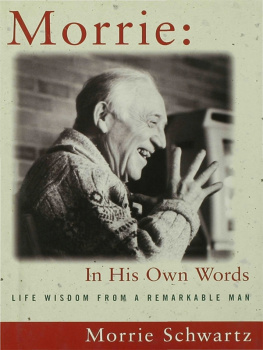

MORRIE

IN HIS OWN

WORDS

Morrie Schwartz

Introduction by Paul Solman

Copyright 1996 by Morris S. Schwartz

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

First published in the United States of America in 1996 by

Walker Publishing Company, Inc.; new hardcover edition

published in 1999.

Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry and Whiteside,

Markham, Ontario L3R 4T8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Schwartz, Morris S.

[Letting go]

Morrie: in his own words/Morrie Schwartz;

introduction by Paul Solman.

p. cm.

Originally published: Letting go/Morrie Schwartz. New York:

Walker and Co., 1996.

eISBN 978-0-802-77749-2

1. Schwartz, Morrie S.Health. 2. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosisPatientsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Terminally illPsychology.

4. Adjustment (Psychology7) I. Title.

RC406.A24S39 1999

362.1'9683dc21

[B] 98-56448

CIP

Book design by Mary Jane DiMassi

Printed in the United States of America

10 9

CONTENTS

His name: Morris Schwartz. "But call me Morrie," he insisted, even to Ted Koppel, who obliged on three Nightline specials in 1995, half-hour interviews which helped make this wise old man a national icon.

Morrie's reason for appearing on network television was as straightforward as the man himself: At age seventy-eight, more fully alive than ever, Morrie was dyingof a degenerative disease known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease. And though actually a rather humble guy, Morrie realized he could use the media for one final accomplishment in an achievement-filled life: to flush death out of the closet, to help people talk openly about illness, decay, and the end we all share.

"Learn how to live," Morrie wrote, "and you'll know how to die; learn how to die, and you'll know how to live." Morrie's message was not only for the sick and those close to them, but for the healthy as well. His was a way of looking at the world, a point of view he expressed on Nightline, in the Boston Globe, and on radio and television nationwide.

And people responded, powerfully. Morrie struck a nerve. Hundreds of viewers, listeners, and readers wrote to himfor advice, for comfort, but most of all to thank him for giving a voice to issues they have been struggling with in silence.

After all, here was a man with a disease that destroys, without exception, the ability of nerves to signal muscles. The muscles stop working and atrophy, in Morrie's case starting with the legs. Then you die.

But Morrie's response to the death sentence was to create a sort of living memorial service. A joyous one. He watched Marx Brothers movies, steeped himself in all the humor he could find. He let friends know he wanted them to visit. And he began writing the aphorisms which form the core of this book.

The book is, in a sense, Morrie's last will and testamentof how to live passionately and calmly, right to the end. As he lost muscle function he handwrote the aphorisms ever more slowly and unsteadily, but with surer and surer conviction. He thought at first they could stand on their own without elaboration. But he came to realize that most readers need help putting them into practice. The aphorisms are written in a sort of how-to shorthand: They're mantras that, by themselves, can seem as formidable as they are profound.

"Grieve and mourn for yourself not once or twice, but again and again," Morrie writes.

But how7? We're not all Morries. Most of us don't know why we should grieve and mourn, don't know how.

And so Morrie began to dictate the biographical commentaries that accompany the aphorismstrying to help teach readers how he'd arrived at the aphorisms, how he meant for people to understand them, and most of all, how to help readers apply the aphorisms and internalize them.

The taping took place over the course of several months and sometimes the effort was enormous. By the end, struggling to cough to bring up phlegm, Morrie could only watch as the microphone slipped off his chest and wait for it to be propped back up. But the more we taped, the more apparent it became that not only were the aphorisms workable, they were part of something much larger. Morrie had a consistent worldview, one that had been evolving for most of his life and that he was only now articulating as a whole. To paraphrase it may sound hokey to some, reassuringly familiar to others. But regardless, to Morrie, life was a process of opening oneself lovinglyto other people, to the world, ultimately, to something larger than ourselves. To the last instant, Morrie was full of wonder and joy. The way he lived his final year was this great teacher's final lesson.

The aphorisms flow from his worldview; the worldview, in turn, from Morrie's biography. And so it helps to know something about him before taking on the text.

A short, freckle-faced redhead, born in Chicago of Russian Jewish immigrants and brought up in the New York ghetto, Morrie "dressed like a schlepper, with half-pants that came to my knees," as he described himself in one of his last interviews. He was, he remembered, "always kind of cheerful, but sad inside." That's because his mother died when he was eight, forcing her son to withdraw into himself.

"I had become aware of vulnerability," he said, "that something precious could be snatched away at any moment."

Growing up motherless sensitized Morrie to loss and his need for other people. A nurturing stepmother who adored both Morrie and his younger brother instilled a compassion for others, combined with a passion for learning.

Morrie made it to New York's tuition-free City College. Turned down for military service in World War II because of a punctured eardrum, he decided to apply to graduate school. He was torn between sociology7 and psychology.

"I'd always been interested in psychology," Morrie said. "What tipped the scales was that psychology involved working with rats." He wound up studying sociology at the University of Chicago.

Reading the likes of Carl Rogers, Harry Stack Sullivan, and Martin Buber, Morrie responded to their philosophy: open yourself up to what you're really feeling. The emphasis wasn't solely on the individual, as psychology would have it, or strictly on society, as the word "sociology" suggests. Instead, Morrie was drawn to the connection between the two: an emerging field known as social psychology.

With Morrie's first job came his first epiphany, because in order to work on a research project at a mental hospital, he had to undergo psychoanalysis.

"I started to understand the full impact of my mother's death... and mourn my loss," he said in his last interview. Morrie described therapy as "cathartic"; it was his first experience with seeing himself at a distance, becoming a witness to himself. As the aphorisms make clear, this became a key technique for coping with his death.