ii

russell c. leong

david k. yoo

Series Editors

2020 University of Hawaii Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Balance, Christine Bacareza, editor. | Burns, Lucy Mae San Pablo, editor.

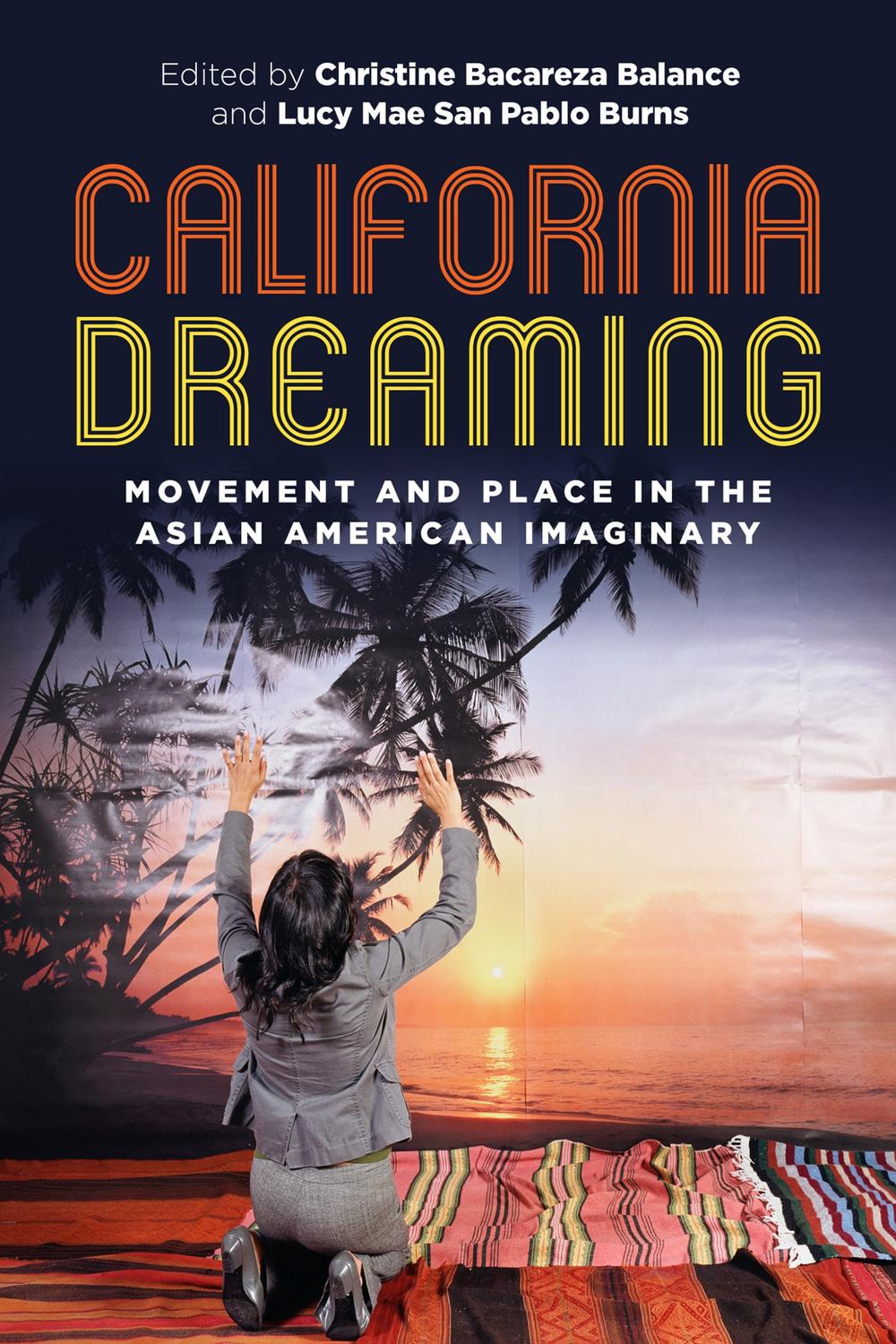

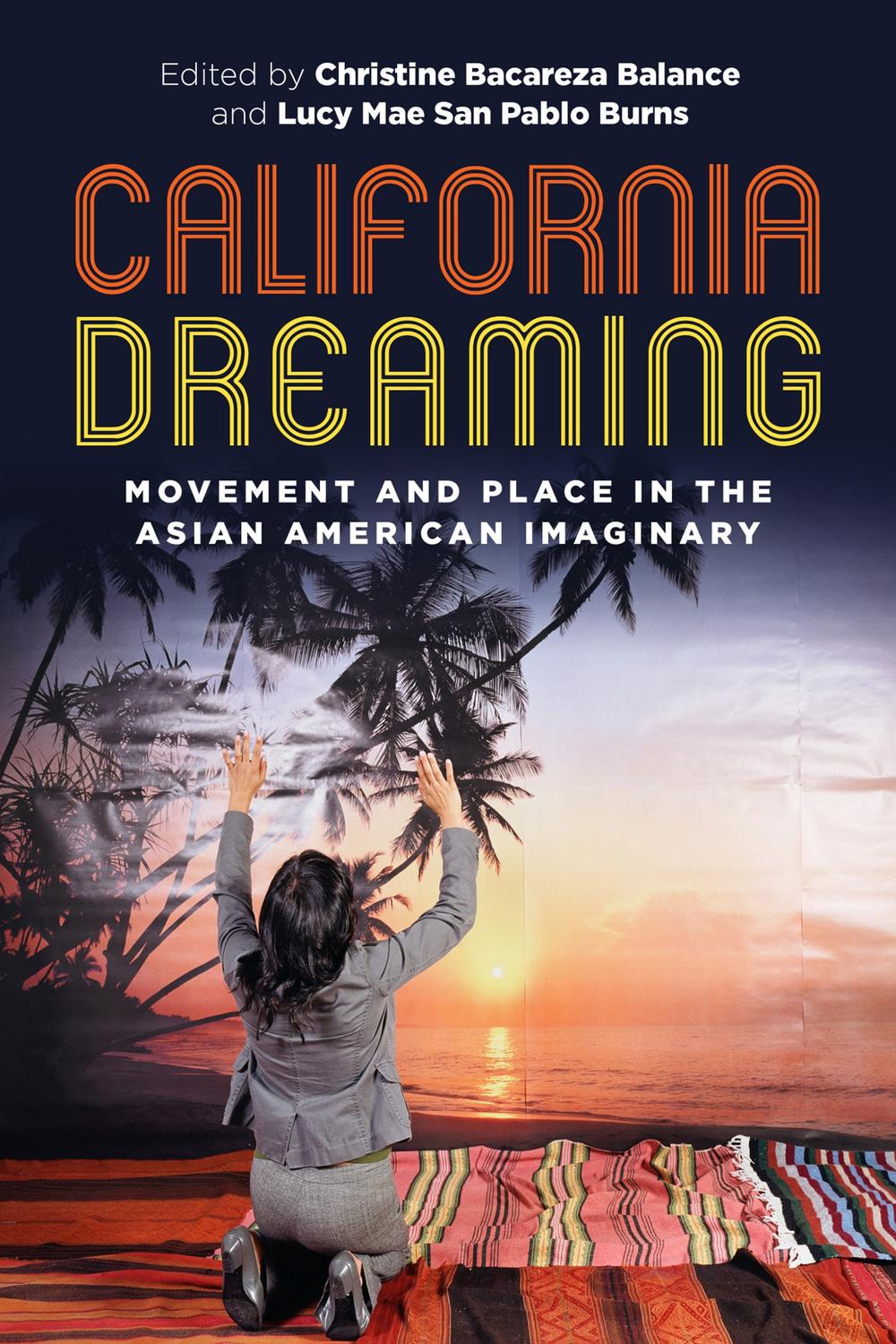

Title: California dreaming : movement and place in the Asian American imaginary / edited by Christine Bacareza Balance, Lucy Mae San Pablo Burns.

Other titles: Intersections (Honolulu, Hawaii)

Description: Honolulu : University of Hawaii Press ; Los Angeles : in association with UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 2020. | Series: Intersections: Asian and Pacific American transcultural studies | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020022874 | ISBN 9780824872069 (cloth) | ISBN 9780824883546 (pdf) | ISBN 9780824883553 (epub) | ISBN 9780824883560 (kindle edition)

Subjects: LCSH: American literatureAsian American authors. | American literature21st century. | CaliforniaIn literature.

Classification: LCC PS508.A8 C35 2020 | DDC 810.9/895073dc2 3

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020022874

Partial support provided by the Arthur C. and Molly Phelps Bean Faculty Fellowship in Performing & Media Arts (Cornell University).

Cover art: Rapture by Gina Osterloh from Somewhere Tropical series (2006). Courtesy of the artist.

University of Hawaii Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources.

- California Dreaming: An Introduction

Christine Bacareza Balance - Sensual Labor of Claiming Place

Nayan Shah - Bohulano Family Binangkal

Dawn Bohulano Mabalon - 100 Tiki Notes

Dan Taulapapa McMullin - Cambodian Classical Dance: Unsettlement, Authenticity, Affect, and Exclusion

Tiffany Lytle - Lao Fighters/Refugee Nation

Leilani Chan and Ova Saopeng (TeAda Productions) - 21 Reasons Why This Movie Sucks

Prince Gomolvilas - From the Island of Berkeley: Hawaiian Belonging in California

Kevin Fellezs - Somewhere Tropical

Gina Osterloh - Dreamers: A Dialogue on Education Rights and the Movement for Undocumented Migrants

Raymundo M. Hernandez-Lopez and Tracy Lachica Buenavista - vi

- Claiming Malibu: Indian Diasporic Dancing Bodies Aligning Geographies across Time and Space

Priya Srinivasan - Oh, Angelita Garcia!

Jason Magabo Perez - Moving Tradition: Alleluia Panis and Kularts

Joyce Lu - Tips for Bus Riding in Los Angeles (excerpted from Going Green the Wong Way)

Kristina Wong - Reels

Larry Padua - Vacuuming Dreams

Lucy MSP Burns - L.A. Dreaming in Taipei

San San Kwan - Poems

Mai Der Vang - Parents Fairytale: Excerpt from Self (The Remix)

Robert Farid Karimi - Traveling Subjects and the Subject of Travel in Vietnamese Diasporic Films

Lan Duong - Photographs from Live and Online Performances

Philip Huang - Abstraction 2: Television Sitcom from DentalOptics

Karen Tei Yamashita - Generations Within: Los Angeles 1992 and South Korean 8008

Yong Soon Min - Golden States of Mind: Cambodian and Vietnamese Artistic Organizing in Southern California and Southeast Asia

Vit L - vii

- Excerpts from DFunQT

DLo - Of Railroads, Camps, and Strip Malls: Symbolic Landscapes of the San Gabriel Valley

Wendy Cheng - Where Youve Been: An Epilogue

Lucy MSP Burns - viii

An Introduction

C HRISTINE B ACAREZA B ALANCE

S INCE 1893, THE FRONTIER MENTALITY has overwhelmingly figured our visions of the American West. In his canonical essay The Significance of the Frontier in American History, Frederick Jackson Turner argued that the frontier was a place where an essential American character was forged. This character, the rugged individual who conquers the elements of an unforgiving landscape and an otherwise lawless society, was predicated upon and helped further a mindset of human superiority. Turner argued that, rather than being affected by the presence and actions of humans, nature simply functioned as provider of unlimited resources. Rather than regard Native peoples, already living in the West, as equals, the frontier individual viewed them as another aspect of the natural landscape to be tamed.

Yet, the frontier mentality also informed much of the U.S. exceptionalist discourse that fueled the nations empire-building project overseasthe moral and ethical need to civilize and tame the wilderness and its primitive inhabitants, vis--vis an Edenic discourse, the desire of U.S. business and government to tap natural resources in systemic ways otherwise unrealized by locals and/or previous settlers. Military and colonial tactics used in seizing and settling Native lands in the western United States were also used in the seizure and settling of lands in the Pacific and Caribbean. Frontier states, like California, provided the training grounds for U.S. war and empire overseas. Many parts of the Golden State, most notably Fort Mason in San Francisco, served as the training grounds and last points of departure for soldiers shipped off to war in the Philippines and other parts of Asia.

At the end of the twentieth century, almost one hundred years after Turners writing, Asian American studies scholars tuned into these intertwined local and global histories. By doing so, they recalled the origins of Asian American Studies as operating within both a domestic context and a transnational imaginary.

Within the frontier imaginary, California promised a land of opportunity for all people. But the length and extent of that opportunity depended much upon ones legal status, ability to own property, and capability of laying claim to the fruits of ones labor. As it operates within Asian American studies scholarship, the frontier mentality also calls to mind histories of those first waves of male migrant laborersChinese railroad workers, Filipino stoop laborers, and Sikh farm workers. As much as the untouched land was there for humans to toil upon, it was capital and companies who hired the men to do such work.

For an Asian American studies that subsists on a particular narrative of immigration and assimilation, Campomanes argues, California looms large as a mythical destination and a congeries of settlements. Which particular narrative we reference, however, is crucial, for one particular narrative of immigration and assimilation actually depends upon a type of disassociation from or counter-identification with such congeries of settlements. Within this logic, even Asian Americans can function as settler colonists.

For certain scholars, frontierism also invokes a field logic of Californias dominance, one predicated upon the notion that, fundamentally, where the communities are, Asian American studies ought to bloom. With its overwhelming number of Asian Americans, a fact somehow signifying various forms of diversity (ethnic, generational, economic) simply by demographic presence, California has been figured as the frontier (or perhaps more fittingly the haven) of Asian American culture and, by extension, of Asian American studies. In this logic, California serves as a place of possibility and site of opportunity as well as an upper limit of achievement. This frontierist logic of Californias dominance has also depended upon certain historical and institutional claimsthe ways in which it has functioned as the fount of the fields origin stories, people, and places; the longevity and spread of established Asian American studies departments and programs within higher education (and even at the secondary and elementary school levels); and these departments and programs proximity to historical sites and contemporary communities. Due to these temporal and geographical reasons, many have argued that Asian American studies in California, unwittingly or not, has set the terms of reference, the political and intellectual norms, for East of California Asian American studies and its assertions.