THE ALASKA

BUSH PILOT

CHRONICLES

M ORE ADVENTURES

AND MISADVENTURES

FROM THE BIG EMPTY

by Mort D. Mason

Voyageur Press

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I happily acknowledge my wifes unfailing support, encouragement, and inexhaustible proofreading efforts, often carried to the point that her gorgeous blue eyes were about to fall out.

I would be remiss if I didnt acknowledge the ministrations and guidance of Michael Dregni, my publishers Number One, who encouraged this sequel to Flying the Alaska Wild even before pencil was first put to paper on it; and to my forever patient, encouraging, and most helpful favorite editor, Kari Cornell, without whom I would truly be lost.

I want to give special thanks to Jules Tepper, incredible outback pilot in New Zealand, for having allowed me to include two of his white-knuckle flights between the covers of this book. Thanks, too, must go to Eric Dorondo, for letting me include in this book the tale of his very, very short flight in a loaded Cessna 150. My profound gratitude for his contribution to this book has to go to Phil, whose last name must forever remain unspoken, as he wishes to avoid the ribbing of his fellow pilots.

Finally, my sincere thanks go to Todd Rust, who carries on the fine Alaska outback flying tradition of his father, Hank, for allowing our use of some of his great color photographs.

D EDICATION

To the memory of my parents, Donald and Irene Mason, who successfully ushered me through my childhood and teenage years, probably with no little exasperationand to my wife, Peggy, who has successfully ushered me through the last few decades of my adult life, clearly with a plethora of justified exasperation. To my children, who suffered through decades of their fathers flying. With great sadness, to the memory of Andrew J. Bear Piekarski, rugged outdoorsman, lodge owner, and frequent flying companion, taken in his prime by one careless moment and Alaskas unforgiving elements. Finally, to all the superb pilots of the QB, those gone west as well as those still with us, almost all of whom were, and are, better pilots than IBurro.

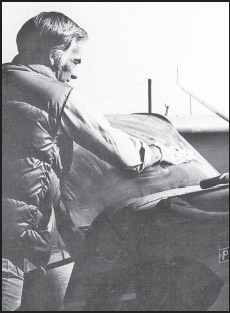

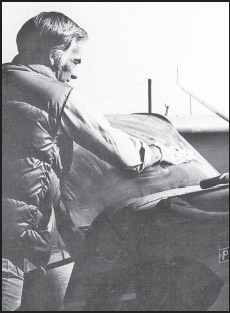

The author carefully cleans the windshield of his Bigfoot Super Cub. A special cleaning agent is used to prevent scratching of the soft Plexiglas windshielda scratched windshield would make landing on tight bush strips and into the morning or afternoon sun extremely hazardous. Photo by John Erskine, Anchorage, Alaska

Introduction

I F YOURE NOT LIVING ON THE EDGE,

YOURE TAKING UP TOO MUCH ROOM.

I should admit to you here and now that I never was a real crackerjack airplane driver. I did pay a lot of attention to preventive maintenance, though. You might say that I was very careful about it. On the other hand, you could say I was scared to death that something bad might happen while I was way up there off the ground. Either way, I paid close attention to the maintenance part of flying on the edge. And while it cost me a few bucks along the way, Ive never cried over money spent for good maintenance. Notice that I said good maintenance.

I wasnt a natural pilot, either, and there werent a lot of good flying instruction books around in those days. At the time that I took the written portion of the private pilots exam, there were only about fifty simple questionsprimarily having to do with stuff like light-gun signals from the control tower, or those flashing beacons once used for nighttime cross-country flying that are, for the most part, no longer available. I took my written exam during a short lunch break from my daytime job at Chugach Electric, the local Rural Electrification Association (REA), in Anchorage, Alaska.

The flight portion of that test was a different bucket of worms in those days, too. For example, full stalls, spins, and serious forward- and side-slips were required back then. The budding pilot could be a little sloppy and get away with it, though. A two-turn spin in each direction was required, but the aspiring airman had only to come out within ten degrees of a predetermined heading in order to pass his or her private pilot flight exam with flying colors. We knew that spins to the left were more easily accomplished, and more accurately stopped, than were spins to the right, but most of us had practiced enough of them to be at least ten-degrees accurate in either direction. And, most of us thought spins were funthey were and they still are.

To give you an example of how far my own ground training and book study went, I had only started my first climbing turn after takeoff during my private pilot flight test when my examiner asked what I thought the rudder was used for, and I replied that it helped to turn the airplane. His response was, Take me back!

He was patient, though, and he must have taken some pity on me, for he allowed me to complete the test. He did, however, hasten to tell me that the rudder was put back there to overcome the drag created by the ailerons when the pilot raised or lowered a wing to begin a turn. Or at any other time a pilot changed the position of an aileron, for that matter.

I had some trouble, too, in trying to understand that power controlled altitude rather than air speed, and that the stick controlled air speed rather than altitude. Hell, I could see that someone had it all backward: the power controlled air speed and the elevators controlled altitude, clearly.

My touch-and-gos were satisfactory to him, but my stalls just about scared him shitless! I had determined that the best way to pass this flight test was to be positive with all my control inputs. So, when the examiner finally asked me for a power-on stall, I just pulled the nose upw-a-a-a-y upand waited for the coming shudder and falloff.

He took the airplane away from me and shouted that I had just scared him out of ten years growth! Gimme the airplane, he said. By then I was shuddering like skis on rough ice.

He pulled the little beast up into a full hammerhead stall, which scared the hell out of me! He proceeded to enlighten me about the joys of tail slides and their guaranteed come-apart results on little fabric-covered airplanes such as the 65-horsepower Aeronca Champion in which we were then staggering and flapping along. By the time he was finished with that little explanation, I was shaking like a sled dog passing peach pits.

My forward slips and side-slips helped save my bacon that day, I think. I could ace those maneuvers all day long, regardless of aircraft type, load, or wind conditions. And I had practiced so many spins by that time that I could easily stop onein either directionwithin five degrees of a predetermined heading, and in almost any kind of light aircraft, with or without turbulence or heavy winds.

My emergency landing techniques were pretty good, too. I have to say, though, that these techniques were carried to the extreme in those days in Alaska, and almost any kid with more than four hours dual instruction could safely dead-stick a light aircraft to a safe landing almost anywhere he or she wanted to put it. We didnt know anything at all about radio procedures, but we could sure as hell fly airplanes! Anyway, I got my ticket that day, and by the time I had completed that check ride, I had learned more about flying than in all my previous hours of dual and solo flight put together.

You should probably know that things were much different in many ways, in those interim days of flying. We werent far beyond the days of the rugged airmail pilots and their barnstorming brethren. This was especially true of flying in Alaska. There were almost no tricycle-geared airplanes there, probably because there were so very few airports or airstrips. We sort of grew up on sandbars, beaches, and gravel bars. The bolder ones among us also used mountain ridges or slopes, glaciers, and, if the tires were big enough, even the tundra. Except for the more expensive light aircraft, radios were a rarity. For that reason, most light aircraft in Alaska didnt have generators and, as a result, few had starters. Most were hand-propped, an art that seems pretty much lost today. A few aircraft boasted exterior wind-driven generators, but these were considered by many to be too dangerous to be worth the risk. Should the rapidly spinning little propeller ever get loose, it could cut through the cockpit of a small airplane like a knife through hot butter. Almost everything we knew about light aircraft flying was different, I guess.

Next page