For Gudanji

This is for you so you know

why your feet walk the path they do

why your eyes seek the shadows

why your ears hear the stories running in the air

whispering tastes into your mouth to then

nourish your body.

This is for you so you will know the stories

when they walk with you

and talk in their many voices

so, listen with all of who you are and feel this story

running through your body

taking you into country.

Mankujba!

Dedication

This is for Maxine and Lurick Sowden,

my mum and my dad,

who taught me the biggest lessons in life,

and for my grandmother, Pbirrianjulunga,

who made everything possible.

Preface

Much of this book was written on Country. My husband and I took a tent and swag, a mosquito net, camping table and chairs and a small generator to keep my camera and laptop powered. Like me, my son understands the true luxury of hot water and so he wired together some kind of circuit that I would attach to a spare troopie battery in order to have a hot shower.

In the early mornings, while a little black and white bird danced at my feet as I wrote, Rick cooked mudjiga, the freshwater crayfish from our creek, for our breakfast. In the cooler times of the afternoons we walked the paths that my family have most recently walked as our children have grown, but which Gudanji have been walking for thousands of years. We caught bream and barramundi for dinner and went to sleep under the sky, watching the phases of the moon shift and control the light of the stars.

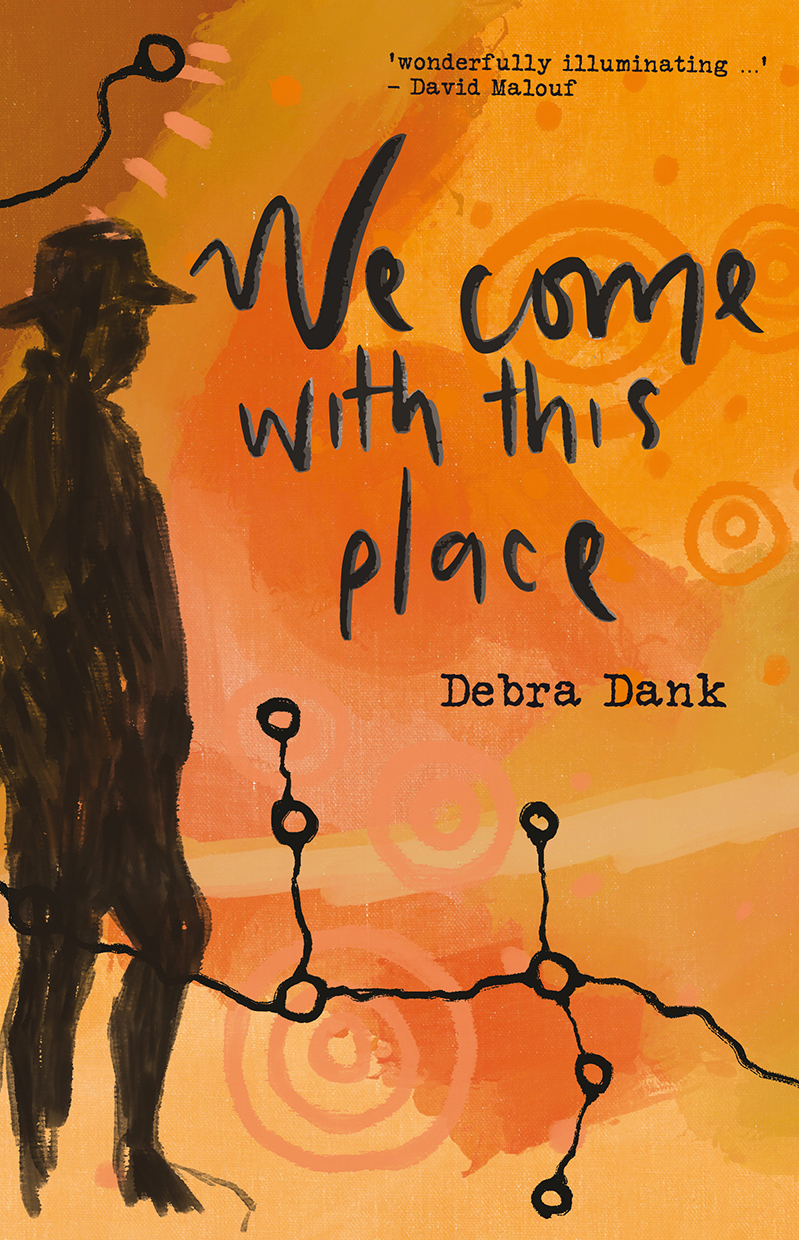

We Come with This Place is, perhaps, a strange kind of letter, written to my place a recalling of events and activities that I and my family have experienced, in order to tell Garranjini that I remember, and I know. It is all based on real events. Some parts have been reimagined, because they happened outside my presence, and several names have been changed. Our relationship with our place, however, is genuine and lives in ways that are not easily told in English words or western ways. This book began its life as part of my PhD study. I wanted to show how story works in my community and how it has contributed to our living with country for so long. It seemed to me imperative to talk about those voices, both human and non-human, who guided Gudanji for centuries before anyone else stepped onto this land.

Note

Like all languages, those used in the south-western Gulf of Carpentaria share, borrow and mix vocabulary from multiple language groups. The words from different languages used in this narrative are included here in the ways they are currently used within my family. The peoples and languages mentioned include Garawa (people of the Northern Territory Gulf Country east side of Borroloola approximately to the Queensland border area), Gudanji (people of the north-eastern Barkly Tableland area), Kalkadoon (people of the Mount Isa area), Wakaja (people of the southern Barkly Tableland area from the Territory and towards the Camooweal area), Wombaya (people of the central west Barkly Tableland area) and Yanyuwa (people of the Northern Territory Gulf Country specifically the islands off the coast from Borroloola and including Borroloola).

They are all part of my family, extended and otherwise, and I offer my gratitude and respect for their role in keeping the stories.

Foreword

Dr Tyson Yunkaporta

There are some things I just cant face, but they eat away at my insides like worms. In that regard, Im very much the same as most people living on this continent. I avoid content about the horrors of our occupation and gradual genocide as Indigenous people. I havent dealt with the throughline of history from the savagery of the frontier wars to the interventionist policies of today.

We are our stories. Spending time with this book is like spending time with Debra Dank herself. Shes like the grannies we remember who fought battles with sticks and drew nourishment and medicine from land and waters to animate our flesh. She hurts us, digs bullets out of old wounds that never healed properly, sucks out the poison and then begins our healing with love and laughter. She does this for everybody, no matter which side of the rifle youre on.

I used to know the places Debra is writing about, and I still have the thick scars on my scalp from that time when I was a little bub. I had almost forgotten about those sticks and stones, but now they burn me again and I swear I can feel the blood running down my face. But thats just hot tears that keep coming around every time I think about Debras grandmother and what was done.

But then theres her unconditional love running through every page, and it helps a little, but not half as much as the laughter. Deb as a princess in the school play was a story that made me laugh my cheeks off, made me laugh until I cried clean tears that fell like rain after a long drought.

I had been avoiding having that good, hard cry, but I think I really needed it.

Dont you?

Contents

Prologue: Of souls and stories

One day, a long way from home, inside the Oxford University library, when the wind outside blew bitterly cold and drizzly rain fell upon those who scurried to find shelter, I carefully breathed in the dust from a 400-year-old edition of Aristotles De Anima On the Soul. I thought that book with its fragile leather jacket was too treasured and precious for even the touch of the white gloves worn by the librarian. I tried to imagine him, Aristotle, in 350 BCE, sitting and writing the words, thinking how to record the story of souls, but I could only wonder as vague images tried to speak to me through dust motes rising from the thick pale pages. It is not easy to record the story of souls.

Our Gudanji kujiga grew here with Gudanji Country about the same time as our stories, and it was long before paper and words learned to yarn together. I dont know how our mob knew about souls, just that they did, because our stories and our kujiga live inside each other, as well as out there across our country, and inside our bodies. Those stories and our kujiga find their way then, through the black and red soil of this earth, to the goodalu within us, in moments when we know to listen to our heart. Our story comes from this country, but it does not often experience the hospitality of classrooms, libraries or bookstores.

I know because Ive been in those places. I sat in the classrooms of schools in Queensland in the 1960s and 1970s and have stood in front of them, and in other places of western learning, since the 1980s, but our soul-deep stories are rarely located in those establishments. It is mainly other stories that occupy their bookshelves, told in voices that have grown in other places, voices that are new to this place and are yet to learn this country. Our stories are mostly not there; they are located somewhere that is silent and hidden, in memory that is not often visited. Some of those new voices try to tell our story but their souls do not speak the language of this place and their ears are yet to learn to hear its stories.

Like our kujiga, this black soil, red dirt and these dry brown hills and fresh water tell tales that are little parts of a big story. Many voices tell our story because we do not exist here alone, nor do we walk here without the sacrifice of others imagine the terror and the sorrow of that kind of lone story. Imagine the sorrow of living without obligation and without reciprocity in a solitary story. So this is not a story about me, rather it is about Gudanji being, becoming and continuing.

Our story is etched into the rocks and it whispers through the trees and with our kin who are more than human. The wind tells it, sometimes strolling gently, sometimes bellowing from cavernous, dark, felt places, where eyes do not see, and only our goodalu can feel. Our stories are the memories that scratch and gnaw as we walk, and we rub shoulders with the past, but mostly our stories travel with those big freshwater rivers, always looking to find their way back to the birthing salt water but still nurturing us as we bend and drink from those same waters. Some of our tangible story can be told in words; and someday, some of it might be warmed by a soft leather book cover and beautiful marbled endpapers, like the books in the Oxford library, but it will not be our full story because that is too big for words and paper and pages. It lives with our Country.