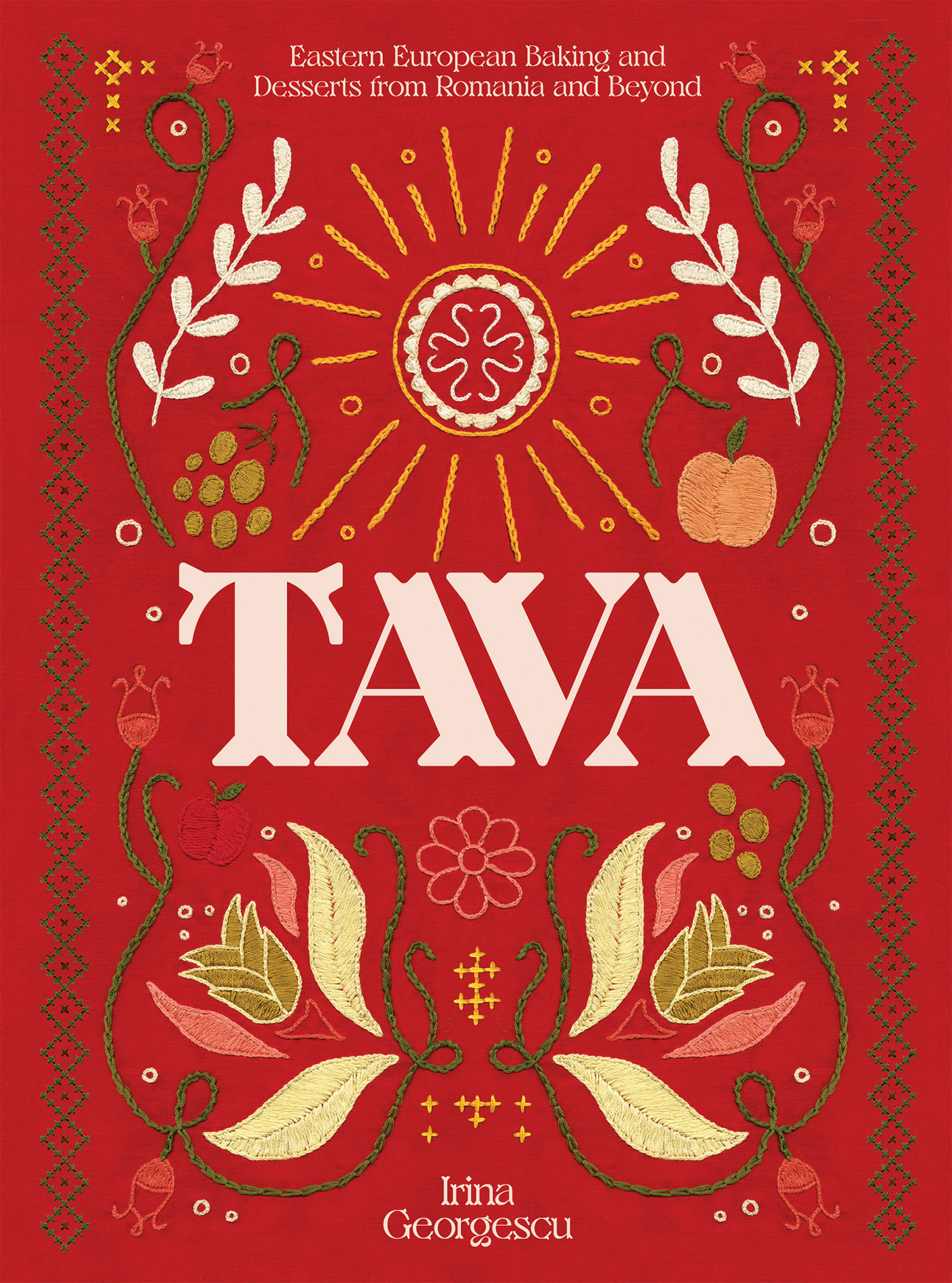

I am such a huge admirer of Irina Georgescu in general, and of this extraordinarily impressive and important book in particular. A must-have, not just for enquiring bakers, but crucially for all those interested in the context and evolution of culinary culture.

Nigella Lawson

A joy and an education. Irina Georgescu has disentangled the strands woven into Romanian cooking and identity and she has done so deliciously, through glorious cakes, pies, strudels and doughnuts. Cook, eat, learn.

Diana Henry

A constellation of cultures

How we bake in Eastern Europe, and especially in Romania, is largely unknown. My aim in writing this book is to share the stories of those who prepare the dishes that have come to form our national cuisine. These pages contain recipes that speak of the identity of these communities and specific regions across the country. No small task, given that Romania is a constellation of cultures a little Europe, where the Middle East meets Austrian and German influences, layered on top of the inheritance left by the ancient Romans and Greeks. This book is about centuries of diversity and overlapping cultures, from which Romanian cuisine has emerged in all its rich flavours and textures.

I have chosen to focus on just six cultural communities (although there are many more that live in the region) and share their traditions and history through their iconic baking recipes. I couldnt have written a cookery book without this broader context, while still allowing the recipes to take centre stage. You will find Armenian pakhlava, Saxon plum pies, Swabian poppy-seed crescents, Jewish fritters and Hungarian langoi alongside plcinte pies, alivenci corn cake, strudel and fruit dumplings. Rice or pearl barley puddings, doughnuts and gingerbread biscuits come with their own stories, while chocolate mousses, meringues in custard sauce and coffee ice cream introduce you to the glamour of famous Eastern European pastry shops.

I hope that these recipes will pique your interest and tempt you to embrace the unfamiliar as much as the familiar. Certainly, you will love the comforting and homely feel of all the dishes.

The idea of national cuisine

Romanian cuisine has been influenced over the years by the countrys remarkable location within Europe and its impressive topography, dominated by the Carpathian mountains, the Black Sea and the mighty rivers including the Danube, which created regions of flourishing trade with different historical dynamics.

For centuries, the country we know today as Romania was comprised of three main regions: Wallachia in the south, Moldavia in the east and Transylvania, including the neighbouring county Banat, in the centre. The first two were united in 1859, when they freed themselves from the Ottoman Empire and Russian protectorate, while Transylvania and Banat joined in 1918 after the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This is how the cuisines of two empires became part of our national cuisine.

The Republic of Moldova formed later, in 1940, from the historic Romanian principality of Moldavia. It existed for a while as part of the Soviet Union and gained independence only in 1991, retaining Romanian as the official language. In Romania, we refer to both the Republic and the region of Romania by the same name: Moldova.

The first cookbook to use the term Romanian, implying a national cuisine, was published in 1865, soon after the first two Romanian principalities had united. The recipes in Buctria romn had been collected by Christ Ionnin from friends, chefs, merchants and intellectuals, and offered a glimpse into what people ate and how they cooked in this newly formed territory. Most of the book reflects a cuisine of the middle classes, strongly influenced by 17th18th-century western Europe, and is only dotted with Ottoman dishes. It proved how European and how well connected to the Western gastronomic world this new country already was. Ice creams, set creams and souffls featured heavily in the book, as did puddings involving bread or crushed biscuits cooked with milk, or using bone marrow, almonds and dried fruit, under the name of turte or torte. Both names described either savoury round flatbreads, or round cakes and puddings. The book also mentioned a variety of doughnuts fruit dipped in batter then fried; poached fruit such as compotes; magiun or povidl plum butter and, not surprisingly, revani Turkish semolina cake.

I find it is difficult to draw a portrait of Romanian cuisine in hard lines it is more about smooth shading and blending. The many communities here German, Hungarian, Armenian, Jewish, Turkish, Greek, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Serbian, Czech, and even French and Italian brought layer upon layer of influences into Romanian kitchens, which often overlap. Some of these groups were historically prominent and generated various written sources in their own languages, which has made it difficult to trace back or claim any Romanian provenance to dishes.

Any attempt to profile the concept of Romanian cuisine, sooner or later, hits the vast wall of the Communist regime. Firstly, the massive import of recipes from Western cookery books contributed to the abandonment of many of our regional, characterful foods. The imports were meant to prove that working men and women of a classless society had access to sophisticated foods. Yet it eventually led to a culinary mismatch.

Secondly, in an attempt to bring in hard currency from the western markets through tourism, the regime introduced terms to romanticise the provenance of dishes: recipes would be described as shepherds this, or hunters that; we see hut cake (the latter a copy of a royal cake called Caraiman), haiduc grilled chops (haiduci were outlaws, like Robin Hood), or gypsy fillet steak creep in. The regime also standardised cookery books and restaurant menus, and many people today consider those recipes to be traditional and at the core of our national cuisine.

Thirdly, the focus on mono-crops and imports to feed the masses, such as wheat, rice and sunflower (for oil), had a devastating effect on the diversity of our local culinary landscape. It sent many traditional grains and plants into oblivion.

Today, there is a desire to rediscover ingredients and cooking methods from the past, and incorporate them into our modern lives.

An intricate fabric

Throughout this book, you will be able to piece together a social and political landscape of some of the regions in Romania, and the relations between their people. You will find the Szkelys and the Saxons in southeastern Transylvania, defending the border at the feet of the Carpathian mountains with their military skills and fortified churches. You will meet the Magyars, the dominant political power of Transylvania, and read about the Swabians in the Banat region of western Romania. I tell the story of the Armenians thriving in an 18th-century cosmopolitan city, which later became the capital of Romania: Bucharest. I talk about the Jewish communities influencing the commercial landscape of Moldavia and the ports on the Danube river in the east. There are stories about Casa Capa, the iconic pastry shop in Bucharest, and about the Romanian monarchy modernising and uniting the country. The book also encompasses a longer journey from Romania to Hungary and Germany, as the countries have a lot of history in common and, through it, a shared culture, too.

Next page