First published in 1985 by

Kegan Paul International Limited

This edition first published in 2009 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Ayla Esen Algar 1985

Printed and bound in Great Britain

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 10: 0-7103-0524-9 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-0524-4 (pbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

Acknowledgements

My chief debt is to my grandmother, from whom as a little girl I unconsciously acquired a sense of pleasure in offering food as an expression of love. Then I remember with gratitude my mother, my aunts, and all the other members of my family and my friends in Turkey, thanks to whom love, laughter, friendship and company have for me always been intermingled with the smell, color and taste of food. As for my sonsDennis, James, Larry and Selimto them go my thanks for the appreciationsubtle and not so subtlethey have lavished on my food. My husband, whose comprehensive enthusiasm for Turkish cuisine extends even to the drinking of pickle juice at emberlita, has encouraged and helped me in numerous ways.

To Bill Schwob goes my sincere appreciation for the aesthetic sensibility and professional skill he brought to taking the photographs.

Above all, my heartfelt thanks go to Moinuddin Shaikh who not only gave the first impetus to the project but continued, under trying circumstances and at great expense, to support my efforts for its completion.

Finally, many thanks to Hilary Turner, my link with London, for seeing the book through the press.

Ayla Esen Algar

Berkeley, California

July, 1985

Introduction

Eat of the good things We have

provided for you as sustenance.

Quran 2:58

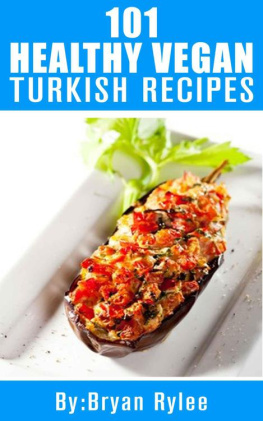

The main claim to interest of any cuisine is, of course, the stimulation it gives to the appetite and the satisfaction it provides to the palate. But food, properly considered, is not a simple matter of preparation and consumption, which are often complex undertakings in themselves; it also touches upon religious prescriptions and customs, aesthetic tastes, geographic and climatic conditions, social stratification and prosperity. The study of food, then, is a proper although generally neglected concern of the historian, and the cuisine of a people may be regarded, in the words of the hero of a nineteenth-century Turkish novel, as a complete civilization in itself.

The integration of food with social, religious, and cultural life was certainly very marked with the Ottoman Turks, and even though the state and civilization they created have crumbled, much of their gastronomical legacy survives in present-day Turkey. To place the delicacies of Turkish cuisine in historical perspective, and to enable the users of this book to supplement the delights of the palate with the pleasures of historical reminiscence, we invite them to peruse this survey of food in Turkish history, orlooked at somewhat differentlyTurkish history in food.

Little is known of the culinary habits of the largely nomadic pre-Islamic Turks who inhabited the eastern and northeastern reaches of Central Asia. It is probable that their diet consisted largely of milk products and meat, and that they did not challenge the rule that elaborate cuisine is a by-product of the settled life. One of the earliest Turkish states, that of the Uyghurs who settled in what is now known as Sinkiang in the eighth century of the Christian era, was heavily influenced by the neighboring civilization of China, and this influence may have extended to matters of food. The name of one Turkish dish, mant (a kind of dumpling; see p. 253), is actually derived from Chinese, and the borrowing presumably took place during this period of close contact with China.

The recorded history of Turkish cuisine begins in about the tenth century, when the Turks came into contact with the Irano-Islamic culture of West Asia and definitively entered the orbit of Islamic religion and civilization. Like other aspects of that civilization, its cuisine was the joint creation of different ethnic elements who borrowed from each other in an uninhibited interchange. Nonetheless, it is possible to assign a definite origin to certain dishes on the basis of etymological or other evidence. Pilav, for example, is originally an Iranian dish (the Turkish word being derived from Persian pulau), although the Turks came to evolve many distinctive rice dishes not found among the Iranians. Other dishes, by contrast, are originally Turkish, and the words designating them in Persian (and sometimes Arabic) are Turkish. Bulgur (cracked wheat; see p. 219), for example, is a Turkish contribution to the culinary stock of the Near Eastern peoples.

Another contribution of the Turks, one much less familiar to us, is tutma. An early Turkish lexicon described it as a well-known Turkish dish;

The name tutma has virtually disappeared from Turkish cuisine, although dishes similar to it are still prepared.

Another part of the pre-Anatolian legacy of Turkish cuisine is the gve, a kind of vegetable stew cooked in an earthenware pot. The original form of the word appears to be kme or gmme, meaning buried; that is, the pot would be buried in hot ashes to cook its contents, a method still used for baking bread in both Central Asia and Anatolia.

One branch of the Turkish peoples settled in Anatolia from the eleventh century onward, and a new and significant period in Turkish history began. Having emerged from the landlocked confines of Central Asia, the Turks were now in a position to have a decisive effect upon the destinies of the Balkans, the Arab world, and much of the Mediterranean basin. Political prominence went hand-in-hand with cultural splendor, so that the Ottoman centuries came to mark the apogee of Turkish history.

It is not surprising, then, that Turkish cuisine attained new heights of elaboration and complexity in the Ottoman period. It came to overshadow fully the cuisine of Central Asia the Western Turks had left behind, a cuisine that was in any event greatly impoverished by the agricultural decay and economic stagnation that resulted from the ravages of the Mongols and their successors. In Anatolia and the Balkans, the Turks gained access to new types of food: fruits and vegetables generally unavailable in Central Asia, olive oil in abundance, and seafood. The dishes concocted using these were combined with fare of Central Asian origin