ALSO BY ALEXANDER WAUGH

TIME GOD FATHERS AND SONS

FOR SALLY

Es gibt eine Unzahl allgemeiner Erfahrungssatze, die uns als

gewib gelten. Dab Einem, dem man den Arm abgehackt ,

er nicht wieder wachst, ist ein solcher.

There are an enormous number of general empirical

propositions that count as certain for us. One such is that

if someone's arm is cut off it will not grow again.--ludwig wittgenstein,

ON CERTAINTY 273, 274

PART ONE

PART TWO

PART THREE

PART FOUR

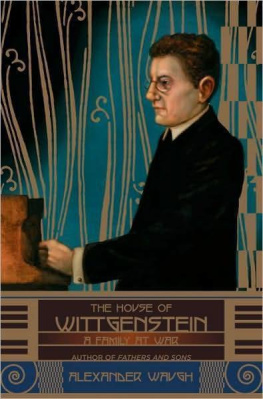

VIENNESE DEBUT

Vienna is described--over-described--as a city of paradox; but for those who do not know this or have never been there, it may be pictured as a capriccio drawn from the flat sound bites of the Austrian Tourist Board, a place defined by its rich cream cakes, Mozart mugs and T-shirts, New Year's waltzes, grand, bestatued buildings, wide streets, old fur-coated women, electric trams, and Lipizzaner stallions. The Vienna of the early twentieth century was not marketed in this way. In those days it was not marketed at all. Maria Hornor Lansdale's once-indispensable guide of 1902 draws a portrait of the Hapsburg capital that is at once grubbier and more dynamic than anything suggested in our modern guidebooks. Her book describes parts of the Innere Stadt or city center as "dark, dirty and gloomy" and of the Jewish quarter she wrote: "The interiors of the houses are unspeakably squalid. As one ascends the stair the rickety banister sticks to one's fingers, and the walls on either side ooze. Entering a small dark room the ceiling is covered with soot and the furniture crowded close together."

A German might step onto a Viennese streetcar and find himself unable to exchange a word with any of his fellow passengers, for the city then was home to a rapidly expanding population of Magyars, Rumanians, Italians, Poles, Serbs, Czechs, Slovenes, Slovaks, Croats, Ruthenians, Dalmatians, Istrians and Bosnians, all of whom lived together apparently in happiness. An American diplomat describing the city in 1898 wrote:

A man who had been but a short time in Vienna, may himself be of pure German stock, but his wife will be Galician or Polish, his cook Bohemian, his children's nurse Dalmatian, his man a Servian, his coachman a Slav, his barber a Magyar, and his son's tutor a Frenchman. A majority of the administration's employees are Zechs, and the Hungarians have most influence in the affairs of the government. No, Vienna is not a German city!

The Viennese were regarded abroad as a good-natured, easygoing, and highly cultured people. By day the middle class congregated in cafes, spending hours in conversation over a single cup of coffee and a glass of water. Here newspapers and magazines were provided in all languages. In the evenings they dressed for dancing, for the opera, the theater or the concert hall. They were fanatical about these entertainments, unforgiving of the poor player who forgot his lines or the singer who sang sharp, while idolizing or deifying their favorites. The Viennese writer Stefan Zweig remembered that passion from his youth: "Whereas in politics, in administration, or in morals, everything went on rather comfortably and one was affably tolerant of all that was slovenly and overlooked many an infringement, in artistic matters there was no pardon; here the honour of the city was at stake."

ON DECEMBER 1, 1913, there was cold sunshine over most of Austria. By the evening a mist had spread from the northern slopes of the Carpathian Mountains down to the rolling hills and verdant lowlands of the Alpine Foreland. In Vienna, the air was still, the streets and pavements quiet and the temperature uncommonly cold. For the twenty-six-year-old Paul Wittgenstein this was a day of high excitement and excruciating tension.

Clammy fingers and cold hands figure in every pianist's worst dream--the slightest sheen from the glands of the pads can cause the fingers to slip or "glitch," accidentally hitting two adjacent keys at once. The sweaty-fingered pianist is slave to his caution. If his hands are too cold, the finger muscles will stiffen. Coldness in the bones does not drive sweat from the skin and in the worst instances the fingers may be immobilized by cold while remaining slippery with sweat. Many concert artists spend a nervous hour or two before a winter recital with their hands plunged into a basin of hot water.

Paul's concert debut was scheduled to start at 7:30 p.m. in the Grosser Musikvereinsaal, a hallowed place, of near perfect acoustic, where Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler heard many of their works performed for the first time. It is from here--the "Golden Hall"--that the famous New Year orgy of waltzes and polkas is annually broadcast to the world. Paul did not expect his debut to sell out. The auditorium had a seating capacity of 1,654, with 300 standing places. It was a Monday night, he was unknown, and the program he had chosen to perform was unfamiliar to the Viennese public. He was, however, well acquainted with techniques for papering a house. As a boy he had been sent by his mother to buy 200 tickets for a concert in which a family friend was playing the violin. The man at the ticket office dismissed him as a tout, shouting in his face: "If it's tickets for resale you're wanting you can go elsewhere!" Paul returned to his mother, begging her to appoint someone else to the task. For the first time in his life he felt ashamed of being rich.

If the hall was going to be half empty, at least those seats that were occupied should be filled with as many allies as possible. He wanted to create an atmosphere that would give the impression of strong public support. The Wittgenstein family was large and well connected. All siblings, cousins, uncles and aunts were expected to attend and to applaud uproariously at the end of each piece regardless of how they felt he had played. Tenants, servants and the servants' distant relations, many of whom had never before attended a concert of serious music, were plied with tickets and summoned to appear. Paul could have hired a smaller hall but was advised that the critics might not show up if he did so. He needed Max Kalbeck of the Neues Wiener Tagblatt and Julius Korngold of the Neue Freie Presse to be there. These were the two most influential music critics in Vienna.

Next page

TIME GOD FATHERS AND SONS

TIME GOD FATHERS AND SONS

VIENNESE DEBUT

VIENNESE DEBUT