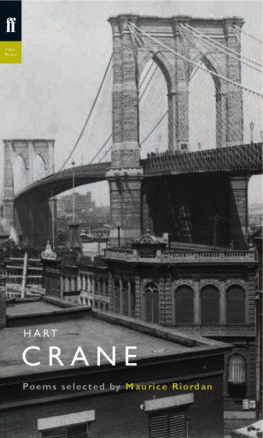

The Life and Times of

Charles R. Crane, 18581939

The Life and Times of

Charles R. Crane, 18581939

American Businessman, Philanthropist, and a Founder of Russian Studies

in America

Norman E. Saul

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth, UK

Published by Lexington Books

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP, United Kingdom

Copyright 2013 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-0-7391-7745-7 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-7391-7746-4 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

List of Figures

Preface and Acknowledgments

During research and writing on Russian-American relations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, I could not avoid encountering Charles R. Crane, who had a deep interest in Russia, as well as a business connection. I soon discovered that he had acquired an appreciation of Russian culture and life through travel in the country, unusual for the son of a Chicago industrialist with little formal education. By these contacts he developed relationships with many prominent Russians in political, cultural, and artistic spheres. Perhaps what intrigued me most was how this man pursued his goal of making Americans more aware and educated about that country and devoted considerable amounts of his own wealth to achieve that goal. More investigation provoked my curiosity into his family and his many political and cultural associations in the United States and abroad. And I soon discovered that he also had made major contributions to American political history.

I began to see this person as a rather remarkable man who devoted his time and much of his financial resources first to his own enlightenment about the world and then to a desire to share that with his fellow citizens through university studies, sponsoring visiting lecturers from many parts of the world, and by subsidizing publications. His dedication to these pursuits spurred my own goal of providing a more detailed accounting of his life and work for posterity, especially as a premier founder of Russian studies in America. Charles Crane was in one way a unique individual in his foresight, imagination, and will power in pursuing his wide range of interests in Eastern and Central Europe, the Far East, and the Near East, but in others he was typical of a generation that led the United States to world power.

Charles Crane made unique contributions that created a record of a man who believed sincerely that Americans should be educated through lectures, university courses, study of foreign languages, and travel for the world they would lead, especially those areas beyond London, Paris, and Berlin, to Russia and Eastern Europe, the Near East, and the Far East. In all of them he left his mark in rather curious ways, as will be related in the text that follows. Above all, he had a particular genius in promoting the best in others, including his family and close friends, but especially among the established political and cultural elite, as well as those who wandered into his vision of what should be done. David Hapgood, his first biographer, had it right: The man who bet on people. And it is quite interesting to see how he did all of this.

Crane is probably best known as a member of the King-Crane Commission that filed a controversial report on the Near East during the peace negotiations in Paris in 1919, but I will show that this difficult task was much more to his credit than appears in many secondary accounts. This was only a small part of his involvements in world affairs that involved an extraordinary amount of travel and investigation from Omsk, Siberia, to Sanaa, Yemen, from Constantinople to Cairo, from Prague to Omsk, from Peking to Calcutta. Few other Americans can challenge his record of ocean crossings sailed, railroad miles logged, camels and mules ridden. This took dedication and endurance especially for one not always in the best of health. And one thing can be counted onalmost always wearing a tie, even at work on his California date ranch.

Another reason for my pursuit of this project is that new materials became available in the Crane Family Papers at Columbia University. These shed much more light on the man and his many missions. I am indebted to several individuals who provided inspiration, advice, and encouragement along the way. First is Thomas Smith Crane, a grandson and collector and supervisor of the Charles Crane Family Papers, following on his fathers foundation of the collection. He encouraged and advised me in this project from the beginning to the end. I have also appreciated the assistance and openness of other members of the Crane family, ranging from grandson David Bradley to great-grandson Joseph (Brad) Bradley, a colleague in Russian history, who I knew long before beginning this endeavor.

Through Tom Crane, I have been fortunate to see many more important papers of his grandfather deposited in the Bakhmeteff Archive (BAR) at Columbia University. This collection, primarily consisting of papers of migr Russians, was established by Boris Bakhmeteff, the Russian Provisional Government ambassador to the United States in 1917 and continuing officially until 1923. After the Bolshevik seizure of power, he became a professor of engineering at Columbia University, which explains the location of the papers. The papers of a number of Americans who were involved with Russia were also included in the collection. The Charles Crane Papers were begun by John Oliver Crane, the younger son of Charles Crane and father of Tom, and consisted of microfilms of typed copies of original papers in the family. He had also successfully collected other papers from family members and at the time (1970s) was residing on the Upper West Side of New York, nor far from Columbia.

The Bakhmeteff Archive (BAR) and the Crane collection in it, have been expertly organized and superintended by its curator of recent years, Tanya Chebotarev, to whom I owe many thanks for her efforts to make unprocessed material available, as well as to her inspiration and encouragement during many weeks spent in the pleasant and collegial facilities of the Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Butler Library. Her special interest in the Crane materials led to her presentation of a report on them at a scholarly conference at Dartmouth in 2008. I have arbitrarily divided the collection by the original microfilm deposit created by John Crane (CPCrane Papers) and the larger and more recent additions (CFPCrane Family Papers). The manuscript memoirs of Charles Crane are of special importance, though dictated to a secretary late in life, and therefore in need of verification from other sources. There are several copies with minor variances: three in the Crane Papers at Columbia, one in the Chicago History Museum, and one at the Hoover Institution in Stanford. I have relied mainly on that in box 20 of the Crane Family Papers that includes annotations by John Crane. Without the memoirs this project would indeed have been difficult to accomplish.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.