Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

For Roger Labrie

Over and over it came down to that question

What was reality in an unreal time?

Tom Hayden, The Long Sixties: From 1960 to Barack Obama

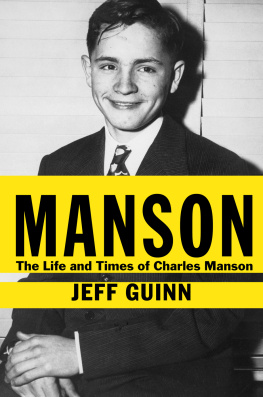

AUTHORS NOTE ON NAMES

I n almost every instance, I identify Charles Manson as Charlie because that is what everyone called him during the time that he led the Family. Most of those who knew him during that chilling era still call him that. Key Manson Family members are also referred to in this book by their first names. Otherwise, I generally observe the tradition of identifying individuals by their last names after initial reference.

It is worthy of note that as a child in McMechen, Manson was known as Charles, as he is today among many of his current friends and followers. In his letter to me, and in other letters shown to me in the process of researching this book, he signs with his full name: Charles Milles Manson.

PROLOGUE

Charlie at the Whisky

O n a summer night in 1968, three cars eased down Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. They headed for the tricked-up portion of the long, winding street known as the Strip, a 1.7-mile stretch of nightclubs, shops, and restaurants that was one of the epicenters of cutting-edge counterculture in America. Three hundred and eighty miles to the north, the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in San Francisco still clung to its reputation as the capital city of Flower Power and hippie love-ins, but its pretensions of leading the world into a new era of enlightenment through great music, free love, mind-expanding chemicals, and disdain for class-conscious, capitalist beliefs were dissolving into drug-addled violence. Sunset Strip was about music, sex, and drugs, too, but few among the amped-up throngs packing its sidewalks pretended their motivations were anything other than self-indulgent. As civil disorder swept the rest of America in response to Vietnam and racial unrest, the only major uprising on the Strip involved the closing of a popular club and the enforcement of a 10 P.M . curfew for those under eighteen. Young people flocked to the Haight in hopes of finding Utopia; youthful pilgrims came to L.A. with the dream of becoming friends with celebrities and becoming rich and famous themselves. Such dreams were encouraged by the Strips traditional egalitarianism. Stars performing in or visiting many of its famous clubs were expected to mingle with the public, chatting amiably as if with equals and, in the case of those whod made it in the record business, offering advice to the endless stream of wannabes who felt certain that their self-penned songs about love, spirituality, and revolution would make them as big as the Beatlesor even bigger.

The young men behind the wheels of the three cars inching down Sunsetsometimes it could take hours to maneuver through the traffic and crowds along the Stripwere out for a night of fun and basking in the celebrity that theyd worked so hard to attain. Terry Melcher, Gregg Jakobson, and Dennis Wilson had been close friends for years. Individually, theyd reached separate pinnacles in the music business: Melcher as a producer, Jakobson as a talent scout/recording session organizer, and Wilson as the drummer for the Beach Boys, and thus the most famous of the trio. Together they were part of an informal society known as the Golden Penetrators. Its membership was limited to anyone who had sex with women from one of show businesss most famous families. It wasnt the most exclusive of organizations; some of these women were every bit as promiscuous as the men pursuing them. The Melcher-Jakobson-Wilson triumvirate reveled in their hedonism; in a city that had long ago waived most moral or legal limits for the famous, their philosophy was Were us, there are no rules, we get to do this.

When L.A. celebrities wanted to keep their night-on-the-town discreet, they frequented clubs where steep membership fees denied entry to all but the biggest stars. But on this night Melcher, Jakobson, and Wilson were in a sociable mood. Part of the fun of being famous was being fawned over by fans, of demonstrating a certain sense of noblesse oblige, though on a controlled basis. There was considerable difference between accepting the deference of starstruck, pretty people and being pawed by packs of grubby teens. The popular public clubs on the Strip made special arrangements for visiting stars, usually in the form of restricted seating so that other customers could only stare from a distance whenever the celebrities felt like retreating from the dance floor for a while. For stars and general public alike, dancing was a big part of a night out on the Strip. While live acts were onstage, respectful attention was required. But between sets, disc jockeys played records and it was time for everyone to show off, rocking to the beat and trying to outdo each other in performing all the latest steps.

As giants of the L.A. music scene, Melcher, Jakobson, and Wilson headed for an appropriate destination on the Strip. The Whisky a Go Go, located on Sunset just past the edge of Beverly Hills, was the most famous club in town and probably in all of America. Magazines from Time to Playboy touted it as the hippest place to see and be seen. Each night, long lines routinely stretched for blocks two hours or more before the Whisky opened at 8:30. The cover charge kept out panhandlers and riffraff. Regulars always anticipated thrills beyond those to be found at any other club on the Strip. Performers recorded chart-topping live albums at the Whisky. The flower of the music scene regularly dropped in; recent visitors included Jimi Hendrix, Neil Young, and Eric Clapton. Hendrix and Young even jumped onstage to jam. The Whisky usually alternated lesser-known local bands with big-name acts like the Turtles and Eric Burdon and the Animals. The club had been one of the first venues on the modern-day Strip to feature black musicians. Among others, Buddy Guy and Sly and the Family Stone graced its stage, and when Little Richard performed, rock gods Mick Jagger and Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones came to hear him. Every visit to the Whisky was certain to be special in some way. Anyone in Los Angeles who had pretensions of being cool had to make the scene. Even Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton partied there.

The nightly crowds meant parking was scarce anywhere near the club, but that was no problem for Melcher, Jakobson, and Wilson. The operators of the Strips jam-packed lots always found room for vehicles belonging to stars. Melcher handed over the keys of a black four-door Mercedes convertible. Jakobson arrived in a black, mint condition 1939 Pontiac; hed just swapped a Porsche for the vintage ride. Wilson pulled up in a burgundy Rolls-Royce recently given to him by his older brother, Brian, the reclusive leader of the Beach Boys. As the trio strolled into the Whiskythere was no need for them to stand in line, or pay the nights cover chargeeveryones eyes were on them. Wilson, a big, handsome man, would have been recognized by virtually every music fan in the country. Melcher and Jakobson werent household names in Middle America, but the Whisky crowd, most of them savvy to all aspects of the L.A. music scene, knew who they were and why they were important.

That wasnt true of the fourth member of the party, whod arrived in Wilsons Rolls. To the onlookers outside the Whisky, there wasnt anything special about thirty-three-year-old Charlie Manson, just one among thousands of ambitious singer-songwriters whod made their way to L.A. with the goal of getting recording contracts and becoming superstars. Manson was short, about five foot four, and scrawny. For much of the summer, hed been lucky enough to mooch off the Beach Boys drummer, who was notorious for giving strays temporary run of his luxurious log cabin house further down Sunset Boulevard. Most of them drifted off after a day or two; Manson showed no sign of leaving. For a while, that was fine with his host. Besides writing some interesting songs and spouting an addictive form of philosophy about surrendering individuality, Manson had with him a retinue of girls who adored Charlie and were happy to engage in any form of sex his rock star benefactor desired. Accordingly, Wilsons summer was a carnal extravaganza, though he had to make frequent trips to his doctor since the Manson girls kept infecting him with gonorrhea. In between sex romps, Wilson good-naturedly touted Mansons music to the other Beach Boys and to friends in the L.A. music scene. To date, no one had been impressed enough by Mansons songs to offer the scruffy drifter the recording contract he craved. But Charlie had unwavering belief in his own talent and in Wilsons ability, even obligation, to make it happen.

Next page