Contents

Guide

Page List

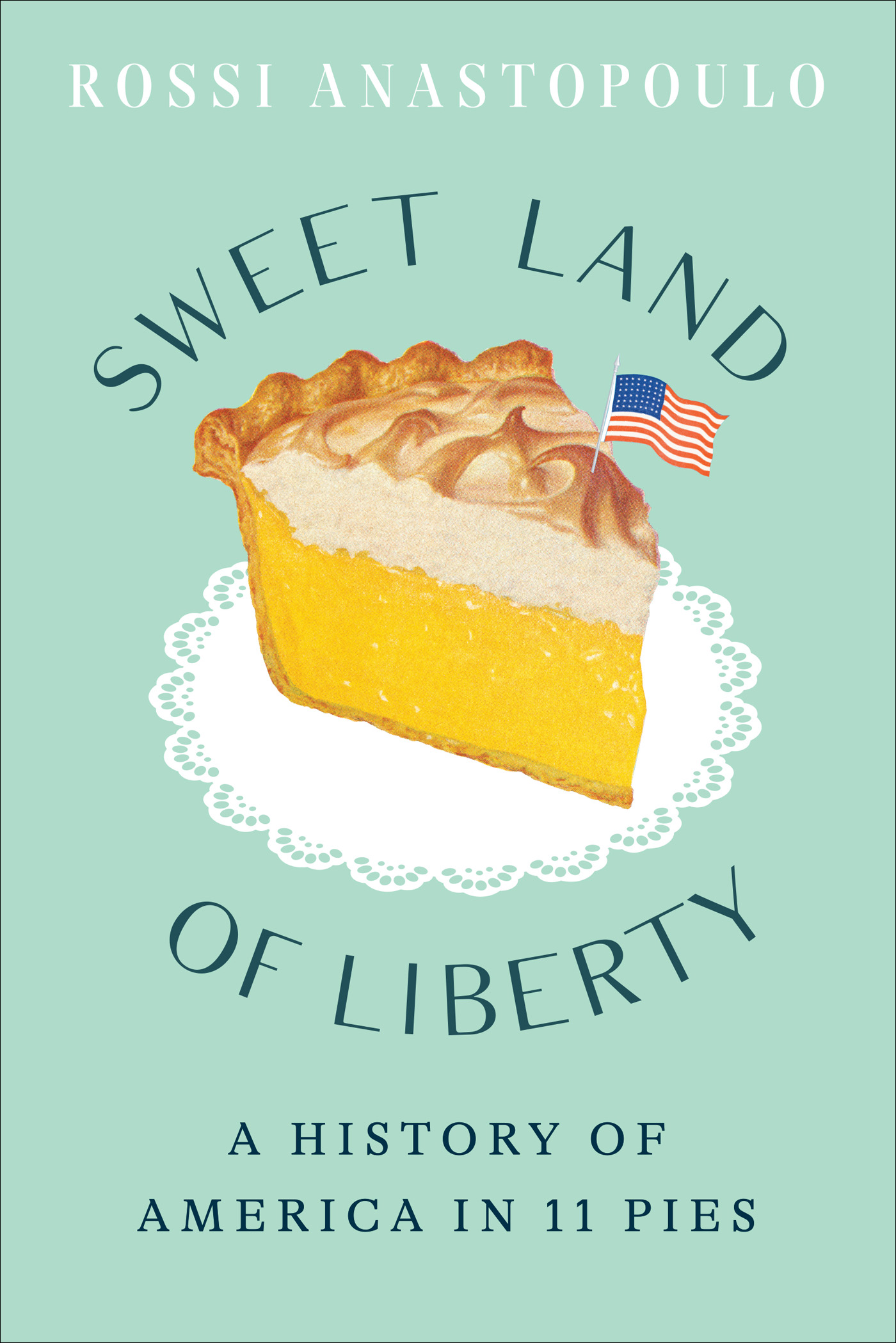

Copyright 2022 Rossi Anastopoulo

Illustrations by Jenice Kim

Cover and cover 2022 Abrams

Published in 2022 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

has been adapted from the authors article The Pie Engineer Who Designed a Dessert for the Jazz Age, first published by Atlas Obscura on March 24, 2020.

has been adapted from the authors article The Radical Pie That Fueled a Nation, first published by TASTE on November 13, 2018.

has been adapted from the authors article Why Apple Pie Isnt So American After All, first published by Food52 on October 8, 2021.

Recipe for courtesy of ACH

Recipe for reprinted with permission from Pie Any Means Necessary: The Biotic Baking Brigade Cookbook (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2004), 108.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022933714

ISBN: 978-1-4197-5487-6

eISBN: 978-1-64700-305-0

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

For my yiayias.

To my Yiayia Harriet, whose pies started this all.

And my Yiayia Rosie, who taught me to meet everything with a laugh.

LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The majority of this book was written on the ancestral homelands of the Tongva people, who were enslaved, assimilated, and forcibly removed through colonization. I honor their right to this land and pay my respects to generations past, present, and future.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

On February 1, 1960, Ezell Blair Jr. entered the F. W. Woolworths lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, along with several of his friends, took a seat at the counter, and ordered coffee and a slice of cherry pie.

Woolworths was a popular lunch destination in Greensboro, a place where you could go for a quick burger or sandwich, maybe a cup of coffee with a slice of pie on the side. The interior was basic but comfortablea row of metal-backed stools lined a long counter littered with sugar canisters and salt and pepper shakers, behind which servers in paper hats took orders and refilled coffee cups.

It was the sort of democratic spot that served a large cross-section of the towns population, from local lawyers in suits to thrifty college students from nearby UNC Greensboro.

There was one exception to this clientele, however. Woolworths did not serve Black customers.

Ezell Blair and his three friends, all of whom were Black, knew this when they entered Woolworths that winter day. As freshmen at the local North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, they were accustomed to the strict racial codes that governed Greensboro, dictating where they could eat and shop and live. Therefore, unlike all other patrons, their trip to the Woolworths lunch counter that day was meticulously planned.

Inspired by nonviolent protest, including a television program he had previously watched about Mahatma Gandhi, Blair had joined his friends in organizing a deliberate civil rights protest by staging a sit-in at the all-white Woolworths lunch counter. The tacticwhich had already been employed several times in lunch counters throughout the Southwas decided after the group dared each other to do it during a campus bull session. Determined to be organized and disciplined, the students planned their approach deliberately, plotting their route to ensure success.

First, the group stopped at a nearby store owned by white businessman Ralph Johns, a social activist who supported the NAACP and was sympathetic to their cause. Next, the four young men visited the Woolworths five-and-dime store, where they purchased several items and carefully saved their receipts. Finally, they took their seats at the Woolworths lunch counter and politely placed their orders, with Ezell Blair Jr. requesting coffee and cherry pie.

It seems no coincidence that Blair ordered pie during this historic moment. The dish was a staple of Southern diners and lunch counters, part of the distinctly American cuisine such establishments served, and it could be found in similar lunch spots across the region. Pie was a familiar order. It was also deeply and traditionally Americana direct product of the United States. It seemed that if a Black American could eat piethis symbol of American innovation and identityat a lunch counter in North Carolina or anywhere else in the South, he or she might be considered just as equal an American citizen as anyone else.

Seated calmly at the lunch counter, the four men were immediately denied service. Unfazed, they remained, refusing to be denied. Blair waited for his slice of pie.

Unlike white Woolworths patrons, he didnt receive it.

And thus, with one order, Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond sparked a wave of social protest that ignited throughout the region. The next day, more students from North Carolina A&T arrived at Woolworths to protest alongside the four men. Two days later, Black protesters were seated in sixty-three of the restaurants sixty-six seats, with employees occupying the remaining three. The protest rippled out beyond Greensboro to Charlotte, Winston-Salem, and Durham, and eventually as far away as Jackson, Mississippi.

While pie was ordered by civil rights activists in sit-ins throughout the 60s, it played a different role in these protests for white people intent on opposing the fight for desegregation. For Black customers and protestors at lunch counters, being served pie was a symbol of equality, but segregationists instead turned the dish into a weapon of division. In many instances, the white reaction to Black protesters became violent, and when this happened, they often pelted activists with food and smeared them with pie.

Ann Moody, a participant in a sit-in at a Jackson, Mississippi, Woolworths in which angry white high school students began violently attacking the protesters, recalled: We bowed our heads [to pray], and all hell broke loose. The mob started smearing us with ketchup, mustard, sugar, pies, and everything on the counter. In these instances, pie became politicized and racially charged. Now, transformed into an object used for intimidation and power, it was a weapon for those aiming to preserve the status quo.

In these lunch counter settingsbattlegrounds over which some of the fiercest wars of the Civil Rights Movement were wagedcontrol over pie became a metaphor for racial victory. For Black Americans, being served pie represented a win for equality and justice; meanwhile, white Americans sought to reclaim the dish by using it as a tool in physical assaults. Underlying this struggle is the fact thatlike much of the food prepared at these Southern lunch countersthe pie being served was a descendant of both Black and white culinary influences.