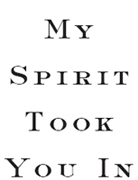

Copyright 2015 by Louise Troh

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without the written permission of the Publisher. For information address Weinstein Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this book.

Editorial production by Marrathon Production Services.

www.marrathon.net

BOOK DESIGN BY JANE RAESE

Set in 12-point New Baskerville

ISBN 978-1-60286-290-6 (e-book)

Published by Weinstein Books

A member of the Perseus Books Group

www.weinsteinbooks.com

Weinstein Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

FIRST EDITION

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO AMERICA, AFRICA, AND THE WORLD

CONTENTS

I stayed in a chair as Eric Duncan crossed my living room in Dallas, Texas. It was about 10:00 p.m. on September 20, 2014. I had not seen him in sixteen years.

He was over six feet tall, with a shaved head. I am not such a big woman, five feet and four inches. I stood up and greeted him. You are so big.

This was not such a good thing to say for my first sentence, but it was all I thought of. He was so skinny when we met twenty years ago. At that time, Thomas Eric Duncan, known to everyone as Eric, was barely a man. Exiles on the run from the war in our country, Liberia, we lived with thousands of others in a refugee encampment in Danan, a city in the Ivory Coast. Then Eric was a kind almost-man growing into a gentle grown man.

Eric was one of many people I loved in my life, but always I loved him special. I cant say why; it was like God picked us for each other. Our spirits knew each other from that first day when he called out to me on a dusty road in Danan.

In my living room Eric said, I thought you would be bigger, eating all this American food.

You cant eat everything here or you will be too big, I told him.

We were nervous.

Erics face was broader now. He was older but the same. He had some gray in his beard, but when I looked at him I could see both men: the young one from the Ivory Coast and this older one, tired from his travels, who had wanted us to be together for so long.

When Eric came to Dallas I was afraid he would not love me when he saw how old Id become. I was fifty-four years old, ten years more than him. My legs hurt. Gray was coming into my hair. I worked as a certified nurse assistant at a senior living center. My hands were rough from so much Clorox, so many years of cleaning. Dishes. Pots. Sinks. Diapers. Toilets. Floors. Cleaning everything. And the next day, cleaning again.

Over the years I told Eric many times that I was too old for him; but he said no, never. And I had laughed, the soft African laugh that has only a little sound and means all is well. It means we are together in this thinking, but I am waiting to see what will happen. Laughing sometimes tells more than words.

I told him that I needed to protect my heart. It was old and tired, and I could not risk it again.

On the phone he said, I will not hurt you. I will make you happy. Let me try.

Afraid to hope, I said nothing.

Since the days wed met in the Ivory Coast he had loved me. Always he said, You are my wife. It doesnt matter where you are. You are the mother of my son, the love of my life.

In the Ivory Coast I was a woman who had to be tough, because I was a mother with children to feed. I was skinny then, legs like sticks, dried-out skin, refugee-ugly. I could not be gentle with the world. A mother must be a tiger so that her children can survive. A mother who has nothing to give her children must give them her whole spirit. She must never let anything scare her so much that she will not defend those she loves.

I learned these things from war and exile, and then from living in America, where life is good but not as easy as Liberians think it is. When I came to America in 1998 as a political refugee, I left Eric, our son, Karsiah, and all eight of my other children in Africa. Nine children, Americans say with wide eyes; they cant believe it. I had ten in all; now nine are living.

There was no birth control in Africa. In high school, Id been the smart girl, so mean to other girls when they were pregnant. I would say they should stay home and be pregnant, forget school. I wouldnt even sit with them. But young women fall in love and sometimes not with the right men. Before high school was over, I was pregnant myself. I could not continue with classes. I stopped going to school. But my father welcomed me in his home. He protected me and my baby.

In war, many fathers die or disappear. Some of my childrens fathers had gone that way. Eric was still with me, a refugee in the Ivory Coast, when word came in 1998 that I could come to America. But I could not take him or my children with me. The visa was for one person only, not for a family. Alone is the only way. We leave our husbands and our wives, we leave our children, because only by leaving can we give them any hope for a better life.

Many years I worked to bring my children from Africa to America. Id brought the youngest, Erics son, Karsiah, in 2006 when he was ten. In 2005 and 2006, Id brought four of Karsiahs older sisters. Only one sister, Kebeh Jallah, was left in Liberia. But she died before the visa came. No visa: such hopeless words. Three sons remained behind. I hoped I would see them again someday. My tenth child, Timothy, was born in America.

The big dreams of Erics life were coming to America and being with me. In all the years apart, neither of us ever matched that love from long ago with anyone else. It would not die. I gave up on ever having him in my life, but he never gave up on us.

Sometimes over the years Erics mother called to say that I must send her son money. She is in North Carolina now. Why did she not call her other children? Always, it seems she called me. From the first time so many years ago when she saw me dancing down the street with other peopleall of us dancing and playing music, going house to house the way Africans do sometimesnot being such a good dancer, just having fun, she saw my heart. Her son did, too. He knew my self.

When relatives and friends call me from Liberia pouring desperate words into my ears, I send them what they ask for. Sometimes it was Erics mother who called and sometimes it was Eric himself calling me, pleading. Maybe he was ashamed, but he was needing that money so much that he could not be prideful. He had other girlfriends whod made it to America. Some of them would have their husband answer the phone or they would not answer at all. Maybe theyd say yes, but then not send the money.

Next page