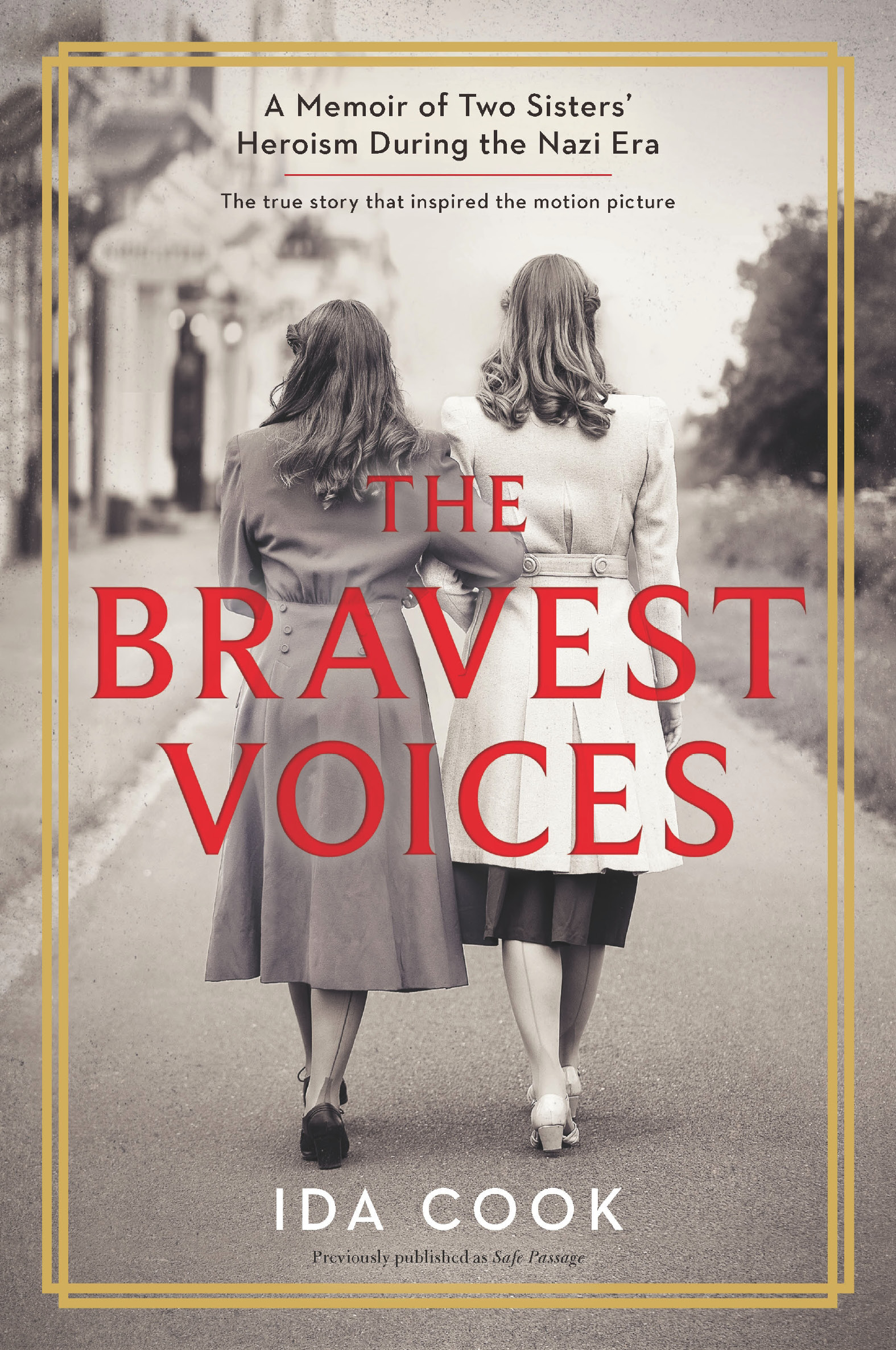

Praise for The Bravest Voices

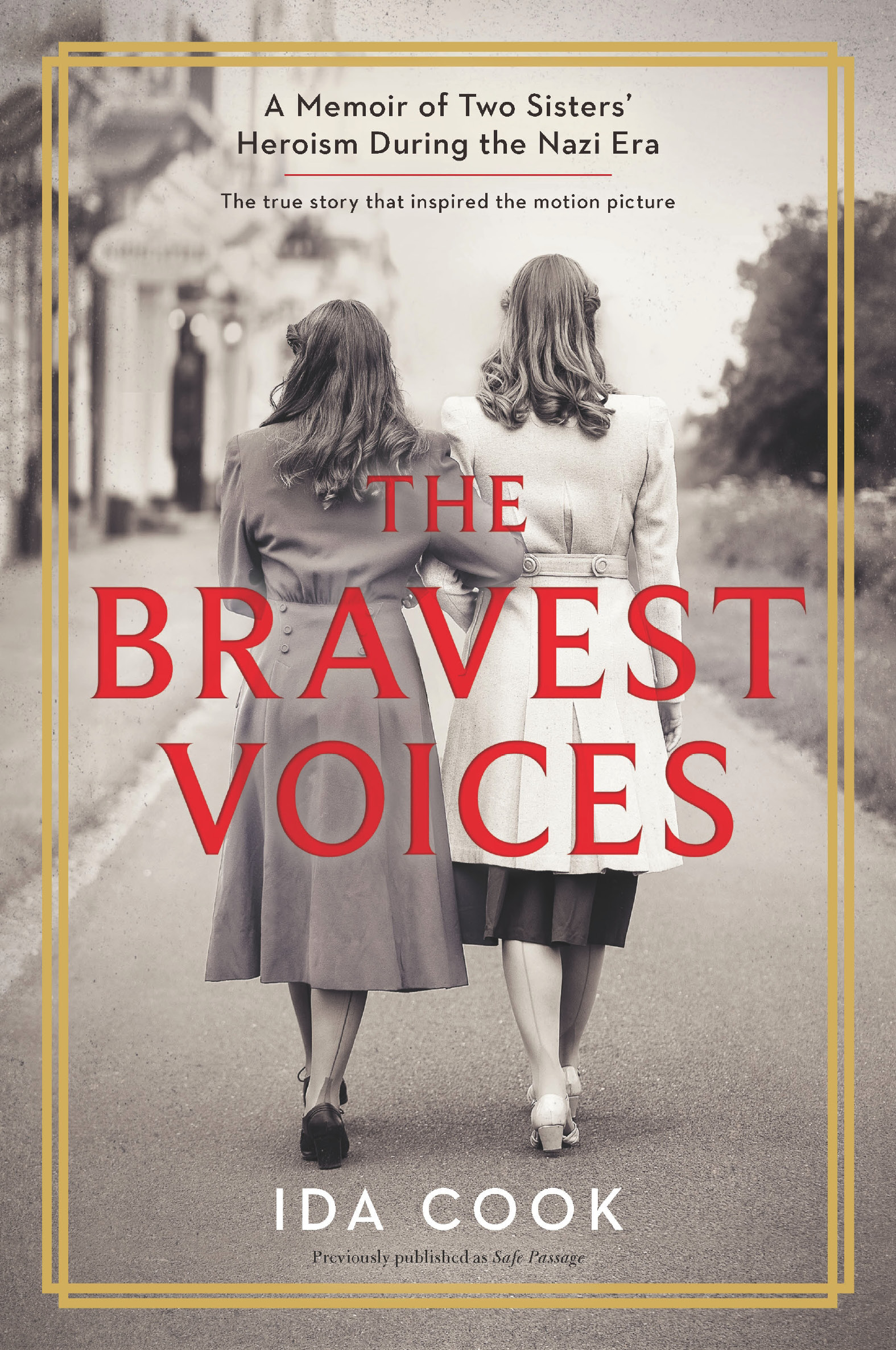

An enchanting memoir... [A] charming, harrowing tale of the Cook sisters, Ida and Louise, whose holiday from their suburban London home to the United States and Western Europe turns from a music lovers grand tour into an international mission to save Jews from the Nazis... Pocked with heart-stopping momentsclose calls and reunited families rank highthis lovingly written true story shines a light through one of humanitys darkest chapters.

Publishers Weekly , starred review

The extraordinary story of two British sisters who became unlikely heroines in helping Jews to flee Nazi persecution.

The Guardian

A breathtaking story.

Daily Mail

The Cook sisters defy the generalisation of social history: they were extraordinary.

The Telegraph

To the outside world, Mary Burchell was a prolific Mills & Boon author who entranced her fans with tales of intrigue, passion and danger. But in private, Burchellknown to her family as Ida Cookhad lived an equally daring life, undertaking risky missions alongside her sister Louise to help rescue Jewish families trapped in pre-war Austria and Germany... Their incredible story is retold in Cooks memoirs.

Jewish News

A unique story, simply told.

Kirkus Reviews

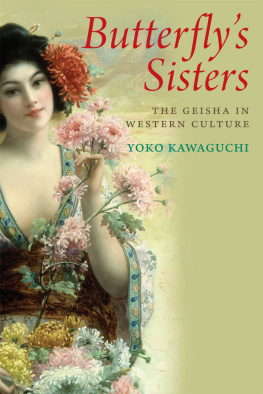

THE BRAVEST VOICES

A Memoir of Two Sisters

Heroism During the Nazi Era

IDA COOK

Ida Cook (19041986) authored more than one hundred and twenty books over the course of five decades. A lifelong devotee of opera, she counted Amelita Galli-Curci, Rosa Ponselle and Maria Callas among her close friends. In 1965, Ida and Louise were awarded the honor of Righteous Among Nations from the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial Authority. The sisters were also posthumously awarded the British Hero of the Holocaust from the British government in 2010.

To my incomparable parents, without whose loving and commonsense upbringing we should never have been capable of doing the things described in this book.

Contents

DISCLAIMER

Ida Cooks memoir The Bravest Voices was originally published in 1950 under the title We Followed Our Stars. The publisher has preserved the original language of the author to accurately represent those times and modes of expression, and to stay true to her story. In addition to being a work of autobiographical nonfiction, it is also a primary source for an account of the Holocaust, and thus the memoir has been kept as it was written for the sake of historical record.

FOREWORD

Romance is not just about love. Its about an attitude to life, and there is little more romantic than a profound faith in the possibility of all things.

It could be a belief that when you kiss the ugly toad he will turn into a handsome prince just as much as a conviction that if you do the right thing you can, against all the odds, save a life. What could be more romantic than helping people, strangers, otherwise condemned to likely death, escape their own country and survive in a new one? For Ida and Louise Cook the spirit of hope, the conviction that everything would come all right in the end, was the essence of life. It pervades the romantic novels written by Ida, but it also guided the daily existence of both sisters. No matter what evils they encountered in the world, what remained constant for them was hope.

When I first discovered this remarkable book it was the unshakable faith of Ida and Louise Cook that they could make a difference that hooked me immediately. It was the artless innocence of two young women flying to another countryat a time when flying itself was dangerously newdefying that countrys laws to help desperate people they did not know, that made such a profound impression. I was moved by the sisters certainty, so rare today in a world where moral equivalence holds sway, that they knew without any ambiguity a clear difference between right and wrong.

Ida and Louise Cook were born at the beginning of the last century; Louise, quieter and more intellectual in Dorking, Surrey, in 1901; Ida, naturally garrulous, three years later in 1904 in Sunderland, Northeast England, where their father, a Customs and Excise officer, was posted. Both came to maturity during the harrowing years of World War One, a war that wiped out almost a generation of young men in England. Two ordinary women who lived in extraordinary times.

In the pages that follow there are innumerable examples of their pluck, to use an almost forgotten contemporary word. How Louise would leave her drab civil service office on a Friday evening, dash to Croydon airport for the last plane to Cologne, then the night train to Munich, where they would, with luck (Ida often credits things going right to good luck, too modest to recognize it is hard work instead) arrive for breakfast on Saturday morning. Minor inconveniences such as toothache and overdrafts were ignored. They spent so much of their own money on these rescue missions that Ida admits toward the end of the book that she was in significant debt.

Money was never one of their gods. They made their own clothes, traveled third class and, even when Idaknown as Mary Burchellbecame one of Mills & Boons bestselling authors earning almost 1,000 a year from her novels, they still sat in the gallery rather than the stalls of their beloved Covent Garden. We spent thousands in our imagination, she wrote when her advance for two books was a mere thirty pounds. By the time she was earning thousands, she had other ideas.

The problem they were confronting was that the British government, since the Nazi seizure of power in 1933 when Jews had been gradually stripped of all rights, had allowed very few Jewish refugees to flee to Britain, and then only if financial guarantees for their future stability were in place. The situation deteriorated dramatically in November 1938, following the outburst of violence at Kristallnacht when thousands of Jewish homes and businesses were destroyed and looted. This night of carnage shocked many British people who until then had ignored the plight of the Jews in Germany and Austria. The British government now agreed to ease immigration restrictions for Jewish children, but were still not prepared to allow unlimited entry for adults, many of whom found it impossible to leave. In this crisis private citizens or organizations had to come up with guarantees to pay for each childs care and education or to provide for an adult, which for a woman, usually meant domestic service. Adult men were accepted only if they had documentary proof that they were in transit and therefore faced the direst problems.

Ida and Louise, partly in order to make financial guarantees easier and because they recognized that those they were rescuing hated the idea of living off charity, offered to smuggle out valuablesmostly jewelry and furs. The refugees could sell these and have something to live on once they arrived in England. But in late 1930s Nazi Germany, smuggling currency or valuables was a serious crime. By helping opponents of the regime, as they did on at least one occasion, they risked their own lives. Yet the only precaution they took was varying their return journeyperhaps coming home through Holland, catching the night boat and arriving at Harwich early on Monday morning so that Louise could walk into her office just in time. Their only weapon was faith in their British passports.

Ida describes their journeys straightforwardly, not enhancing her or her sisters role with the narrative storytellers skills at her disposal. There is no need for added drama. It soon became, she says, a regular and serious pattern of work. Yet who can forget the image of the nervous and eccentric opera-loving sisters, an image they themselves encouraged as a cover story, wearing cheap and cheerful clothes, embellished with fine pearls, expensive wristwatches and other jewels. Once, Idas jumper was adorned with a particularly huge oblong of blazing diamondssomeones entire capitalwhich she had to pass off as fake paste from Woolworths.

Next page