Contents

Guide

Page List

Copyright 2021 Peter Hoffman

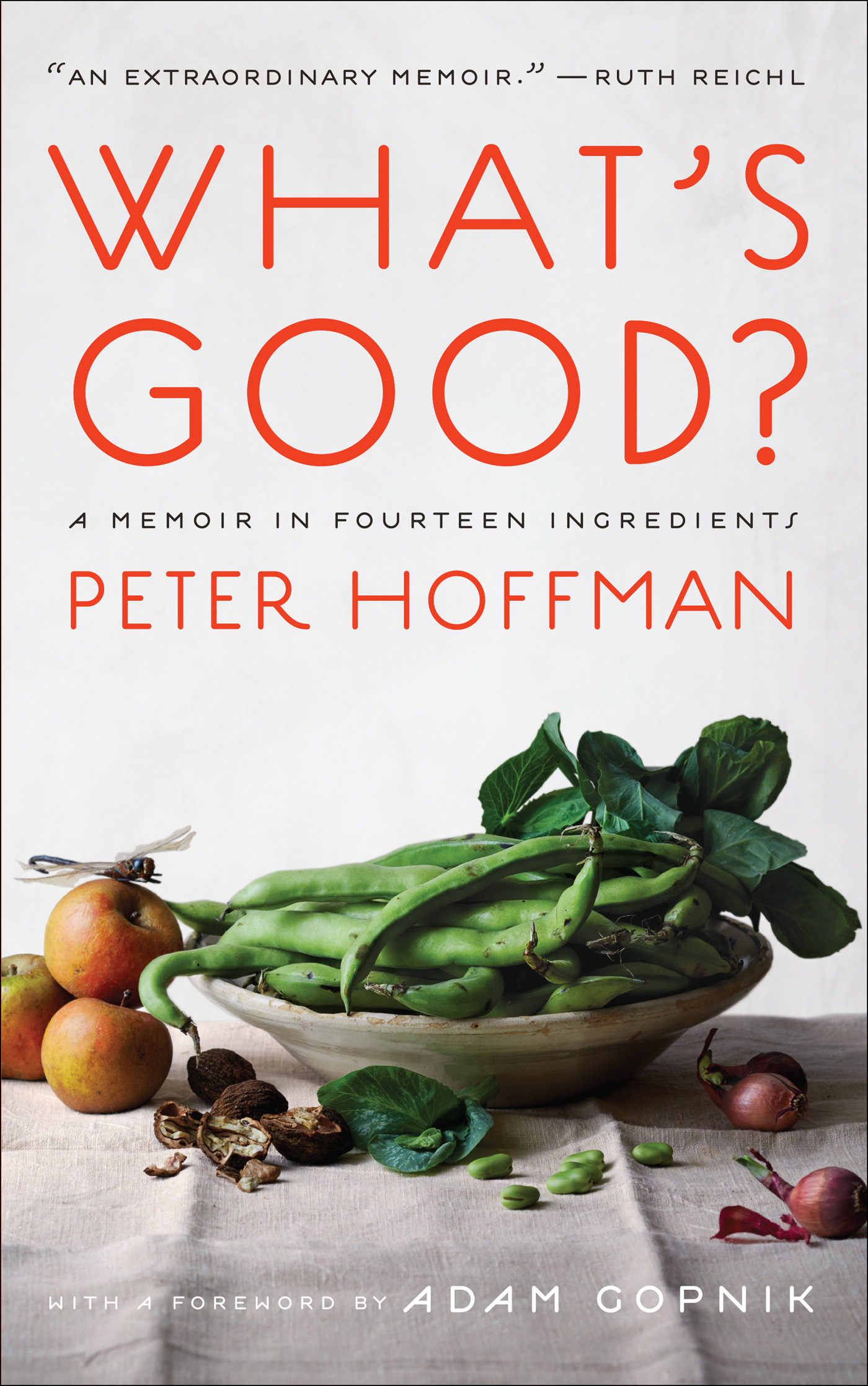

Cover 2021 Abrams

Published in 2021 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020944979

ISBN: 978-1-4197-4762-5

eISBN: 978-1-64700-009-7

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

To Susan, my wise partner and devoted champion.

To Olivia and Theo, who learned alongside me much of whats described here and carry it forward as avid cooks and global citizens.

CONTENTS

RECIPES

First-rate raw materials are the very foundation of good cooking. Give the greatest cook in the world second rate materials and the best he can produce from them is second rate food.

Paul Bocuse

Eating with the fullest pleasurepleasure, that is, that does not depend on ignoranceis perhaps the profoundest enactment of our connection with the world. In this pleasure we experience and celebrate our dependence and gratitude, for we are living from the mystery, from creatures we did not make and powers we cannot comprehend.

Wendell Berry

A FOREWORD

ADAM GOPNIK

Some friendships start, like the universe itself, in high heat and gradually cool down; others are more like the movement of the tectonic plates, proceeding in long, slow passage through the years until they bump into one another for good and merge to form a continent. My friendship with the author of this book is of the second kind. We began as client and chef, became collaborators and colleagues, and have ended, I think, as the best of friendsso much so that I take partial, guilty responsibility for the inspired title he has given this book, as one among many in the annoying chorus of greedy people who, visiting the New York City greenmarket at Union Square with him, or merely bumping into him there, demand urgently: Peter! Whats good?

As we ask, were confident that, whether talking ramps or beans or shrimp or pea pods, spring strawberries or summer peaches or winter potatoes, Peter Hoffman knows whats good and will quietly point you to the one right stand to get it. (Or even actually accompany you there, where his friendship with the farmer selling the good goods makes for a ten-minute catch-up before the normal business of buying and selling commences.) Peters intimate relation to the greenmarket and its farmers is, ironically, one of the purest forms of urbanism I know: it is the place where weak ties, the bumping-into relationships that broaden the spectrum of intimacy in cities, still lives, even at the height of a pandemic.

But this book, in addition to being as good a market guide as one could hope to find, with wisdom applicable to farmers markets far outside New York, is something more: the story of an artist who is also an artisan. I keenly recall seeing Peter for the first time in the early 1990s, in his magical SoHo restaurant Savoy. What made Savoy unique among the first-rate restaurants of New York was its presciently handmade quality, and its insistence on practicing the craft of cooking within the happy, normal range of experience. It was not a place to go for ten courses and a long lecture with each oneit was just where you went, planned or, sometimes, on impulse, for a perfect dinner.

Perfect is a scary word to use, but Savoys perfection was achieved in part by imperfection, by the place not trying too hard. Perfectly lit by a copper mesh light above, perfectly served by an attentive but not servile staff, with his wise wife, Susan Rosenfeld, often in attendanceand early on working there as still the best pie-maker of my experiencemy wife and I watched as the host and owner and chef moved among tables, a guy my age whose care and attention were divided among the entire house.

But I sensed too what I did not yet knowthat the appealing young man was also an artist in the grip of a peculiar passion that, like all artists passions, proposed previously impossible reconciliations: to make a new kind of eclectic, Mediterraneaninspired, yet wholly American cooking; to scrub away the last encumbering barnacles of the old slavishness to French cooking without neglecting the glory of France (I knew from our first tableside conversations that he, like me, was an admirer of the arch Francophile writer Richard Olney); above all, to make a place for a weekday dinner that was also a place where minds could meet and make values, to cook from an American palette without being tiresomely local. I was engaged at the same time, in my own writing about food and the philosophy of eating, in what I imagined to be a similar obsession, wanting to bring the brio and tone of the New Yorker writers on appetite I loved, A. J. Liebling above all, safely into the end of the century. We were sharing a new time, when we drank less, cared for our children more, cooked home as much as we ate out, and, generally, with significant exceptions, ate less for spectacle and show and more for company and conversation.

I left for five years in Paris with that ambition in mind and had our farewell meal there... I still have pictures taken that night. Coming home in 2000, Peter and I discovered, in the way of generations, that our paths had coincided even more: we came home from Paris with a baby girl named Oliviaa name we had thought uniquely original and Shakespeareanand found Peter and Susan with... a baby girl named Olivia. (Everyone had a baby girl named Olivia in the late nineties.)

Peter and I grew closer as I entered ever more deeply into the world of food, and we began to collaborate on talking dinners, some of them unforgettable, not least celebrations of the great French trilogy of bouillabaisse, cassoulet, and choucroute. They remain highlights of my own life as a speakerseminars in gastronomic history that were underlit by actual gastronomytalking about food while eating it.

Yet one need never have eaten at Savoy, or even seen it in passing, to relish this narrative. What Peter offers the world in this memoir is, really, the history of the passion that was incarnated in that restaurant. Even if that restaurant, like too many good New York things, became the victim of real estate madness and neighborhoods altered, the passion still lives, and even rages. In this beautiful, bittersweet, confessional, yet still appetite-fueled reminiscence he has written about many objectsthat memoir of the rise and fall of a neighborhood and a restaurant, a testament to a particular vision of food, and a useful guide to what is good in any greenmarket and how we might go about discovering that for ourselves; his real subject is the life of a chef, or cook, as an artist. For cooks, he reminds us, are as much artists as any other kind, yet work with material and circumstances more resistant than any other kind of artist knows.