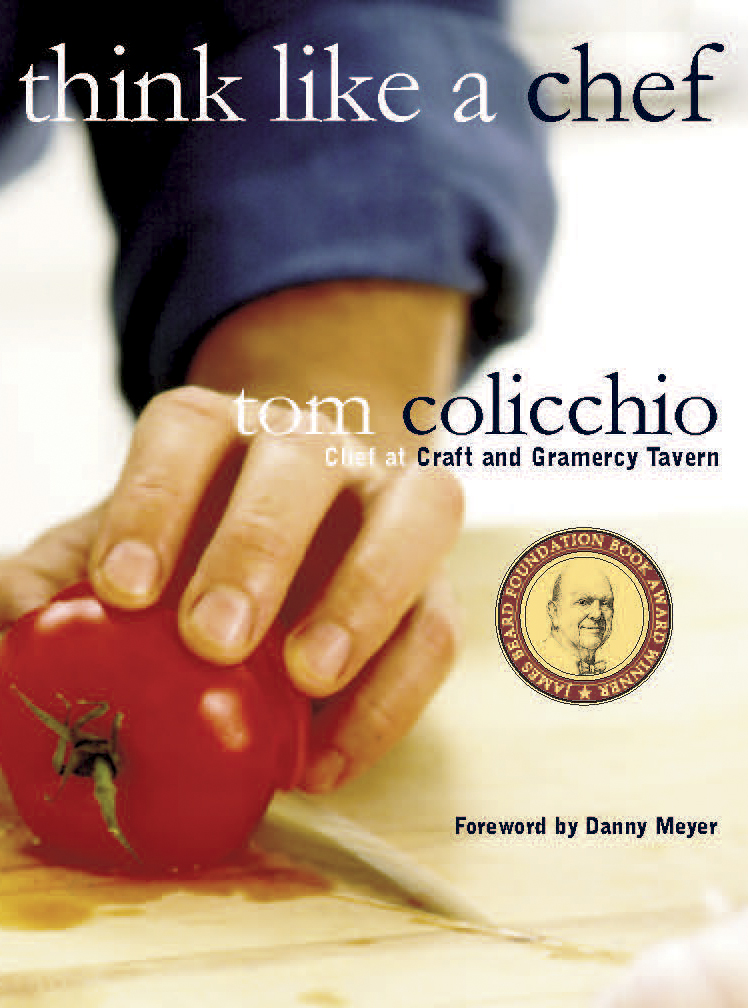

Copyright 2000 by Tom Colicchio

Photographs copyright 2000 by Bill Bettencourt

Foreword copyright 2000 by Danny Meyer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, New York, New York

Member of the Crown Publishing Group.

Random House, Inc. New York, Toronto, London, Sydney, Auckland www.randomhouse.com

CLARKSON N. POTTER is a trademark and Potter and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Colicchio, Tom.

Think like a chef / Tom Colicchio with Cathy Young, Lori Silverbush and Sean Fri; photographs by Bill Bettencourt.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Cookery. I. Young, Cathy. II. Silverbush, Lori. III. Title.

TX651.C64 2000

641.5dc21 00-022983

eISBN: 978-0-7704-3389-5

v3.1

To the memory of my father, Thomas,

and

for my mother, Beverly

contents

foreword by danny meyer

I first encountered Tom Colicchios food in 1991, not at his restaurant, Mondrian, but at Share Our Strengths Taste of the Nationthe New York restaurant communitys annual charity event to fight hunger. Thirty-six of the citys very best chefs had volunteered to prepare seven hundred tasting portions apiece of their signature dish for a discriminating crowd of foodies. As the events organizer that year, I learned a lot about the three-dozen chef participants. Its a challenging, hectic night for a chef and the style with which they each approached the evening spoke volumes about them not just as cooks, but also as professionals and human beings. Many were nervous or disorganized, some chose to prepare very simple dishes they knew would be crowd pleasers, and a handful seemed to view the event as a monumental pain in the neck. Then there were the chefs like Tomwho wholeheartedly embraced the anti-hunger mission, and who calmly viewed the event as an opportunity to display his culinary prowess to a group of appreciative gourmets.

Taste of the Nation was a sell-out that evening, keeping me too busy to sample food at many of the chefs tasting tables. But sensing that Id be well rewarded, I did make a beeline for Tom Colicchios table. There I saw a smiling, confident chef plating and serving something that looked odd, yet compelling. Into spiny sea urchin shells he was spooning a fondue of sea urchin, crabmeat, and pureed potatoes, and then sprinkling the rim of each tasting plate with an aromatic curry powder. A few of the less-adventurous guests moved politely along to the next table when they saw what it was. Many others, however, clamored for more. I was salivating. Tom spotted me toward the back of the line and slipped me an urchin when no one was looking.

I can remember the magic perfection of that dish to this day.

Just as it is with winemakers and the wine they produce, you can gauge a lot about the personality of a chef by the style of his foodand vice versa. Watching Tom work that night, and tasting just that one dish, I learned a tremendous amount about him as a chef. Tom is a unique man with a refreshingly personal style of cooking. He cooks like who he is. Toms food is intelligent and clean; any ingredient on the plate belongs thereperiod. His dishes have both a tasteful elegance and an un-fussy and uncontrived appearance. His flavor combinations are highly seasonal, of-the-moment ideas that are more instinctive and personal than premeditated and overly intellectualized. He is generous in cooking for your pleasure, not just for his sense of ego. His food is provocative, but it provokes you to think, Oh yeah, that makes sense. A more recent dish of Toms reminded me of my first taste of that sea urchin dish: Who else could get you to eat Braised Beef Cheeks with Poached Foie Gras and Marrow? You may have never imagined that combination, but knowing Tom, you are confident that he will pull it off, and so you order it and are profoundly happy that you did.

Nearly a decade has passed since I first tasted Toms food, and were it not for this book, Id still be wondering how it was conceived. Tom has never been one to talk about why he cooks what he does, and until now the best (and only) way to get inside his chefs mind has been to sit down and eat his food. In Think Like a Chef, Tom has opened the door to his culinary process and explainedin straight termshow his very personal style is actually based on a simple logic that can be employed successfully by anyone who simply loves great food.

Danny Meyer

New York City

preface

I never intended to write a cookbook. Ive had numerous requests over the years, but I never wanted to, mostly because for me recipes have never been the point. Frankly, I learned to cook in order to get away from recipes. I couldnt fathom how to capture on the page what inspires me about cookingthe immediacy, the creative process, the integrity of good food. I was often asked to teach classes, and a similar challenge arose there: I couldnt get interested in the mere demonstration of an appetizer, entre, and dessert, and I was convinced that my students wanted more than that, anyway, based on the questions they asked. Questions like, Where do you get your ideas? and How do you know what goes together? Instead I hit on the idea of showing how a basic ingredientroast tomatoes, say, or braised artichokescan start the chain of creative thought in motion. The class was a hit, and Ive been asked to repeat it time and again. Slowly, it got me thinking how to channel the ideahow a chef thinks about foodinto a book. The result is in your hand. But in order to fully grasp the concepts I lay out in this book, it might be helpful to understand how I got here in the first place.

My first job, when I was ten, was at the open-air food market in the Italian neighborhood of Elizabeth, New Jersey, where my Uncle George sold vegetables. This was in the days before greenmarkets came into vogue, and we were selling pretty mundane stuff: potatoes and cauliflower, I think. I watched Italian immigrants of my grandparents generation hovering over each purchase, touching the food, smelling it, picking the perfect chicken to be killed and plucked out back. Each choice was of monumental importance, and it was here that I first became aware of the significance of food in peoples lives. These old-timers would never dream of going to a supermarket to buy a plucked, wrapped chicken (no telling what you were getting), and they, in turn, influenced my parents generation. When I was growing up, we went to Dicosmos for fresh ricotta and Parmesan, Centannis pork store for meat (it sold everything, but we called it the pork store), Saracinos for bread. These things were too important to trust to the A&P.

Food, in my house, provided structure to the whole day. On Sundays we would begin, right after ten-oclock Mass, with a huge egg breakfast. I was one of three growing boys, and we went through a lot of eggs. A few hours later, maybe three or four oclock, Sunday dinner would begin. There would be cousins, uncles, aunts all over the place. Wed start off with pasta, then meats, salad, and desserts. To a kid, it seemed as though the grown-ups spent the whole day around the table. Just when youd think they were done, everyone was hungry again and would start in on the leftovers.