ALSO BY JOSEPH SASSOON

Anatomy of Authoritarianism in the Arab Republics

Saddam Husseins Bath Party: Inside an Authoritarian Regime

The Iraqi Refugees: The New Crisis in the Middle East

Economic Policy in Iraq, 19321950

Copyright 2022 by Joseph Sassoon

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in hardcover, in slightly different form, in Great Britain by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books Ltd., a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2022.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Sassoon, Joseph, author.

Title: The Sassoons: the great global merchants and the making of an empire / Joseph Sassoon.

Description: New York: Pantheon Books, 2022. Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021059644 (print) | LCCN 2021059645 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593316597 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593316603 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Sassoon, David, 17921864Family. Sassoon family. Great BritainSocial life and customs20th century. Jewish familiesGreat Britain. Jewish businesspeopleEnglandLondonBiography. Jewish businesspeopleChinaShanghaiBiography. Jewish businesspeopleIndiaMumbaiBiography. Opium tradeIndiaHistory19th century. David Sassoon & Co.History. JewsIraqBaghdadBiography.

Classification: LCC CS439 .S22 2022 (print) | LCC CS439 (ebook) | DDC 929.20941dc23/eng/20211207

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021059644

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021059645

Ebook ISBN9780593316603

www.pantheonbooks.com

Cover images: (ship) by Jacques Callot. Artokoloro / Alamy; (opium poppy) Chronicle / Alamy; (Bombay) by William Daniell, 1836. Historic Illustrations / Alamy

Cover design by Madeline Partner

ep_prh_6.0_141619437_c0_r0

For Aya

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON NAMES AND CURRENCIES

NAMES

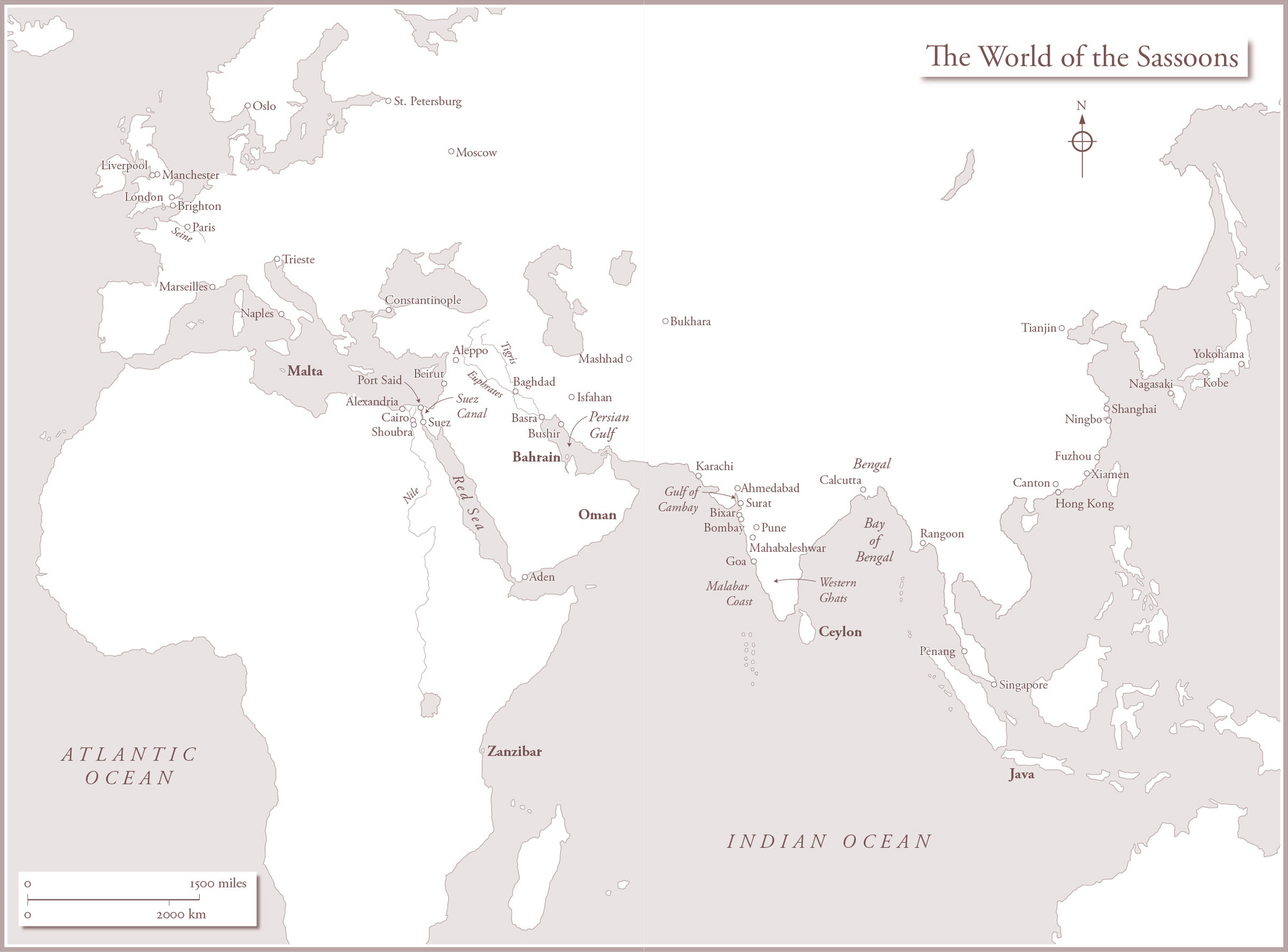

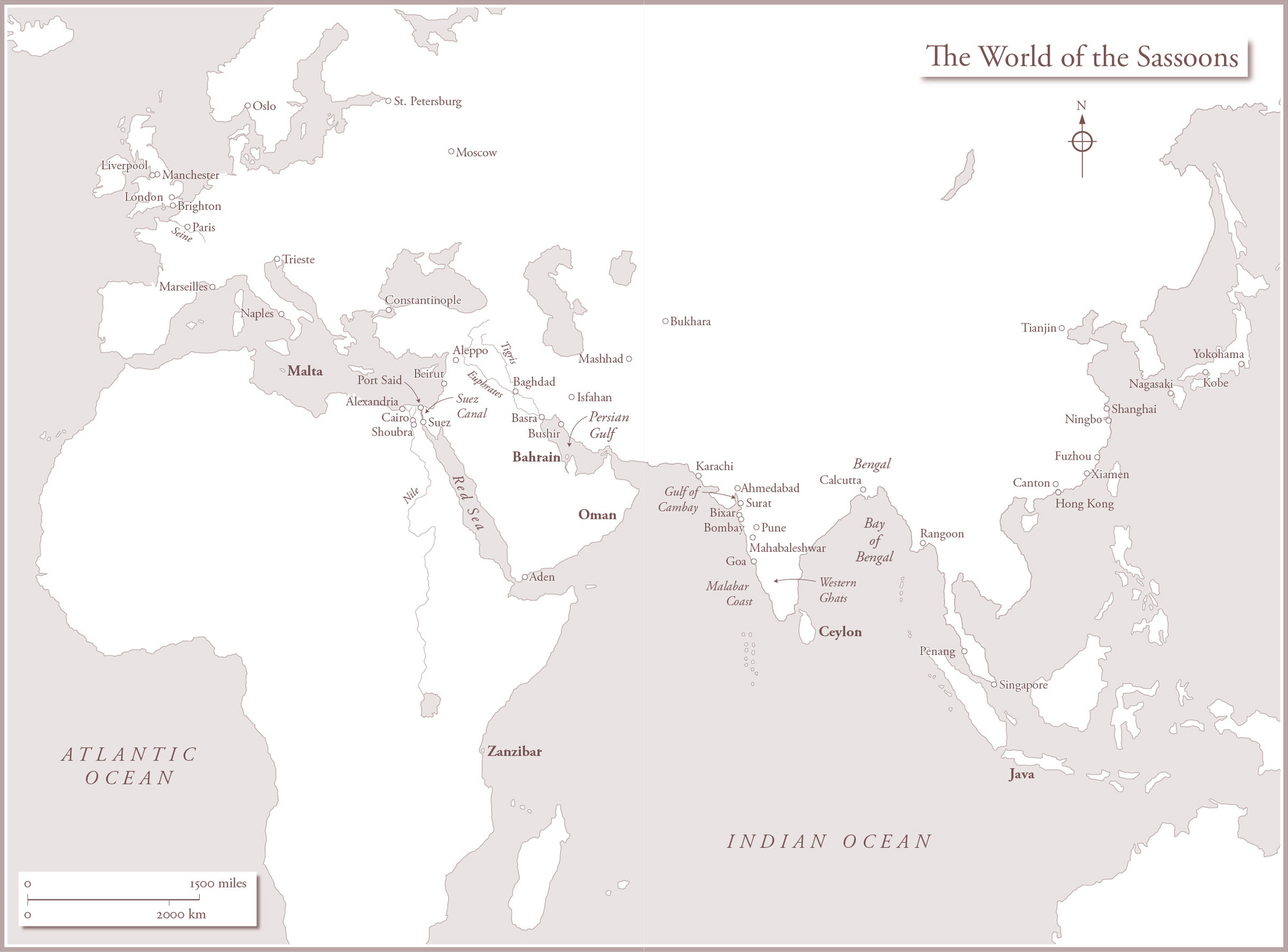

Cities and countries in this book are referred to by the name used in the historical context, so Bombay rather than Mumbai, Ceylon rather than Sri Lanka, etc. Similarly, names in China are what the family used in its correspondence.

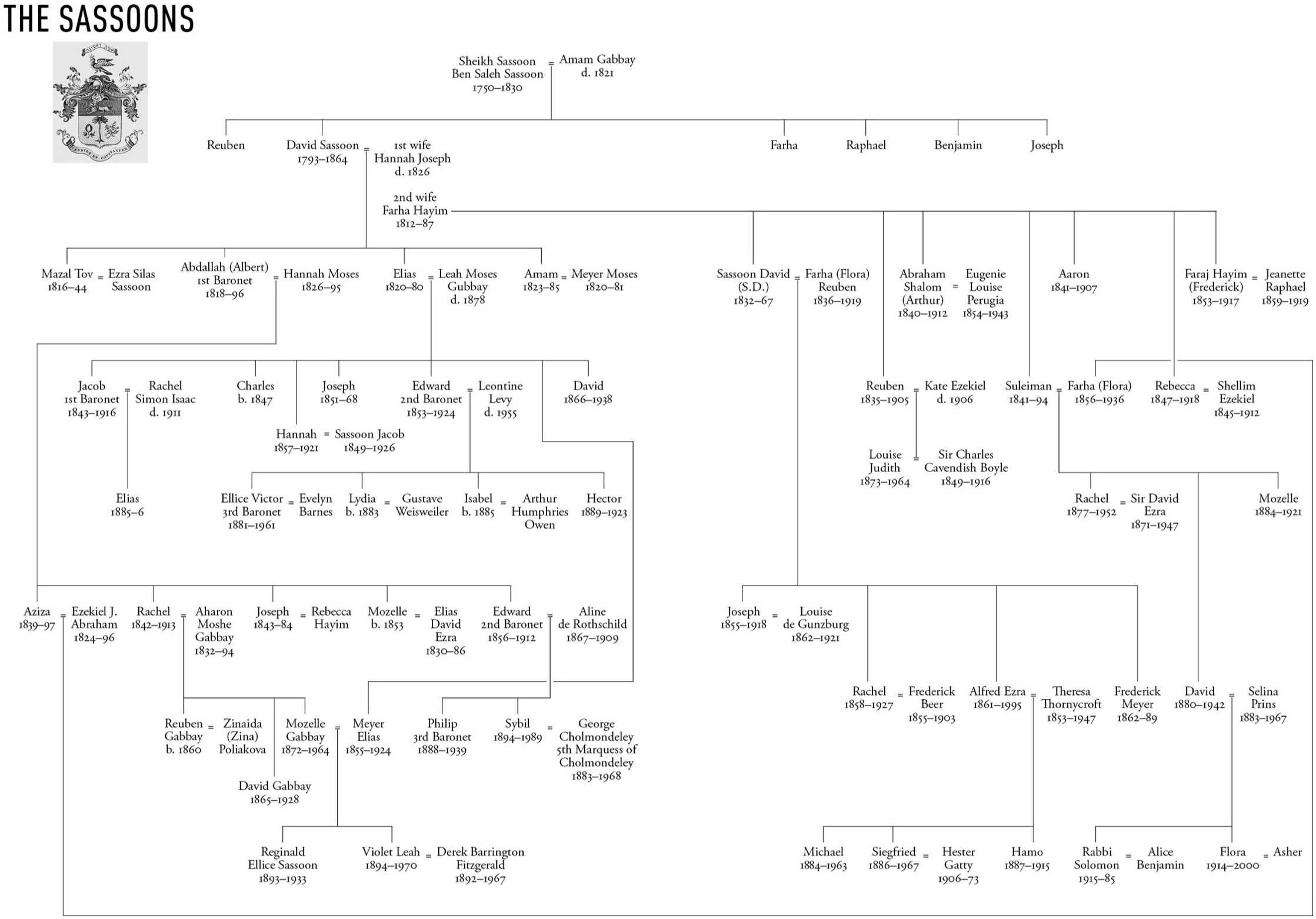

With regard to members of the Sassoon family, one point is worth mentioning: Most Anglicized their names, and so Abdallah became Albert and Farha became Flora. Arabic names are used in the book until officially changed, so it is Abdallah until he settled in London, when he adopted the English name Albert.

Some family members used the term ha-tsa-ir (the young) to distinguish them from older members who were still alive. Thus Sassoon David Sassoon sometimes signed his letters as the young Sassoon in order not to be confused with his father, who was still alive.

CURRENCIES

Obviously the pound sterling and the U.S. dollar have undergone dramatic changes since the nineteenth century, and both are worth considerably less than they were 150 years ago due to inflation. The website Measuring Worth (www.MeasuringWorth.com) was used to bring a sense of values today, although this is far from being accurate as there are multiple ways to measure the value of currencies.

As most of the story takes place in India, the Indian currency, the rupee, is mentioned regularly. The appendix compares the value of the rupee in pounds sterling and U.S. dollars from 1850 to 1910.

PREFACE

It all began with a letter. Returning to my office from lunch one day during a fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford, in early 2012, I was greeted by a handwritten letter addressed to me on my desk, where it had been deposited by the college porter. The return address on the back of the envelope identified the sender as one Joseph Sassoon of Kirkcudbright, Scotland. I had never heard of the town and assumed it was a joke or a mistake of some kind. When I finally opened the letter, however, I found that its author was as described. My namesake had read an article of mine about authoritarian regimes in Le Monde diplomatique. He thought it interesting enough, but what prompted him to write was our shared surname. He declared himself a descendant of Sheikh Sassoon ben Saleh Sassoon and believed I might be also, and therefore hoped to hear from me.

I had never been much interested in the history of the Sassoon family. As a child in Baghdad, I had ignored my father whenever he attempted to educate me about my illustrious forebears, going so far as to literally close my ears to annoy him. Later, when I had embarked on this project, there were many occasions when I wanted nothing more than to hear his tales and ask him a few questions for just a few minutes, but sadly the wish came two decades too late. All this is to say that the letter remained unanswered on my desk until my partner Helen heard about it, chastised me for my rudeness, and told me to write back. I did and suggested to this other Joseph Sassoon that we talk on the telephone, only to be mortified two days later when the porter proudly informed me that he had blocked what he thought was a prank phone call for me from a Joseph Sassoon. When I at last managed to speak to Joseph in Scotland, he told me about his father, the first cousin of the poet Siegfried Sassoon, and his grandfather, the husband of a prominent Gunzburg from Russia. Without his encouragement, I doubt this project would have taken off.

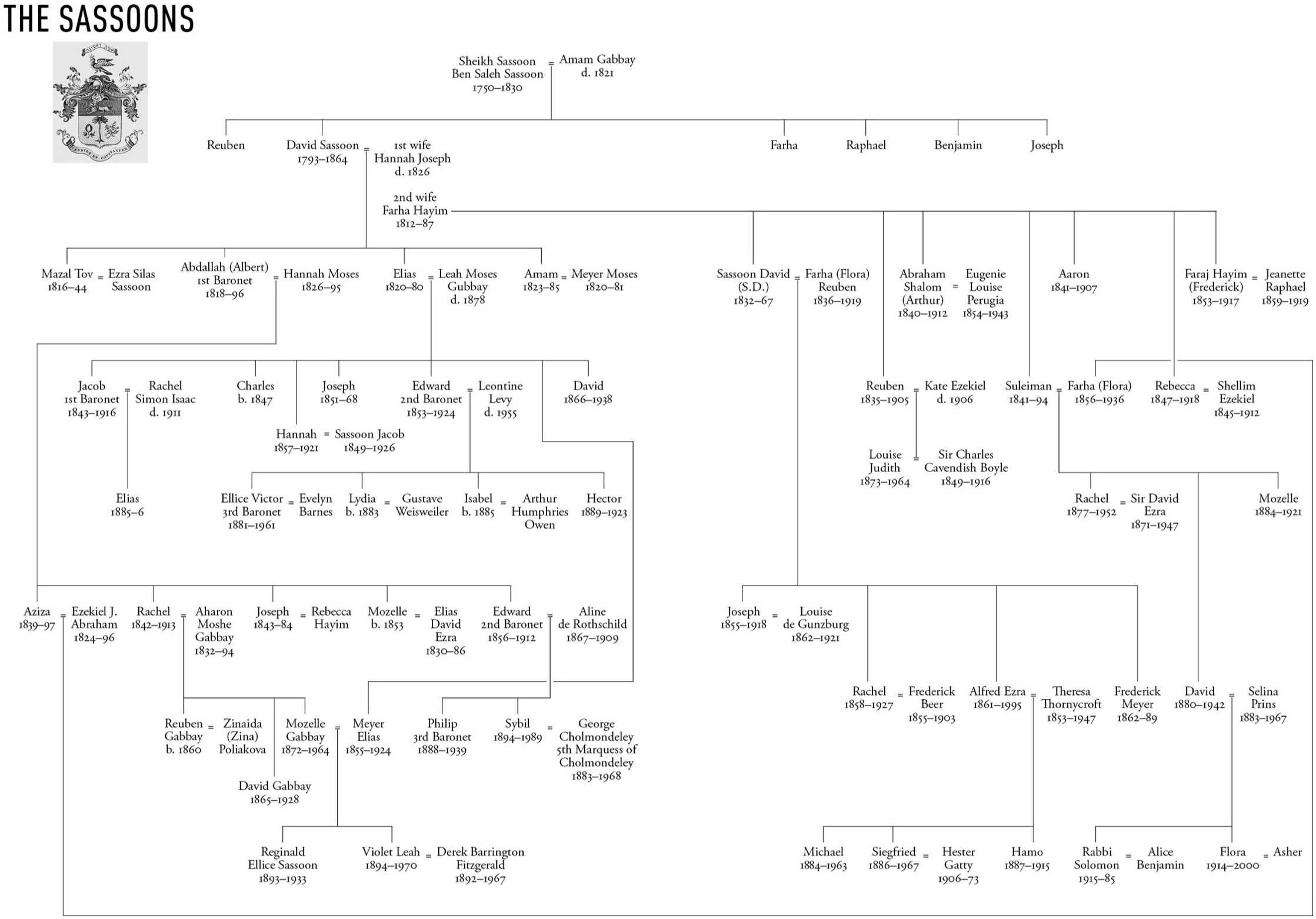

It was a subject with no relation to the book I had just finished, about the archives of Saddam Husseins Bath Party, or the one that had brought me to Oxford, a comparative study of authoritarian systems in the Arab republics, but my appetite was whetted. I visited the National Archives at Kew and the British Library in London to read about the family, and traveled to Scotland to meet Joseph (known as Joey). He shared with me what he knew and the trove of pictures that had been passed down to him. He also referred me to Sybil Sassoon, another family historian and the creator of a comprehensive family tree, stretching back to 1830, that would prove immensely helpfulnot least in distinguishing between other namesakes (unhelpfully for the researcher, the family favored just a few forenames, which recur within and across generations) and following individuals as they crossed continents in the age of empire, adapting their names as necessary.

I had no idea where these initial excursions would lead. Unlike Sybil, I was born too late to know any of the cast of this book, even the protagonists of the mid-twentieth century. And although I am descended from Sheikh Sassoon as Joseph hoped, he was the last ancestor we shared. When he fled Baghdad in 1830, fearing the wrath of the authorities, to join his oldest son, his other children remained in Baghdad. Some left Iraq later, but my ancestors stayed put until we too were forced to escape, for reasons similar to those of Sheikh Sassoon. After the Six-Day War in June 1967, life for the countrys Jews grew increasingly untenable. The rise of the Bath Party a year later exacerbated the situation, and public hangings of Jews followed in 1969. When we finally managed to escape a couple of years later, we left with nothing except for a small bag, closing the door not only on our property but on a land where my family had lived for centuries. This book is thus intended to be not a family history but the history of a family, specifically a branch with which I can claim a connection but of which I am not, in the end, a member.