Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

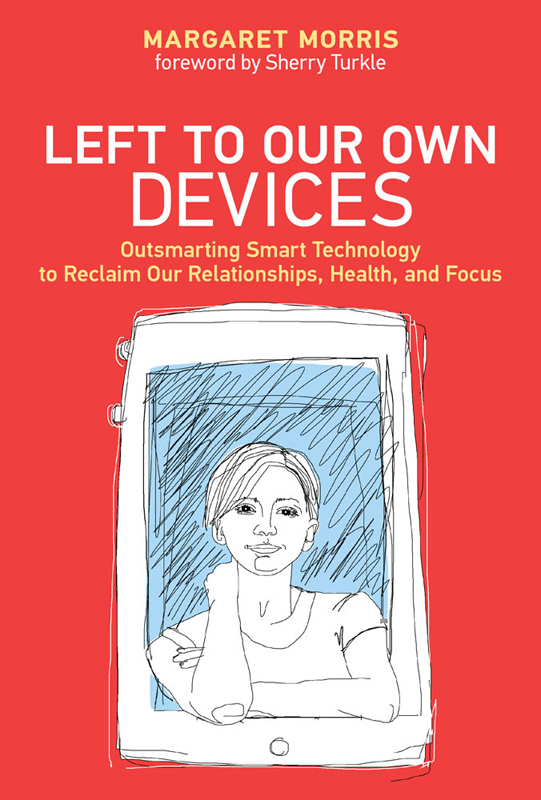

Left to Our Own Devices

Outsmarting Smart Technology to Reclaim Our Relationships, Health, and Focus

Margaret E. Morris

Foreword by Sherry Turkle

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Stone Serif by Westchester Publishing Services. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Morris, Margaret E., author.

Title: Left to our own devices : outsmarting smart technology to reclaim our relationships, health, and focus / Margaret E. Morris ; foreword by Sherry Turkle.

Description: Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018013341 | ISBN 9780262039130 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Internet in psychotherapy. | Internet--Psychological aspects. | Internet--Social aspects. | Health. | Interpersonal relations.

Classification: LCC RC489.I54 M67 2018 | DDC 616.89/14--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018013341

To my brother Michael, who has always pushed me to move forward

Contents

List of Illustration

Foreword

Sherry Turkle

Margaret Morris and I would seem to be on opposite sides of an argument. I am a partisan of conversation. Morris is a maestro of apps. Readers of this book will learn that this is too simple a story. In real life, when you take the time to look closely, we all talk back to technology. Or want to. The most humane technology makes that easy.

That puts a responsibility on designers. And on those of us who bring technology into our everyday lives. To make more humane technology, we have to make it our own in our own way. We cant divide the world into builders and users. Digital culture needs participants, citizens.

So if my plea to those who would build empathy apps has always been, We, people, present, talking with each other, we are the empathy app, both Morris and I would ask, Well, how can we build technologies that encourage that conversation?

For many years, I have written about the power of evocative objects to provoke self-reflection. But some objects, and by extension, some technologies, are more evocative than others. Left to Our Own Devices can be read as a primer for considering what might make for the most evocative technology. And if you suspect you have one in your hand, how might you best use it? You can reframe this question: If you are working with a technology that might close down important conversations, can it be repurposed to open them up?

Indeed, my first encounter with Morris was in June 2005, when she wrote me about a technology that I was already worried about.

The object in question was the robot, Paro, a sociable robot in the shape of a baby seal, designed to be a companion for the elderly. Paro gives the impression of understanding simple expressions of language and emotion. It recognizes sadness and joy, and makes sounds and gestures that seem emotionally appropriate in return. Its inventor, Takanori Shibata, saw Paro as the perfect companion for the elderly, and so did a lot of other people. After I visited Japan in fall 2004, Shibata gave me three Paros, and I began to work with them in eldercare facilities in Massachusetts. Thats what I was doing when I received Morriss first email. She said that she was a clinical psychologist interested in the health benefits of Paro. Shibata suggested that she be in touch with me. I look at that December 2005 email now and note my polite response: Yes, surely, lets talk.

I dreaded the conversation with Morris. I didnt have cheerful things to say to someone working on robots, health apps, and health benefits. The Paro project troubled me. Robots like Paro could pick up on language and tone, and offer pretend empathy to the elderly. But the robot understood nothing of what was said to it. Every day when I went to work, I was asking myself, What is pretend empathy good for?

One day my conflicts came to a head: an old woman whose son had just died shared the story with Paro, who responded with a sad head roll and sound. The woman felt understood. I was there with my graduate students and a group of nursing home attendants. Their mood was celebratory. We had gotten the woman to talk to a robot about something important and somehow that seemed a success. Yet in that so celebrated exchange, the robot was not listening to the woman, and we, the researchers, were standing around, watching. We, who could have been there for her and empathized, were happy to be on the sidelines, cheering on a future where pretend empathy would be the new normal. I was distressed.

So I approached my conversation with Morris thinking that perhaps I could be in dialogue with her as a kind of respectful opposition. But as soon as we met, it became clear that this would not be our relationship at all. Our conversations about Paro were not about any simple notion of benefits. She understood my concerns, and we moved to this: Were there examples from my research where robots had opened up a dialogue? How could the presence of humans with the robots help this happen? What are the situations where a human-technology relationship is mediated by a human-human relationship that brings people closer to their human truth? In the end, the pretend empathy of sociable robots is not a place where I was or am comfortable, but these questions were right.

And Morriss own work brought them to the foreground. I remember the first of her case studies that she discussed with me, where her presence had changed how a family experienced a social activity tracker. (The story she shared appears here as Family Planets in chapter 3.) An older woman was using the tracker. Her concerned daughter was in on the results. On the surface, the familys use of the tracker was instrumental: Could feedback from the social activity tracker convince the mother that more social stimulation was good for her?

In practice, the technology became a bridging device to open up a conversation between the daughter and her mother that the daughter did not know how to start alone. Now, with the app, the daughter found new words. The app had a display that showed her mother as a circle, an island that did not intersect with others. Now the daughter spoke of her mothers isolation as like being on an island, when everyone else youve known and loved has died. These were thoughts that the technology gave her permission to articulate. And Morriss presence, too, gave the daughter courage. Through the tracker, the daughter, and Morris, the daughter and the mother formed a bond; through the tracker, the daughter felt empowered because she had a scientist on her side. Morris helped the daughter interpret an independent view of her mothers isolation. It was nothing to be ashamed of. It was not an accusation. But it was not healthful, and people were here to help.

Here, the tracking technology was an evocative object for talking about feelings, an externalization, and its snapshot of the inner life facilitated new conversations. People are the empathy app, but technology can help them get more comfortable in that role