WERNERS

NOMENCLATURE OF COLOURS,

ADAPTED TO

Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Anatomy,

and the Arts,

BY P. SYME.

SECOND EDITION.

WERNERS

NOMENCLATURE OF COLOURS.

I had been struck by the beautiful colour of the sea when seen through the chinks of a straw hat.To day 26th. Lat 186 S: Long 366 W. it was according to Werner nomenclature Indigo with a little Azure blue. The sky at the time was Berlin with little Ultra marine & there were some cirro cumili scattered about.

CHARLES DARWIN

Zoological Notebook, Mar 26

WERNERS

NOMENCLATURE OF COLOURS,

WITH ADDITIONS,

ARRANGED SO AS TO RENDER IT HIGHLY USEFUL

TO THE

ARTS AND SCIENCES,

PARTICULARLY

Zoology, Botany, Chemistry, Mineralogy, and Morbid Anatomy.

ANNEXED TO WHICH ARE

EXAMPLES SELECTED FROM WELL-KNOWN OBJECTS

IN THE

ANIMAL, VEGETABLE, AND MINERAL KINGDOMS.

BY

PATRICK SYME,

FLOWER-PAINTER, EDINBURGH;

PAINTER TO THE WERNERIAN AND CALEDONIAN

HORTICULTURAL SOCIETIES.

SECOND EDITION.

EDINBURGH:

PRINTED FOR WILLIAM BLACKWOOD, EDINBURGH;

AND T. CADELL, STRAND, LONDON.

1821.

Contents

WERNERS

NOMENCLATURE OF COLOURS.

A NOMENCLATURE of colours, with proper coloured examples of the different tints, as a general standard to refer to in the description of any object, has been long wanted in arts and sciences. It is singular, that a thing so obviously useful, and in the description of objects of natural history and the arts, where colour is an object indispensably necessary, should have been so long overlooked. In describing any object, to specify its colours is always useful; but where colour forms a character, it becomes absolutely necessary. How defective, therefore, must description be when the terms used are ambiguous; and where there is no regular standard to refer to. Description without figure is generally difficult to be comprehended; description and figure are in many instances still defective; but description, figure, and colour combined form the most perfect representation, and are next to seeing the object itself. An object may be described of such a colour by one person, and perhaps mistaken by another for quite a different tint: as we know the names of colours are frequently misapplied; and often one name indiscriminately given to many colours. To remove the present confusion in the names of colours, and establish a standard that may be useful in general science, particularly those branches, viz. Zoology, Botany, Mineralogy, Chemistry, and Morbid Anatomy, is the object of the present attempt.

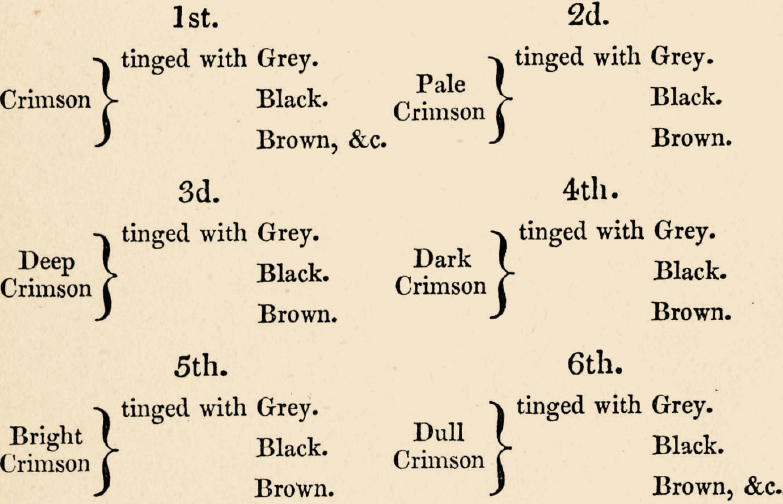

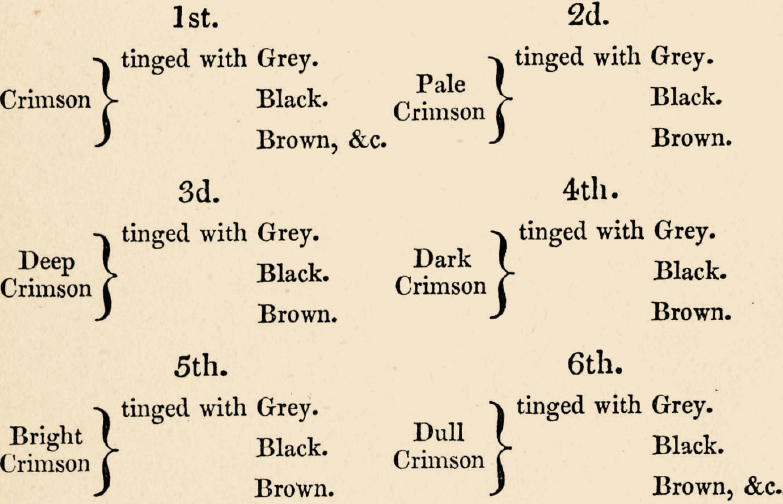

The author, from his experience and long practice in painting objects which required the most accurate eye to distinguish colours, hopes that he will not be thought altogether unqualified for such an undertaking. He does not pretend indeed that it is his own idea; for, so far as he knows, Werner is entitled to the honour of having suggested it. This great mineralogist, aware of the importance of colours, found it necessary to establish a Nomenclature of his own in his description of minerals, and it is astonishing how correct his eye has been; for the author of the present undertaking went over Werners suites of colours, being assisted by Professor Jameson, who was so good as arrange specimens of the suites of minerals mentioned by Werner, as examples of his Nomenclature of Colours. He copied the colours of these minerals, and found the component parts of each tint, as mentioned by Werner, uncommonly correct. Werners suites of colours extend to seventy-nine tints. Though these may answer for the description of most minerals, they would be found defective when applied to general science: the number therefore is extended to one hundred and ten, comprehending the most common colours or tints that appear in nature. These may be called standard colours; and if the terms pale, deep, dark, bright, and dull, be applied to any of the standard colours, suppose crimson, or the same colour tinged lightly with other colours, suppose grey, or black, or brown, and applied in this manner:

If all the standard colours are applied in this manner, or reversed, as grey tinged with crimson, &c. the tints may be multiplied to upwards of thirty thousand, and yet vary very little from the standard colours with which they are combined. The suites of colours are accompanied with examples in, or references to, the Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Kingdoms, as far as the author has been able to fill them up, annexed to each tint, so as to render the whole as complete as possible. Werner, in his suites of colours, has left out the terms Purple and Orange, and given them under those of Blue and Yellow; but, with deference to Werners opinion, they certainly are as much entitled to the name of colours as green, grey, brown, or any other composition colour whatever, and in this work Orange and Purple are named, and arranged in distinct places. To accomplish which, it was necessary to change the places of two or three of Werners colours, and alter the names of a few more; but, to avoid any mistake, the letter W. is placed opposite to all Werners colours. Those colours in Werners suites, whose places or names are changed, are also explained, by placing Werners term opposite to the name given, which was found more appropriate to the component parts of the changed colours. Those who have paid any attention to colours, must be aware that it is very difficult to give colours for every object that appears in nature; the tints are so various, and the shades so gradual, they would extend to many thousands: it would be impossible to give such a number, in any work on colours, without great expence; but those who study the colours given, will, by following Werners plan, improve their general knowledge of colours; and the eye, by practice, will become so correct, that by examining the component parts of the colour of any object, though differing in shade or tint from any of the colours given in this series, they will see that it partakes of, or passes into, some one of them. It is of great importance to be able to judge of the intermediate shades or tints between colours, and find out their component parts, as it enables us correctly to describe the colour of any object whatever.

Werners plan for describing the tints, or shades between colours, is as follows: When one colour approaches slightly to another, it is said to incline towards it; when it stands in the middle between two colours, it is said to be intermediate; when, on the contrary, it evidently approaches very near to one of the colours, it is said to fall, or pass, into it. In this work the metallic colours are left out, because, were they given, they would soon tarnish; and they are in some measure unnecessary, as every person is well acquainted with the colour of gold, silver, brass, copper, &c. Also the play and changeability of colour is left out, as it is impossible to represent them; however, they are well known to be combinations of colours, varying as the object is changed in position, as in the pigeons neck, peacocks tail, opal, pearl, and other objects of a similar appearance. To gain a thorough knowledge of colours, it is of the utmost consequence to be able to distinguish their component parts. Werner has described the combinations in his suites of colours, which are very correct; these are given, and the same plan followed, in describing those colours which are added in this series. The method of distinguishing colours, their shades, or varieties, is thus described by Werner: Suppose we have a variety of colour, which we wish to refer to its characteristic colour, and also to the variety under which it should be arranged, we first compare it with the principal colours, to discover to which of them it belongs, which, in this instance, we find to be green. The next step is to discover to which of the varieties of green in the system it can be referred. If, on comparing it with emerald green, it appears to the eye to be mixed with another colour, we must, on comparison, endeavour to discover what this colour is: if it prove to be greyish white, we immediately refer it to apple green; if, in place of greyish white, it is intermixed with lemon yellow, we must consider it grass green; but if it contains neither greyish white nor lemon yellow, but a considerable portion of black, it forms blackish green. Thus, by mere ocular inspection, any person accustomed to discriminate colours correctly, can ascertain and analyse the different varieties that occur in the Animal, Vegetable, and Mineral Kingdoms. In an undertaking of this kind, the greatest accuracy being absolutely necessary, neither time nor pains have been spared to render it as perfect as possible; and it being also of the first importance, that the colours should neither change nor fade, from long practice and many experiments, the author has ascertained that his method of mixing and laying on colours will ensure their remaining constant, unless they are long exposed to the sun, which affects, in some degree, all material colours; he has therefore arranged Werners suites of colours, with his own additions, into a book, and in that form presents it to men of science, trusting, that by removing the present ambiguity in the names of colours, this Nomenclature will be found a most useful acquisition to the arts and sciences.