Chapter 1

We choose our fate with the choices we make.

Gloria Estefan, song title

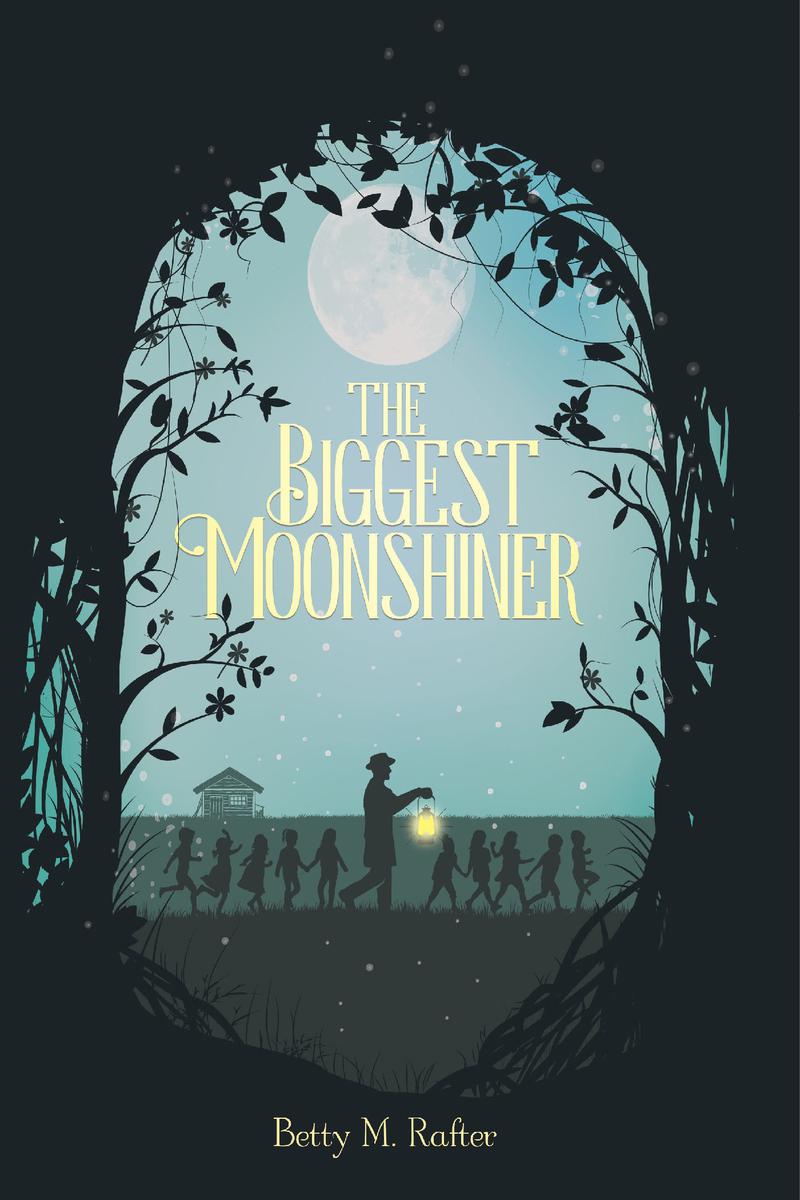

The Great Depression was starting to wind down in 1939, but not for us. On a frigid morning in Sopchoppy, Florida, ten days before Christmas, Mama, Daddy, my two older sisters, my two older brothers, our baby sister, and I were hiding out in a shack deep in the woods of the Apalachicola National Forest, south of Tallahassee. Daddy said we were on a fun adventure, but my oldest sister, Dink, said we were on the lam, running from the Feds.

My sister Lois, almost two years older than me at five, and I sat in homemade chairs pulled up close to a red-hot woodstove in the middle of a one-room tar paper shack, playing. Okay, my turn, she said. What color am I imagining? Our oldest sister, Dink, twelve, walked behind us with year-old Baby Bright Eyes bundled in her arms, singing Rock-a-bye Baby. My older brothers Robert and Mack, ten and eight, argued quietly about whose turn it was to bring in firewood from the frozen pile outside. A small pine tree in the corner, as far away from the stove as the parameters of the small room allowed, was draped with homemade strings of popcorn, dried red berries from the woods out back, and faded thin glass balls dangling on scant branches. There were no gifts beneath it.

Mama and Daddy were sitting across the room on a bench by the long, heavy homemade wooden table. She sighed and shrugged her shoulders. Urbie, we are almost out of groceries. She nodded toward the little Christmas tree, adding urgently, I need to do some shopping!

He said, We cant take a chance on you going into town, Shorty. Thats what he called Mama because she was only four foot eleven. You may get recognized. Make a list of what you want, and Ill get someone to do the shopping when I go to Jacksonville.

She scooted closer to Daddy and took a deep breath. She appeared to be explaining something else to him. Her fingers were tracing circles on the table as they spoke quietly.

He said, Dont worry, Shorty! As long as the kids are in the car, theyll never suspect anything around here.

But, Urbie, Im afraid they willwith the jugswhat ifthey catch us?

He slammed his fist on the table. I almost jumped out of my chair, and we all froze when he said in a booming voice, Damn it, Leila! I dont like it either, but we gotta do whatever it takes to put food on this table for you and these kids. He only called her, or any of us, by our real names when he was angrywhich was seldom.

Mama took a deep breath, pushed up from the table and put the jam away, wiped the crumbs from the table, and threw them into the fire. She took the baby from Dinks arms and said softly, You and Robert fold the quilts and put the mattresses against the wall, and well take your daddy to work.

I didnt want to leave the shack. With a roof over our heads and a floor under our feet, we were living in a mansion, after more than a year in abandoned houses with leaky roofs and no windows, or else in our army tent down by the river. Why, Daddy barely got our shack closed in before the onslaught of winter. A stack of rough slabs of lumber to cover the thick tar paper on the outside was stacked in an icy pile behind the shack, but it was warm inside. I was happy we no longer had to worry about the tent leaking when we touched the canvas or huddle around a fire outside or tuck ourselves under quilts in our straw beds to keep warm.

Mama bundled Baby Bright Eyes tighter. Mack, put a couple more pieces of wood in the stove to keep the fire going until we get back.

We all put on our coats, and Daddy swatted Mama on the bottom as she got to the door.

We piled into Daddys shiny new black V8 Ford. As we drove away from our shack, down the winding and bumpy dirt road, through the woods, Daddy started singing Little Brown Jug, and we all joined in. Log broke through, and I fell inbut I hung on to my bottle of gin

Urbie, I wish you wouldnt teach the kids songs about that stuff. There are a lot of other good songs to sing.

Okay, what do you want to sing, some of your church songs? Those were the only songs she was allowed to sing growing up in an evangelical home. She didnt answer him.

He started, Row, row, row your boat We kids joined him, singing in rounds.

As we turned onto the gravel road that led to the Ochlocknee River, Daddy hit the gas pedal. The car jerked, accelerating faster and faster. Mama, with Baby Bright Eyes in her arms, braced herself against the door and asked him to slow down. The trees became less distinct as we flew past them. Laughing, he turned toward my snickering brothers in the back seat and waggled his finger. You know, boys, this hot rod can outrun anything in Wakulla Countynot like our old truck.

As we approached the sharp curve in the road on two wheels, Mama pleaded, Urbie, please slow down. She held the baby closer, as I slid against her. He slowed the car and turned south onto a narrow path that meandered along the side of the rivers edge. The path was barely wide enough for the tires to avoid an occasional dip off the track onto the hard packed, muddy beach. Daddy dipped in and out of the water to tease Mama and thrill us kids. The sun was just coming up across the water, casting streaks of blazing orange and gold through the pines and illuminating the towheads piled in the back seat. We were laughing, enjoying the bouncy ride over the ruts and roots of the tall pine trees and magnificent hundred-year-old live oaks that formed a canopy overhead.

Following a dirt road overgrown with weeds, we suddenly took a sharp turn through a thicket of high brush that scraped both sides of the car and closed behind us.

Jip Jones, who lived in a shanty nearby, was already there. He had been working with Daddy since we left Alabama. We met him while picking cotton and hiding out near Dothan in the abandoned house where Baby Bright Eyes was born. Daddy asked him to join us and work for him. We left Alabama for Biloxi, where Daddy planned to truck farm, but we left there suddenly and somehow ended up in our tent by the river in Sopchoppy.

Robert waved to him. Mornin, Jip Jones.

He looked up and nodded, still shoveling. Hows dem chilren today? Mornin, Mista Urb and Missus Leila. He shoveled something from a barrel into a large copper container that looked like an oversize woodstove and added a piece of wood to the fire. A long, skinny, twisted copper pipe was connected to the top and extended into a wooden barrel with a tap at the bottom.

Jugs filled with clear liquid waited under the tree where Daddy parked by his old work truck with the fake floor in the back. Empty jugs sat on the ground behind the big stove. We stayed in the car while Jip Jones, Daddy, and Robert loaded the filled jugs of liquid into the trunk of the car. Mama handed the baby to Dink and walked around to the drivers side. She stood on tiptoes as she hung on to the open door and looked nervously in all directions. We lifted our feet as they loaded more jugs onto the front and back floorboards. Mama took a slow, deep breath as Daddy loaded the last jugs and covered them with an army blanket. Robert climbed over the jugs and closed the door, and Mama slid under the steering wheel. As he patted the front fender, Daddy told Mama, Well come home for dinner around noon. She nodded and slowly backed the car through the brush-covered opening, her gaze continually sweeping in all directions, as she drove back through the woods. She looked relieved as she parked the car close to the porch of the shack and turned off the engine.

_Jip_Jones,_Daddy,_helper,___Homer_1939.jpg)