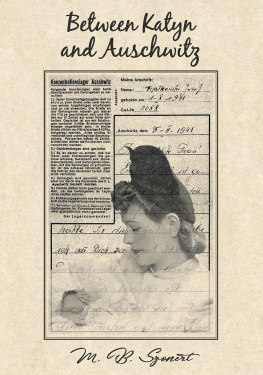

Between Katyn and Auschwitz

M . B. Szonert

Between Katyn and Auschwitz

Copyright 2019 by M. B. Szonert. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any way by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author except as provided by USA copyright law.

The opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily those of URLink Print and Media.

1603 Capitol Ave., Suite 310 Cheyenne, Wyoming USA 82001

1-888-980-6523 |

URLink Print and Media is committed to excellence in the publishing industry.

Book design copyright 2019 by URLink Print and Media . All rights reserved.

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-64367-977-8 (Paperback)

ISBN 978-1-64367-976-1 (Digital)

28.10.19

Contents

P olish nicknames are not just the shortened versions of the formal names. Frequently nicknames are longer and almost always contain softer consonants such as ni or and si or . Below are listed Polish names used in this book and their nicknames.

Alek Alu

Andrzej Jdrek, Jdru

Bronisawa Bronia

Danuta Danusia, Danu, Danuka, Danka

Eugeniusz Gienio

Janina Jasia

Jzef Jzek, Jzio

Maria Marysia, Maya

Regina Renia

Stanisaw Staszek, Sta

Zbigniew Zbyszek, Zby

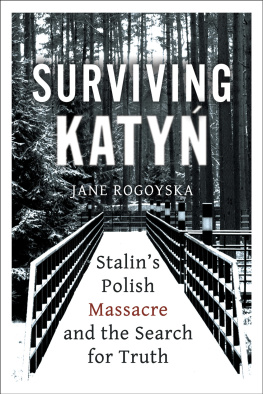

T he sympathy of the Western public opinion towards the Soviet Union had been growing steadily since the German attack on the Soviet Union, reaching its peak in early spring of 1943, after the Soviet victory at Stalingrad. During this pro-Soviet euphoria, the German Army stumbled over mass graves in the Katyn forest near Smolensk in Russia. The graves contained thousands of bodies of Polish officers in their military uniforms. The Goebbels propaganda machine rushed to announce the gruesome discovery to the world, naming the Soviets as the perpetrators of the crime.

The Polish Government in London called upon the International Red Cross to conduct investigation of the Katyn crime scene. Capitalizing on his favorable public image, Stalin labeled the Polish move as anti-Soviet and broke off diplomatic relations with the Poles. The Polish Prime Minister responded: Force is on Russias side, justice is on our side. I do not advise the British people to cast their lot with brute force and to stampede justice before the eyes of all nations. For this reason I refuse to withdraw the Polish appeal to the International Red Cross.

In the summer of 1943, the political tension over the Polish matter was at its peak. Polands Western allies found the Katyn affair most inconvenient. A perception was growing that the Poles were playing into the hands of German strategy. The United States treated the Katyn matter as a German attempt to divert international attention from the German losses on the Eastern Front.

In July of 1943, a plane carrying Polish Prime Minister Sikorski plunged into the sea over Gibraltar, instantly killing the Polish head of state and his only daughter but sparing the pilot. With Sikorski untimely death, Poland lost the most influential statesman, politician, leader, and patriot at the most critical moment for the countrys future.

The Roosevelt Administration was determined to contain the public debate over Katyn. British and American press consistently kept ignoring the Katyn subject but the issue represented an open wound for the Polish community. In 1944, President Roosevelt stepped up efforts to quarantine explosive debate over the Katyn massacre. The Polish-American radio stations received directives from Washington requesting restrain concerning sensitive issues like Katyn.

At the Nuremberg Trial the Katyn crime was also effectively contained. The victorious coalition chose the Soviet Union as the lead prosecuting nation with respect to crimes against humanity. This decision meant that the Katyn crime was to be submitted for prosecution to the Soviet Government, the suspected perpetrator of the crime.

After the demise of the Soviet Union, Boris Yeltsin presented the Polish Government with a top-secret document dated March 5, 1940. Signed by Stalin and the members of his Politburo, the document revealed that on Stalins order 14,700 Polish officers and 11,000 Polish government officials were executed in April and May of 1940. The Polish officers were murdered in three main locations: in the Katyn forest, in the NKVD prisons in Kharkov, and in the NKVD complex in Kalinin.

A t the twilight of her life, Danuta entrusted me with her dramatic life story. This book had been evolving over the period of several years, endless days, and countless hours of digging into Danutas remarkably vivid memory of the most brutal war ever fought. All the events and facts described in this story are true, and all the characters represent the real people with their real names. By the time the last chapter of this book was written, Danutas health deteriorated rapidly. She passed away on April 20, 2002, several months before the first edition of this book went to print.

She left us knowing, however, that the lessons of her tragic life would not be forgotten. Let us draw wisdom from her tragic life. Let us strive for a better understanding among the people and the nations. Let us always remember the price of senseless brutal war.

1. Katy Monument Over the Smoldering Ruins of the World Trade Center, Jersey City, New Jersey, September 11, 2001.

Prewar Warsaw

D anuta looks through the window of a suburban house. Its very beautiful here. Neatly cut grass and the strip of wild forest embracing a small creek surround a large deck decorated with baskets of perennials. It is very quiet here. In fact its so quiet that its too lonely. A few years ago, she and her sick husband moved to live with their son in this elegant suburban house in Ohio. It is very comfortable here. In fact its so comfortable that she has become lazy.

At the turn of the millennium, Danuta spends most of her time in the armchair, waking up only to check the mail and make phone calls. She cannot write anymore but loves to read letters and watch TV Polonia. Only recently, TV Polonia began to broadcast, directly from Poland via satellite, a regular Polish TV program for worldwide audiences. Danusia watches TV Polonia non-stop. It gives her and hundreds of thousands of other Polish people scattered all over the world some sense of belonging, a distant and abstract community of their own, more of a virtual or semi-imaginary world.

Breathing heavily, she slowly scuffs along towards her armchair, her face twisted from exhaustion. The glare of the television screen brightens the gloomy room. As she slumps into the chair, a sonorous voice abruptly awakens her consciousness.

On the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of the Katyn Massacre She turns around confused. What occasion? What anniversary? A young reporter from the TV Polonia Evening News yells from the screen. A special train carrying families of the Katyn victims arrived today at Katyn for the first official memorial ceremony. Danusia holds her breath, staring wide-eyed at the screen. The camera zooms on a newly erected memorial wall covered with thousands of small plaques listing the names of the Poles bestially murdered by the Soviets in 1940. This is my husband, a woman in her eighties cries out pointing to one of the plaques. Danusia hastily draws nearer the screen. You see, the woman continues, I was a happy wife for two years and a widow with two children for sixty years. This is a priceless moment in my life. I feel as if I am at last reunited with my husband. I brought with me today our two sons They are already in their sixties.

Next page