Table of Contents

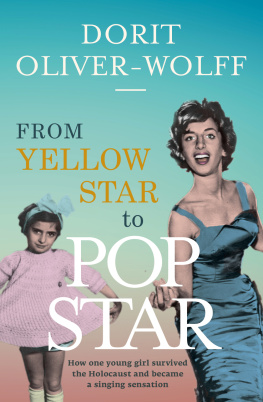

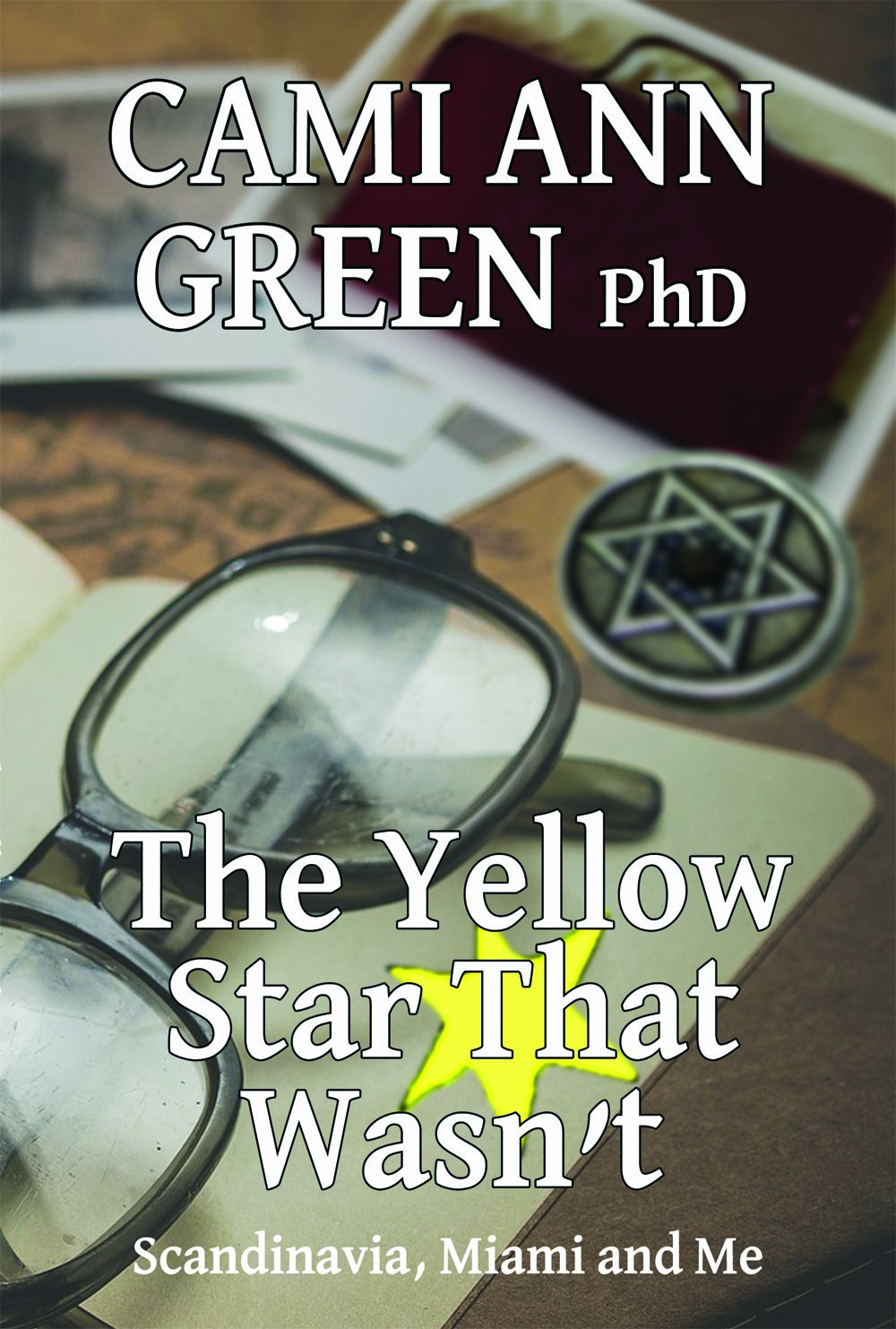

The Yellow Star That Wasnt

Scandinavia, Miami, and Me

WARTIME JEWS IN SCANDINAVIA FROM HELSINKI TO A MIAMI BEACH OBSESSION

CAMI ANN GREEN

AWARD -WINNING AUTHOR OF

HUMAN INTEREST STORIES

COPYRIGHT

The Yellow Star That Wasnt

Copyright 2020 by Cami Ann Green

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

For information contact :

Cami Ann Green

http://www .CHofstadter.com

Book and Cover design by Seagreen Press, LLC

First Edition: November, 2020

A FEW NOTES FOR THE READER

Although it may seem like the title of this book ( and Me ) should put it squarely in the genre of memoirs, I consider it a hybrid as it combines the historical facts of what happened to the wartime Jews in Scandinavia with my journey from Helsinki, Finland, where I grew up as a postwar, Protestant, Swedish-speaking girl living a life of illusion. The yearning to find a place to fit in has since taken me to Miami, Florida, the place where I first learned the truth about the King of Denmark and his Yellow Star.

In the words of Oliver Sacks, the famed neurologist and author, the human race is all about stories. Through them, we learn to understand ourselves and how to relate to each other. In the case of this book, the unusual anecdotes and turns of events, based in the later research I did to prepare for my talks about the fate of the wartime Jews in Scandinavia, also serve the purpose of teaching a multifaceted slice of history without overloading the reader with facts and statistics thatd only detract from the learning experience.

While the facts are true throughout the text, the imagined speech of the characters is an artistic device by authors of creative non-fiction (memoir). Unless equipped with a recorder, writers can only write about their own recollection or understanding of dialogues. Here, I may have an added advantage in that Im a lifelong diarist who frequently penned exact details of verbal exchanges.

The geographic area requires a brief explanation. An observant reader may notice that Iceland isnt included in what I alternatively call Scandinavia or the Nordic countries (although, historically, the two arent the same). This is because that island-nation didnt gain its independence from Denmark until 1944.

For any writer, style can be a dilemma. For me, the form for antisemitism was at first a problem: lower or upper case, hyphen or no hyphen? Should I let the correction feature of my word processing program dictate style, since it was so insistent on its own changes? For a variety of philosophical reasons, eloquently expressed by others, I finally decided to follow the usage by respected scholars: antisemitism .

As a reader of other languages than English (including Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish), I also faced the conundrum of the format for what the Nazis called the Judenfrage . While its one word in German (and Swedish, for that matter), its alternatively written in English with an upper or lower case for what then becomes the two-word term of Jewish Question or question. Since I found no consistency in my sources, including the website of Yad Vashem, I settled on the capitalized style.

Finally, although Andy was a very real person in my life, Ive changed his name here, as I did with all identifying characteristics of him and his family. Any resemblance to another person is purely coincidental.

Cami Ann Green

Miami, Florida

November, 2020

PROLOGUE

IN JANUARY 2000, amid man-sized piles of snow in Moscow, the Russian capital, I trudge up the steps to a brand-new activity center for Jewish seniors. Although Im living in Miami, Florida, a friend has arranged for me and my fiance, Andy, to be part of an eight-person delegation from the New York Joint Distribution Committee, a Jewish humanitarian assistance organization founded in 1914. It seems the rest of the group, all Jewish except me, hasnt made any special preparations for the visit either so I decide to just hang back and observe. On the way to the facility thered been an animated discussion about how to communicate with the people well visit, all members of a generation that usually doesnt know any English. None of us speaks Russian.

When one of the ladies says she knows a little Yiddish, rusty as it is since her parents passed away long ago, theres a communal sigh of relief. We have our default leader.

Were greeted by a group of perhaps thirty administrators and day residents, all of whom are visibly thrilled to show us, the amerikanskiy , the new building. We peek at tables set up with board- and card-games we dont recognize, we admire unfamiliar supplies lining open cabinet shelves, and we cluck over primitive craft projects. At the end of our tour, our hosts pour tea from a traditional samovar and hand us cookies on plastic plates festooned with a tiny white paper napkin so shiny and stiff that it doesnt even absorb a drop of liquid.

Our spokesperson, the only one in our group who can spout social niceties in Yiddish, makes an announcement. Now its their turn to ask questions of us, she says with an inviting smile. And, for extra emphasis, fregn, fregn ; ask, ask.

Theres an instant commotion among the men and women sitting on flimsy folding chairs along the edges of the room. Gesticulating to each other, they chatter in incomprehensible Russian. Finally, one lady, stout and in a drab well-worn blue dress, stands up.

Wagging her right index finger pointedly in my direction across the room, she calls out in Yiddish, Iz zi idishe? (is she Jewish?).

Without thinking, I shout across the room in my best German, Nein, ich komme aus Finnland. In Helsinki geboren (No, I come from Finland. Born in Helsinki). As if being from Finland precludes one from being Jewish.

But the babushka isnt taken back. She breaks into a big smile and, with an unexpectedly steady gait, scampers across the floor, throws her arms around me and plants kisses all over my face. For the rest of our visit she doesnt let go of my hand. The love between the Russian and Finnish people, Jews and Gentiles alike, runs irrevocably deep, in spite of a long history of wars and political strife.

Still, the sudden embarrassment from my uncharacteristic impulsiveness makes me wince. Had I really forgotten the voice of my forefathers with their still-prevailing social norms of never setting oneself apart in any way? Hadnt I learned anything from my mothers enduring admonishment dont think youre special that still rings in my ears, even now, decades after I left Helsinki for Miami?

Part 1 Yellow Stars

THE CRAYONED STARS of my childhood in Helsinki, Finland, where my life began in 1946, have five points. With my bright yellow crayon, Id press down on the somberly pitch-black sky so hard that the points of the stars practically bore holes through my coloring papers. Five points, always must be five . For this little Protestant girl, thats the way it is.

Till one day, crayons and paper before me at my two-seater wooden desk at school, I overlap two wobbly triangles and now my bright and shiny star has six points.

Thats not the way a Northern star looks like , my first-grade teacher says with a scowl.

The heat from the silent shame of doing something wrong slowly creeps up the sides of my face. Ill never draw another star in class again. Only in our cramped four-story walk-up, where my sister and I share a tiny bedroom, will these sparkling symbols of something good continue to illuminate my vision of a happy life to come, just like in picture books and fairytales.