Introduction

Introduction: Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained

Claremont Village, a New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) public housing development built in 1963, is located in the Morrisania section of the South Bronx and is one of the oldest and largest public housing projects in the USA. Claremont Villages estimated 12,000 residents live in four adjoining projects: Butler, Morris, Webster, and Morrisania Houses. The median income is $30,498, and in 1977 in New York City, there were 154,087 violent crimes, 1,919 murders, 57,193 aggressive assaults, 5,272 rapes, and 89,703 robberies. This is the neighborhood where I grew up.

It was the summer of 1977, Wednesday, July 13, 5:36 p.m., when all the lights went out in all of New York City, including the South Bronx. During this same period, a serial killer roamed through the city looking for brown-haired women. Billy Martin and Reggie Jackson almost came to blow at Yankee Stadium, and throughout the night, mayhem ruled the city with looting, arson, and property damage in every borough.

I was a twenty-two-year-old African American male New Yorker with a growing sense of identity, skepticism, and curiosity about the future. Shortly thereafter, I learned there was no electricity in the entire city of New York, including the South Bronx where I lived. The next day with no electricity anywhere in the city, I recalled the blackout of 1965, and not knowing what to expect, I decided to walk the three blocks from my home to Bathgate Avenue, where most of the merchant clothing and appliance stores were. As I walked, I could feel something strange going on. There were not many cars on the road. No traffic lights or signals were working. It was eerily quiet. I imagined most people preferred to stay in their homes out of sheer confusion or outright fear until the power came back on. Once I crossed the street, where the merchant stores were, I could see several individuals running toward me. Their arms filled with clothing and appliances they had looted from the shops. I am not quite sure what motivated me. Perhaps it was just the opportunity of being at the right place at the right time. However, I decided to enter one of the stores and joined in the looters grabbing items of clothing off the racks.

This fortuitous opportunity, however, was short-lived. After entering the store, I heard an unfamiliar booming voice shout, Everyone freeze! Put the merchandise down! Youre all under arrest!

I turned to see where the voice was coming from, and there in the doorway of the store stood three huge White police officers, including a sergeant, blocking the entrance. The officers immediately began handcuffing the startled looters as they quickly attempted to make their way to the rear exit doors. I panicked and immediately began to consider a justifiable excuse that I hoped would prevent me from being arrested. After all, I was not a common looter but a circumstantial thiefsomeone looking for something to steal, taking advantage of a unique opportunity on this special occasion.

At least, thats how I perceived this moment in my mind. After a while, the police sergeant got on his bullhorn and announced that the remaining looters, including me, must leave the premises and merchandise immediately. We were free to go but only because they had no more room in the police cars, vans, or local precinct holding cells. It was a huge relief to learn that all the jail cells were completely full, and I got off scot-free.

I look back on that day and remind myself often how fortunate I was because I didnt consider myself a thief necessarily. I had never considered spending time in jail or even thought about what it must be like, and I certainly did not want to ever find out.

To this day, I am truly grateful for that divine intervention.

I had worked hard two years earlier and graduated from De Witt Clinton HS, located in the North Bronx, in 1975. About six months after graduation, I applied for and got a job working in the mail room at a rather large malpractice law firm in Manhattan called Boumen and Gartner. At that time, it employed 135 attorneys and almost as many support staff housed on three floors in their offices on Madison Avenue.

It was a good job for a young African American just out of high school. It felt good to be around educated people who had acquired law degrees and were actively litigating hundreds of legal malpractice cases.

One year after I began working in the mail room, I learned the law firm sponsored an apprenticeship program for young men and women entering the workforce to become paralegals. I applied optimistic about the chance to do something other than being stuck in the mail room, hoping to learn more about malpractice law and opportunities for advancement within the company. After all, I was still living with my mom, commuting on the subway, and eating the same affordable lunch every day: two hotdogs or pizza slices and a soda for $3.50.

After several months had passed and I had not heard from the human resources department, I decided to inquire about the status of my application with the court calendar clerk, Charlie OHanlon, a retired firefighter, who I was told to give the application to and I was quite friendly with at Boumen and Gartner. Charlie had seemed to be avoiding me lately for some strange reason. About three weeks later, while working late, I spotted Charlie in his office and ran over to him.

Hey, Charlie, hows it going? I said in an upbeat mood.

Oh, just fine, Ivan. How are you? Charlie replied while looking at his files.

Fine, sir. I was just wondering about my application that I submitted for the apprenticeship paralegal program.

All of a sudden, Charlies face went beet red and changed into a serious frown. He informed me the firm was not interested in supporting my application. He was, it seemed, too embarrassed to tell me they had no intention of sending a young Black male employee from the mail room into an apprenticeship program for paralegals geared toward any kind of upward mobility. Certainly not at this law firm.

Despite being stung and naive by that reality, I continued working at the law firm for three years after that insulting incident. I also was actively seeking other career opportunities. I guess looking back now, I just was grateful to have a job.

That same summer of 1977, my sister was dating an NYPD detective named Arnold Webster, who would later become my brother-in-law. At that time, the New York City police force did not employ many African Americans. Except for Arnold, I was not remotely interested in having a conversation with any police officer about career opportunities. Based on what I knew, which was very little, it seemed that the likelihood or probability of anyone from my neighborhood becoming a police officer was extremely low.

As an African American male living in the South Bronx in the seventies, this was our realityit was common knowledge, and we understood it clearly. The police only came to our neighborhood when something bad happened. We didnt know them. They didnt want to know us, and we certainly didnt trust them. They had no interest in getting to know anyone in our community other than to gather information about a suspects whereabouts to make an arrest.

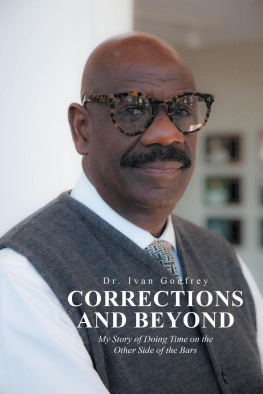

However, in a conversation with Arnold, he suggested to my sister that we both should apply for a civil service exam with the NYS Department of Corrections. First off, I did not have the slightest idea what a correction officer was, what they did, or why anyone would even consider taking the job working inside a prison . However, after some gentle nudging from Arnold, my sister and I applied to take the exam partly as a gesture to appease Arnolds misguided ambitions for us both and partly out of my morbid curiosity.