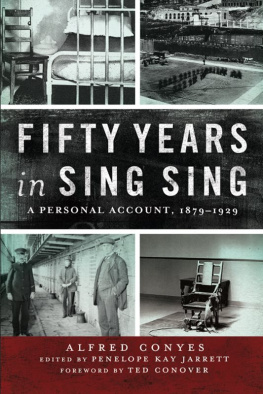

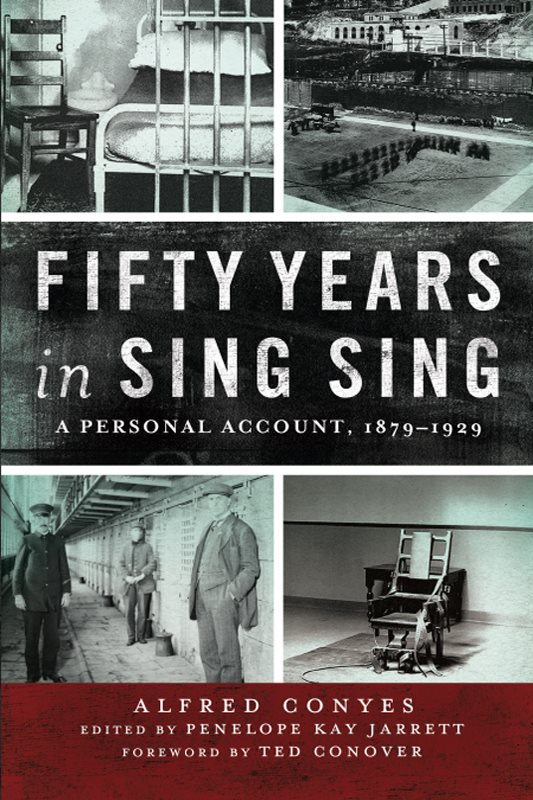

Fifty Years in Sing Sing

Fifty Years in Sing Sing

A P ERSONAL A CCOUNT , 18791929

ALFRED CONYES

Edited by

P ENELOPE K AY J ARRETT

Foreword by

T ED C ONOVER

State University of New York Press

Albany, New York

Published by

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS

Albany

2015 Penelope K. Jarrett, Pamela Jean Jarrett,

Robert Vincent Jarrett, and Lauren Gail Jarrett

Foreword Ted Conover

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Excelsior Editions is an imprint of State University of New York Press

For information, contact

State University of New York Press

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Laurie D. Searl

Marketing, Fran Keneston

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Conyes, Alfred, 1852

Fifty years in Sing Sing : a personal account, 18791929 / Alfred Conyes ; edited by Penelope Kay Jarrett ; foreword by Ted Conover.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5422-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4384-5424-5 (ebook)

1. Conyes, Alfred, 1852 2. Sing Sing PrisonHistory. 3. Correctional personnelNew York (State)Biography. 4. PrisonersNew York (State)History. 5. CorrectionsNew York (State)History. I. Jarrett, Penelope Kay, 1954 II. Title.

HV9468.C66A3 2015

365'.6092dc23

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the memory of my great-grandfather, Alfred Conyes, to the wardens, keepers, and guards he worked with, to the tens of thousands of prisoners who served time at Sing Sing Prison during his fifty years of service, and to Alfred Van Buren, Jr., who transcribed the original manuscript dated 1930.

Contents

by Ted Conover

by Lewis Lawes

Illustrations

Foreword

Guards know the world of prison intimately, yet few have written books. My Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing was based on a ten-month passage through that storied institution in the late 1990s, which I sought in order to be able to write about the job; it is a rookies chronicle.

Alfred Conyess memoir is at the other end of the experience spectrumhe wore the guards uniform for more than fifty years, the very definition of veteran. This account of that career, committed to paper by a relative in 1930 and never before published, holds interest in part because it spans so many of the most tumultuous years of American penal history. Conyes was an eyewitness to and participant in practices which are no more: harsh physical punishments such as dangling a prisoner on a peg by his handcuffs; forcing prisoners to work twelve-hour days in prison shops for outside contractors; double-bunking prisoners in cellblocks made of stone, with little fresh air and no plumbing; frequent changes of politically-appointed wardens in the days before prison jobs became professionalized; hangings for capital cases in New York, and the frequent use of Sing Sings electric chair that followed the change to electrocution; and constant attempts at escape, including via the Hudson River.

He was also witness to one of the most daring experiments in American penal history, the prisoner-run Mutual Welfare League, established by the reformer Thomas Mott Osborne during his tenure as warden. And he had the good fortune to spend the last ten of his fifty years in the administration of Lewis Lawes, another famous reformer. Lawes (who, like Conyes, began his prison career as a guard at Clinton Prison in Dannemora, New York) became warden in 1920 and worked tirelessly to keep his prison in the public eye and present his prisoners as human beings, hosting a radio show, appearing on newsreels, inviting major league sports teams to play at the prison (sometimes against inmate teams) and cooperating with Warner Brothers in the production of movies such as Each Dawn I Die and Angels With Dirty Faces . Lawes wrote several books as well as a brief foreword to the present volume.

Conyes summarizes Sing Sings remarkable history up to his employment, and he quotes numerous newspaper accounts of famous executions and escapes; the most engaging of these are supplemented by his personal knowledge. He was given a special assignment, for example, to guard Martha M. Place, the first woman to be electrocuted in New York, in the days leading up to her date with the chair. Place had suffocated her stepdaughter, struck her husband on the head with an axe, and attempted suicide all on the same day in 1898. Assigned to do guard duty outside her door, Conyes writes, I was told to keep a close watch as the time for her execution was drawing near and the warden wanted to be sure that she did not kill herself and beat the chair.

Conyes angered Place by forbidding her to use a staircase she had exercised on, saying she could easily have thrown herself down the steps. On the day of her execution, however, she asked whether he could be the one to strap her into the chair. He writes:

Now, I had seen many men die in the chair but the idea of strapping a woman into it was something different.

Taking her arm, I escorted her down the steps, across the prison yard and into the death house. Behind us walked the warden, two keepers, a woman physician, Mrs. Places spiritual advisor, the Reverend Dr. Cole of Yonkers, and one of the prison matrons. The doomed woman was attired in a black gown which she had made to wear at an expected new trial. Having failed to get such a trial, she asked Governor Roosevelt to commute her sentence to life imprisonment but the petition was refused.

I quickly attached the electrodes after strapping in her feet. So great was the modesty in those days that a woman attendant spread her skirts before Mrs. Place so that the witnesses could not see her ankle as the electrodes were put into place against her calf. After strapping her arms down and tightening the broad belts across her chest, I stepped back and signaled the warden that all was ready.

The clergyman walked quietly away from the chair just before the current was turned on. The body scarcely moved. The prayer book in the womans left hand twisted across the wrist and slipped partly out as the muscles relaxed. Her thin lips simply tightened with the shock. The matron told me afterward that Mrs. Place had requested that the prayer book be given to me. Naturally, it is one of my most prized mementos.

The most valuable parts of this book, to my eye, are the passages in which Conyes recounts personal incidents that cast light on what his job was like. It is well-known, for example, that prisoners during the early years of his tenure had to wear striped uniforms (to facilitate their capture should they escape) and march between buildings in lockstep, one hand on the shoulder of the man in front, eyes straight ahead, in silence. But never before have I read an account of how a guard responded when a prisoner broke that rule. (I had overlooked it once in a while because it helped keep up the morale of the men. As in other cases, they took advantage of this until they had overdone the privilege, so I told them that there would be no more talking. One of the men paid no attention and his constant babbling got on my nerves.) Conyes describes in detail how he handled that vexing case and the aftermath.