The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

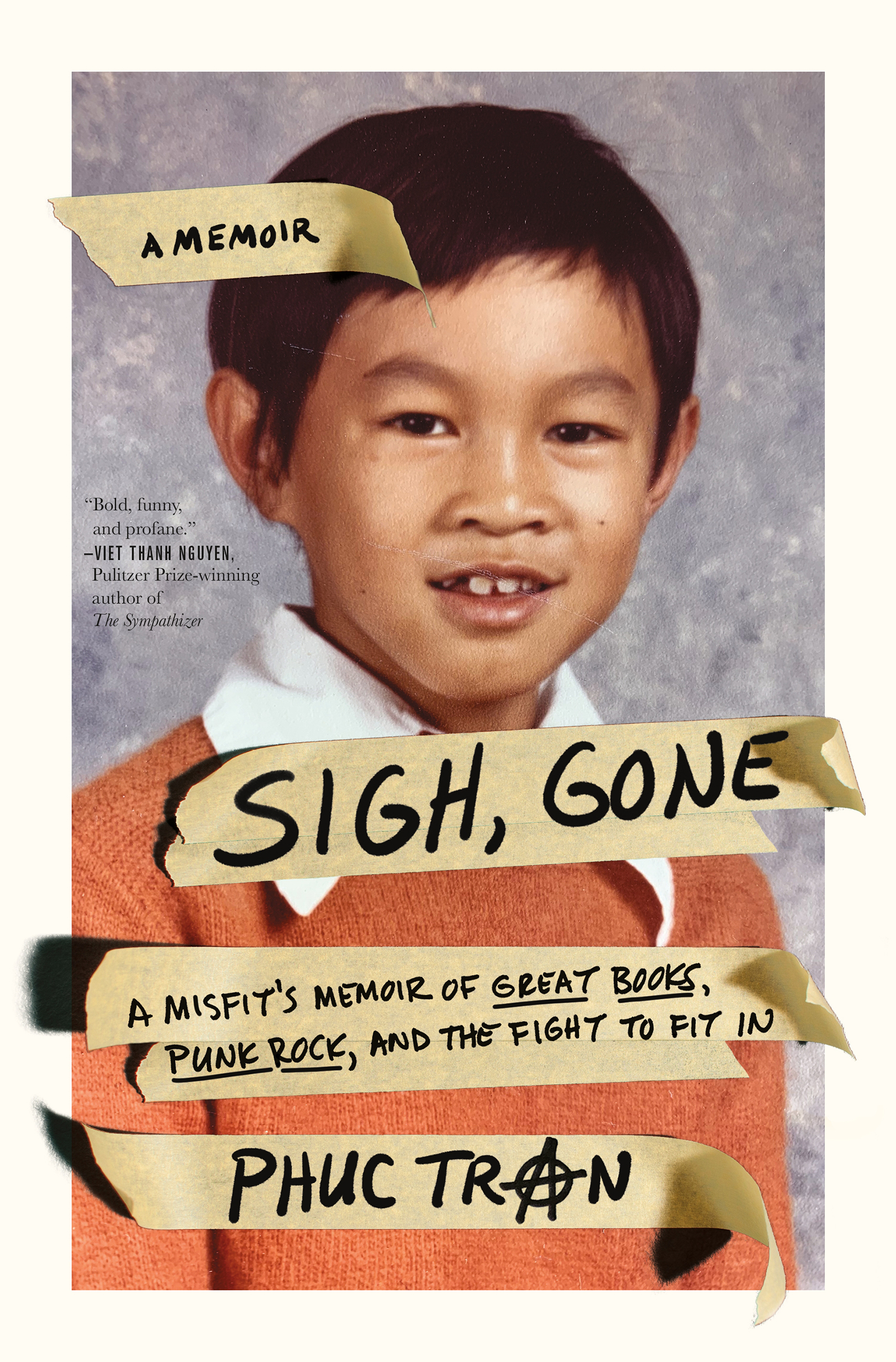

Fuck that kid.

Thats what I thought when I first saw Hong Nguyn in eleventh grade. Hong never did anything to me, and he certainly never said anything to me. God, he hardly looked at me except when we passed in the hallways, me on my way to physics, him on his way to wherever. Wed glance at each other, give a quick nod, and move on, swept along in the rapids of our hallways. But fuck that kid.

Hong was a fun-house mirrors rippling reflection of me, warped and wobbly. I hated it. I was Dorian Gray beholding his grotesque portrait in the attic, and I was filled with loathing. My disgust for Hong was complicated and simple at the same time: I was the Vietnamese kid at Carlisle Senior High School. Just me. Fuck that new Vietnamese kid.

Nestled in the Susquehanna Valley town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Carlisle Senior High School sprawled as a monolithic mid-century modern block of types: archetypes and stereotypes. Industrial gray lockers ringed its hallways, the compartments narrow enough to repel most of your textbooks but wide enough to collect the trash and detritus from your backpackyour own personal landfill. Linoleum floors, classrooms with chables (the combo chair-tables of the seventies), blackboards, American flags, loudspeakers from which the wah-wah-wah of adultspeak would drone. Our school district was so large that the juniors and seniors had their own separate high schoolthe so-called Senior High Schooland the freshman and sophomores had their own underclassmen high school building.

Carlisle High School stocked its seats and bleachers with a familiar cast from the eighties: the athletes who towered above the rest of us; the cheerleaders who lay supine beneath them; the geeks with their physics books under their arms; the preps with their Tretorns, Swatches, and impeccable Benetton sweaters; a handful of black kids with MC Hammer pants and tall, square Afros, tightly faded; punks and skaters with their leather jackets and black Converse; a few swirly hippies; the rednecks with their oily palms and cigarettes and trucks. Carlisle High School was another cultural cul-de-sac built with the craftsman blueprint of John Hughes, the Frank Lloyd Wright of teen malaise.

Overwhelmingly white, Carlisles population offered all the rainbows of Caucasia. The towns main employers were Dickinson College, the Army War College, a smoky stack of factories, and the service industries that had sprung up to support the aforementioned trifecta.

In the spirit of public education, we progeny were all in the mix together: the itinerant army brats; the ivory sons and daughters of professors, doctors, and lawyers; the greasy offspring of waiters, cooks, and factory workers; and the token refugee family. The Trn family blended right into the mix like proverbial flies in the ointment. That is to say: we didnt.

Carlisles glitter was unmistakably eighties, but its structure was straight from the postwar era, bricked together by the mortar of the fifties. We had a downtown Woolworths with a chrome luncheonette counter and red vinyl stools and a grand movie theater with its incandescent marquee. The four corners of Carlisles town square were righted by two courthouses and two churches (Episcopalian and Presbyterian). God and Law and Law and God. It wasnt a subtle message to any of us living in Carlisle what was at the heart of the town.

And the pice-de-rsistance: our high school was the towns designated Cold War fallout shelter. The blue-and-yellow radiation placards festooned our hallways, reminding us that we were only a button-push away from nuclear annihilation.

From what I gleaned on television, Carlisle seemed like a slice of American pie la mode. We bottled lightning bugs on summer nights. Trucks flew Confederate flags. We loitered at 7-Elevens and truck stops. We shopped at flea markets and shot pellet guns. My high school provided a day care for girls who had gotten pregnant but were still attending classes. We stirred up marching band pride and fomented football rivalries. The auto shop kids rattled by in muscle cars and smoked in ashen cabals before the first-period bell. We were rural royalty: Dairy Queens and Burger Kings.

This was small-town PA. Poorly read. Very white. Collar blue.

So where did the immigrant Vietnamese kid fit into all of this?

By junior year, I had spent the last eleven years of school clawing my way to acceptance, at least in my own mind. As the only Asian kid in my classes and school through eighth grade, and then one of the very few in high school, I had been taunted and bullied in those early years. The blatant playground racism I bore in elementary school dipped below the surface in middle and high school, but it was always rippling under the social currents.

I believed that I was bullied because I was Vietnamese, so I did the math for my survival: be less Asian, be bullied less. Armed with this simplistic deduction, I tried to erase my otherness, my Asianness, with an assimilationan Americanizationthat was as relentless as it was thorough.

My plan for assimilation was a two-pronged attack, top-down and bottom-up. The top-down assault was my attempt at academic excellence. In the trenches of high school warfare, honor roll and National Honor Society shielded me: even if I felt like a social pariah in my classes, at least I would have a better vocabulary than these philistines.

I realized that there was some prestige in being smart, or at least appearing smart. Sounding smart was not the same social Teflon as being good-looking or athletic or funny, but hell, if someone could give me some props for being good at school, I would take nerd props over no props at all. I got zero props for being Vietnamese or bilingual or a refugee. Operation Sound Smart commenced: I read voraciously, I studied tirelessly. I read as much (or at least name-dropped as much) of the Western literary canon as I could. Of course, I was a teenagerwhat the hell did I really know?but my drive was as tenacious as my ignorance was deep. Being an intellectual gave me some clout in the classroom. And basking myself in the esteem of my classmates, I felt the warmth of their respect in sharp contrast to my cloaked envy of them. They belonged in a way that I never could, and their regard for me was sweet and sour. How Asian.

Then I hit the jackpot. Triple cherries. Working at my towns public library as a library page, I bought a discarded copy of Clifton Fadimans The Lifetime Reading Plan.

In The Lifetime Reading Plan, Fadiman listed and summarized all the books that he thought educated, cultured Americans should read over their lifetime, beginning with the Bible and ending with Solzhenitsyn. The Plan listed the books and presented Fadimans synopses of the books merits and his justification for their obvious place in the Western canon. His introduction was unapologetically American, classist, and whiteand I loved it. The Plan would be the most powerful cannon in my war for assimilation.