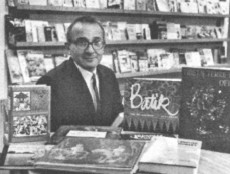

Most people are surprised to learn that the world's largest publisher of books on Asia had its beginnings in the tiny American state of Vermont. The company's founder, Charles E. Tuttle, belonged to a New England family steeped in publishing. And his first love was naturally booksespecially old and rare editions.

Immediately after WW II, serving in Tokyo under General Douglas MacArthur, Tuttle was tasked with reviving the Japanese publishing industry, and founded the Charles E. Tuttle Publishing Company, which thrives today as one of the world's leading independent publishers.

Though a westerner, Charles was hugely instrumental in bringing knowledge of Japan and Asia to a world hungry for information about the East. By the time of his death in 1993, Tuttle had published over 6,000 books on Asian culture, history and arta legacy honored by the Japanese emperor with the "Order of the Sacred Treasure," the highest tribute Japan can bestow upon a non-Japanese.

With a backlist of 1,500 titles, Tuttle Publishing is more active today as at any time in its pastinspired by Charles' core mission to publish fine books to span the East and West and provide a greater understanding of each.

Chapter One

The Origin of Sinawali

Queng lean queng tigre ecu tatacut, queca pa?

(Translation: I fear neither lions nor tigers,

why should I be afraid of you?)

PAMPANGA WARRIOR'S MOTTO

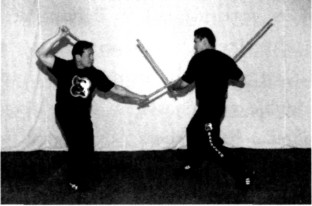

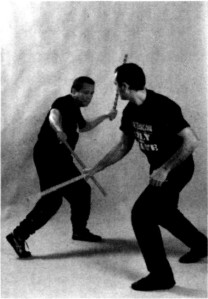

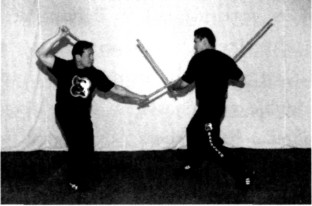

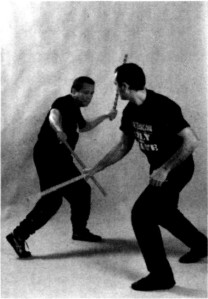

Pampanga, an area that once encompassed a large portion of the Central Luzon Plain of the Philippines, has always prided itself in its renowned leaders and heroes; the courage, skill, and loyalty of its warriors, and its fighting art, known as Sinawali (literal translation: woven), a proven combat art noted for its advanced and sophisticated double-weapon system of fighting. Contrary to popular belief, the art of Sinawali is not exclusively a double-weapon system, but also includes the use of single weapons, knives, and the long pole, or pingga. The present borders of Pampanga were established in 1873, after various sections of the old Pampanga region were incorporated into the provinces of Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, and Tarlac.

The highly advanced method of double-weapon fighting unique to this area has been variously attributed to Malay, Chinese, Japanese, and Muslim influences. Historically, any or all of the sources mentioned could be traced, studied, and verified. One thing, however, remains unique, and it is that a double-weapon system of training and fighting has never been developed elsewhere to the degree of sophistication and structure as found in the art of Sinawali. History will also show why Pampanga, an area now known for its agriculture and commercial strength, was once the source of much-sought-after, courageous, and proven mercenary fighters and an equally fierce fighting art.

Archaeological evidence suggests long-standing links between Pampanga and the outside world, both with nearby regions and with Chinese merchants plying the Philippine coastal and river trade. An early Spanish account concerning the Pampangans and the neighboring Tagalogs reported that "they are keen traders, and have traded with China for many years, and before the advent of the Spaniards, they sailed to Maluco, Malaca, Hazian, Parani, Brunei and other kingdoms." Pampangans were recorded to have traveled to Batavia as late as the first half of the seventeenth century, even after the arrival of the Spaniards. With the influence of the Spanish trading orbit of Manila, they ceased their seafaring ways in 1650 and thereafter became almost exclusively an agricultural and commercial people. The influence of the Chinese arts and sciences contributed much to the development of Pampanga. Panday Pira, a well-known Filipino blacksmith and a resident of Pampanga, was famous for his skill in metal-working and in casting cannonssciences that were gleaned from the Chinese. Elements of the Pampangan language and family dynasties can be traced to Chinese influence and presence in the region. Family surnames ending with "co," such as Songco, Gocheco, and Cojuangco, to mention a few, are manifestations of the presence and growth of the Song, Go Che, and Co Juang families in Pampanga. The language also reflects its assimilation of the Chinese language. The term a chi in Chinese is atchi in Pampango and is used in both languages to address an elder sister. The same term is ate in the Tagalog regions.

The Pampangan language, Pampango, appears to have been influenced primarily by the Malay-Polynesian family of languages, and, according to David Paul Zorc of the Australian National University, it belongs to the Proto-Sulic branch of the Filipino languages. It is believed to be a transitional language between the Northern and Southern groups. Brother Andrew Gonzales of De la Salle University, Philippines, states: "Pampangan shares certain phonological features with Pangasinan and Sambal, likewise transitional languages."

Pampango food terms, the origins of which can be traced from the trade intercourse with Batavia (now Jakarta), Malacca, the Moluccas, and other Malay settlements, show that Sulipan (Apalit) was an early Malay and Muslim settlement. The terms nasi (rice) and babi (pork) are common among Malay-Polynesian languages. The term mangan (to eat) is the same in Sulawesi and is makan in Bahasa Malaysia and Indonesia.

At least one community, Lubao, was deemed by the Spaniards to have come under the influence of the Muslim thrust from the south. An official Spanish report published in 1576 states: "[Pampanga] has two rivers, one called Bitis [Betis] and the other Lubao, along whose banks dwell three thousand five hundred Moros, more or less, all tillers of the soil." Other reports suggest that Muslims may have inhabited Betis and Macabebe as well. In 1571, a force from Macabebe led by their own datu (chief), fought against the Spaniards in Tundo. Rowing down the waterways from Macabebe and Hagonoy to Tundo with several hundred warriors on board twenty or thirty paraos, the datu jeered at Lakandula and Sulayman for having submitted to the puting mukha (white faces), as he contemptuously referred to the Spaniards. Refusing the offer of peace and friendship from Legazpi, the datu fought valiantly against the Spaniards in the bay of Bankusay The great Macabebe datu led the opposition and bravely, albeit foolishly, sat at the prow of the leading vessel and was killed by the first volley of the enemy's cannons.

In later years, the Spanish conquistadors skirted the communities of Betis and Lubao and pacified them only after the rest of the province had fallen. This military challenge to the Spaniards may well have resulted from the Islamic presence and influence in those towns.

Recognizing the courage and fighting abilities of the Pampangan natives, the Spaniards recruited local soldiers, who were soon to become both admired and derided as the Macabebe Scouts. Many Pampangans from the town of Macabebe served as volunteers in the colonial army alongside the traditional Pampangan mercenaries who remained in the pay of Spain. In 1574 these and other Pampangan soldiers, armed with rifles and the ubiquitous bolo, were to fight side by side with the Spaniards to repel the attacks of the Chinese pirate Limahong. Don Juan Macapagal earned Spanish praise and trust when he became instrumental in suppressing the woodcutters' revolt of 1660. He was asked by the authorities to lead (as Master of the Camp) a Pampangan contingent against the threatened invasion by the Chinese pirate Koxinga in 1662. Macapagal was later awarded an enconomienda by the king for his long and faithful service.