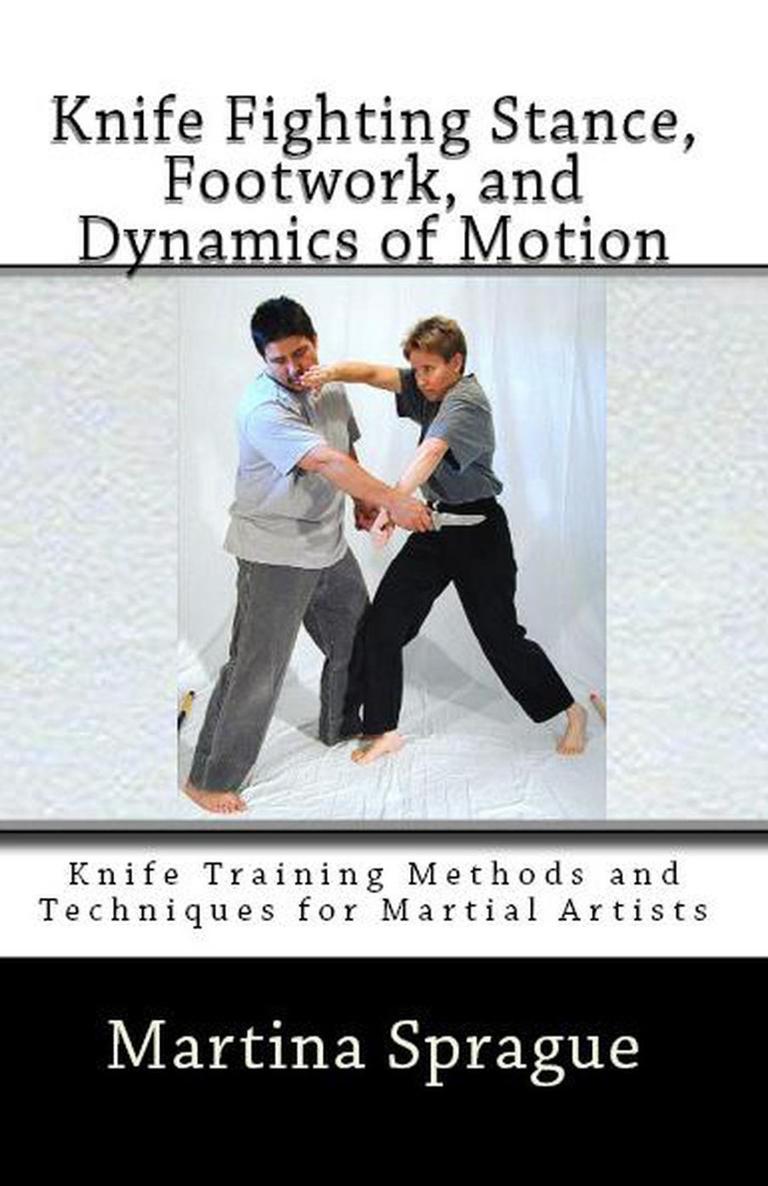

Knife Fighting Stance, Footwork, and Dynamics of Motion

Book

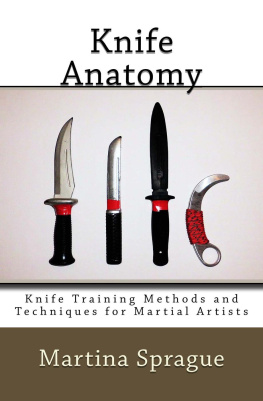

Knife Training Methods and Techniques for Martial Artists

by Martina Sprague

Copyright 2013 Martina Sprague

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the author.

Disclaimer: Always use caution and never use real knives when practicing the martial arts exercises in this book. The reader assumes full responsibility for injuries incurred by doing the exercises described herein, and for the use or misuse of any information contained in this book. The author does not endorse the use of edged weapons as a means for resolving conflict. The instruction in this book is purely informational in purpose and intended to strengthen the martial artists empty-hand skills.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

Brief History

Lesson Objectives

Fighting Stance

Lead or Rear Hand

Basic Movement and Footwork

When You Must Retreat

Movement When Defending Against Kicks and Punches

Lunging Exercise

The Physics of the Stab and Slash

The Physics of Motion and Penetration Depth

INTRODUCTION

Now that you have learned a bit about carrying, deploying, manipulating, and attacking with the knife, we will talk about stance and footwork as related to maneuvering into position for using your previously learned skills.

Stance and footwork give the martial artist the ability to control distance and protect vital areas against enemy attack. Stance and footwork give you control of the engagement, regardless of whether you are up against a knife-wielding or empty-handed fighter. Stance and footwork enable you to change the direction of the attack, flee, or evade an opponents counterattack. Stance and footwork have a major effect on your safety. I caution against getting too fancy with the footwork, however. Remember that knife fighting is not like a sparring match in a controlled environment; it is not about exchanging blows. Your intent is to finish the fight with a single strike if possible.

The particular stance and footwork you use depends to an extent on the size and primary usage of the weapon. Some bigger fighting knives, such as the Nepalese kukri, are designed for heavy chopping and are capable of severing limbs with a single blow. These weapons are therefore extraordinarily difficult to defend against. The use of smaller knives, such as folders and certain daggers, require the use of good footwork to help the wielder attain a position that is beneficial for executing a quick stab or slash, or a series of stabs and slashes. Although the knife is a touch weapon and a single stab or slash with a small knife can prove devastating, a single cut does not necessarily end the fight if aimed at a secondary target (as discussed in Book of the Knife Training Methods and Techniques for Martial Artists series). If the opponent is prepared to meet the attack and also has a weapon, it complicates the situation even more.

As a general guideline when training with the knife, use linear footwork and direct attacks and single chops if wielding a bigger knife (kukri, Bowie, machete), and a combination of linear and circular footwork and combined stabs and slashes if using a smaller knife (folder, dagger). Regardless of the length and design of the weapon, practice seizing the initiative and pressing the attack to place your opponent on the defensive and in retreat. If you find it necessary to retreat to avoid an attack, be aware that it is very difficult to move back in a straight line at a speed faster than your opponent can advance.

As explained in Book 1, the Knife Training Methods and Techniques for Martial Artists series has three objectives: The first few books focus on getting to know the knife, its strengths and weaknesses, and on manipulating and using it. The next few books focus on defending against knife attacks. The last few books focus on implementing empty-hand martial arts skills into your knife training, and include scenario-based exercises intended to bring your knowledge into perspective and give you a solid understanding of your strengths and weaknesses when faced with a knife-wielding assailant. Each book starts with an introduction. You are then given the lesson objectives, along with detailed information and a number of training exercises aimed at making you physically and emotionally ready to participate in traditional martial arts demonstrations involving a knife or, if fate will have it, in a real encounter. Remember that it is your responsibility to know and comply with all federal and local laws regarding the possession and carry of edged weapons. Ultimately, the purpose of this book series is to emphasize how tradition and culture have affected our views of the martial arts and bring increased understanding of the knife as a weapon of offense and defense, while simultaneously strengthening the martial artists empty-hand skills.

BRIEF HISTORY

Footwork can be either linear or circular. For example, the art of fencing relies mainly on linear footwork, as does the art of medieval European swordsmanship, while the art of Asian sword fighting relies on a combination of linear and circular footwork which gives the sword wielder control of his or her opponents weapon and the opportunity to enter his space at a favorable time. Despite these differences in footwork, the objective both in Europe and Asia is to seize the initiative and take control of the fight.

The distance to the target is another factor affecting stance and footwork. In a thrusting attack with a long weapon such as a fencing foil or bayonet, the wielder might lunge forward with his lead leg and thrust the weapon into his opponent. A drawback of the linear attack with the lunge is that it creates a wide stance, making a quick retreat or change of direction difficult. In a slashing attack with a long weapon such as a sword, the wielder can use a combination of linear and circular or lateral movement. A short weapon such as a knife permits even greater flexibility in stance and footwork.

The thrust with the knife in the forward grip, also called a fencing grip, resembles a fencer gaining reach for thrusting his foil into the target by lunging forward with his lead leg and keeping the rear foot planted. Note that a true fencers lunge is wider than the stance pictured here. Image source: Martina Sprague.

In any combat situation with a knife, whether the weapon is used for thrusting or slashing, distance awareness is crucial and comes in part through training in stance and footwork. A reason why a good fencer is successful is because he or she focuses on a stabbing attack to a vital target and trains to achieve this objective with precision. When his weapon lands on target, also called a he is awarded a point. To achieve his objective, the sport fencer must train extensively in developing his footwork. Although fencing is linear and the contestants move only forward and back along the they learn to advance and retreat with speed. In other words, they have a keen sense of distance at all times. When deciding to attack, they do so when their opponent has little opportunity to distance himself from the attack. An additional benefit of the fencers thrust is that it relies on the shortest distance between the tip of the weapon and the target, which further equates to speed.