Copyright 2013 Nancy Herman

www.nancyhermanauthor.com

All rights reserved.

ISBN-13: 9781490317793

ISBN-10: 1490317791

eISBN: 9781483565910

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013915200

Create Space Independent Publishing Platform

North Charleston, South Carolina

Distributed in the USA

Cover Art by Victoria Faye Alday

To Tom, who kept listening.

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing may be a lonely endeavor, but the luckiest of us have supporters cheering us on from the sidelines.

All We Left Behind: Virginia Reed and the Donner Party would not have been completed without the unflagging enthusiasm of my family: Tom Herman, Eric and Jennifer Crippen, Emily Shotwell, and Brant Boivin. Thank you all for your love and support.

My talented writing friends offered comments and encouragement along the way. Many thanks to first readers Jeanne Ashcraft, Susan Britton, Randall Buechner, William Mueller, Elizabeth Varadan, and Naomi Williams. Additional thanks to later readers Rachel Dillon, Angelica Jackson, Christina Mercer, and Joe Vollmer.

I am especially grateful for the valuable editorial advice I received from Ellen Dreyer, Sands Hall, Mandy Hubbard, and Liza Ketchum.

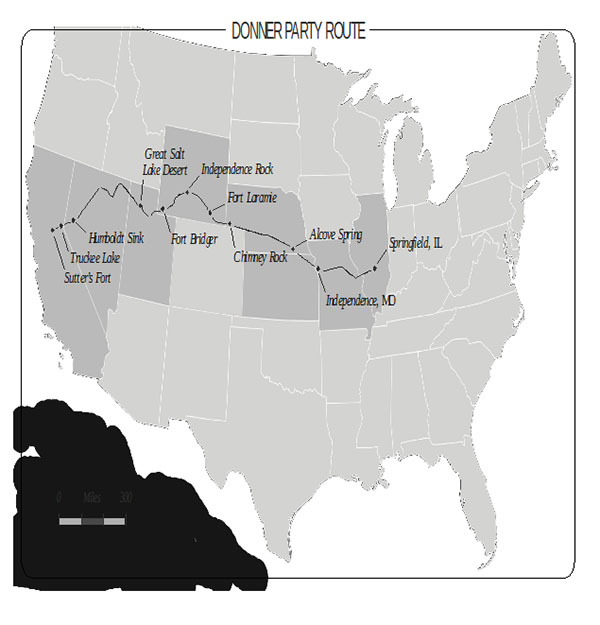

A special thank you goes to Donner Party historian Kristin Johnson for her invaluable feedback, and to all the research librarians, museum curators, and national park and visitor center employees along the Donner Party route who aided me in my research.

O Mary I have not wrote you half of the truble we have had but I hav Wrote you anuf to let you know that you dont know whattruble is.

Virginia Reed, in a May 1847 letter to her cousin Mary Keyes, after reaching California.

Prologue

In my dream I was still cold, even though it was summer and I was back on the plains. Billy was there, sleek and spirited, galloping through the tall grasses. The Sioux boy was astride him, bareback, his hands wound deep into Billys mane.

You found my pony, I cried out.

The boy reined Billy in and lifted his head. His eyes searched the horizon.

Puss. Wake up. Charlies voice.

The Sioux boy caught my eye and waved. Then he and Billy began to fade away.

Dont go, I called.

Someone was shaking me. I cant wake her. Mamas voice rose. I cant wake her, Charlie!

Please dont go, I whispered.

Billy and the Sioux boy vanished.

The daylight hurt my eyes. Mama and Charlie were kneeling over me, their frightened faces close to mine. Between them, through snow-laden branches, I saw a gray-white sky. Morning.

Did the snow stop? I asked.

Oh, thank God, Mama said. She slid her arm beneath my shoulders and gently sat me up.

I was alone in the buffalo-robe bed. The snow had created a thick blanket during the night. Women were digging frantically through drifts, looking for buried supplies. Men were prodding our spent oxen with sticks, forcing them to stand.

Everyone was moving in slow motion. Except for the distant sound of a woman weeping, the scene was eerily silent.

Mama hovered closer. It took a long time to wake you, she said softly. She rubbed my arm as though to thaw me out.

Something inside me began to sink.

Is everyone getting ready to go through the pass?

Mama dropped her hand. She turned her head away.

Charlie? I said.

The answer was already in his face.

No, Puss. His voice cracked. The pass is closed. Were trapped.

Chapter 1

April 1846. Home.

I frowned into the mirror above my empty dresser. This dress is so plain. I squirmed beneath the taut linen fabric. And stiff!

The blue plaid cloth hung from a crisp white collar to the middle of my calves and was loosely cinched at the waist. No more scoop-necked, short-sleeved city dresses for me. Mama said theyd be ruined on the trail, and had donated them all to the Methodist Church. Everything else we owned was given away, packed in the wagons out front or, like our bedroom furniture, left behind for the people who bought our house.

Eight-year-old Patty watched me from her stripped bed, porcelain doll in her lap. My parents voices and the clatter of chains rode the early morning chill through our window. A horse whinnied.

I frowned into the mirror again, then turned to Patty. Why do you think Mama made our pockets so deep? I can stick my whole arm down one. And these. I held up a pair of ugly, round-toed ankle boots. Does she think were going to walk all the way to California?

Patty looked down and fumbled with the hem of her dolls silk dress. Are you scared, Puss? she asked.

Scared? I tugged irritably at my sleeves. Not at all.

Well, I am.

Patty scared? Since when? She and our three-year-old brother Tommy had been eager to go pioneering.

I walked across the room and crouched to look into Pattys dark eyes. Watchful, serious. An old soul, our Grandma Keyes called her. Scared of Indians? I asked. Grandma had pioneered through Kentucky when she was little, and shed enjoyed scaring Patty and me with stories of tomahawks, painted faces, and kidnapped children for as long as we could remember.

The Plains Indians arent like Grandmas Indians, I went on, echoing Grandmas words. Grandma says theyll want to trade baskets for buttons and glass beads, things like that.

Patty shook her head. Im not scared of Injuns.

I thought for a moment. Because of what those stupid boys at school said about wolves and grizzly bears?

She bit her lower lip and nodded. I gave her a quick hug and stood up.

Youve no reason to be scared, Patty, I said, returning to the dresser. Pa would never let anything bad happen to us.

Pa had been itching to go West for more than a year, ever since reading pioneer letters in our Springfield newspaper, the Sangamon Journal. After that, he bought a newly published, yellow-covered book called The Emigrants Guide to Oregon and California, written by a man named Lansford Hastings. Hastings glowing descriptions of fertile valleys and year-round sunshine convinced Pa to sell his business and herd the whole family across the frontier. It didnt matter whether or not we wanted to go. Pa wanted to go, and Pa always got his way.

Despite the odd costume, I did want to go. I was twelve, going on thirteen, and Id never been outside the state of Illinois. Besides, Pa had promised I could ride my pony Billy alongside him. Every day. All two thousand miles.

Yesterday Id said good-bye to schoolmates Id known nearly my whole life. And last night our parlor was filled with friends and relatives: Uncle Jim, scowling in disapproval; Aunt Lydia, sad-faced but resigned; and Mary, who was not only my cousin, but also my very best friend.

Youll write me a letter from the trail, wont you? she asked me through watery blue eyes.

I fought the lump in my throat. Mary and I had shed more than enough tears about our separation these last months.

![Blackstone Audio Inc. - Ordeal by hunger: [the story of the Donner Party]](/uploads/posts/book/167807/thumbs/blackstone-audio-inc-ordeal-by-hunger-the.jpg)