Memoirs are by definition a written depiction of events in a persons life. They are memories. All of the events in this story are as accurate and truthful as possible. Many names have been changed to protect the privacy of others. Mistakes, if any, are caused solely by the passage of time.

Copyright 2014, 2017 by Dave Atcheson

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Atcheson, Dave.

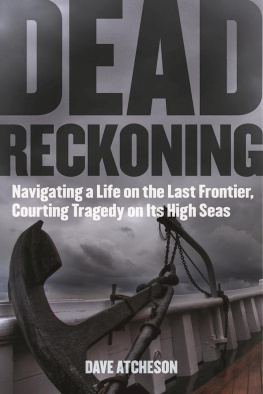

Dead reckoning : navigating a life on the last frontier, courting tragedy on its high seas / Dave Atcheson.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-62873-681-6

1. Fisheries--Alaska--Anecdotes. 2. Fishers--Alaska--Anecdotes. 3. Atcheson, Dave. I. Title.

SH222.A4A88 2014

639.209798--dc23

2014008097

Cover design by Danielle Ceccolini

ISBN: 978-1-5107-2073-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1618-6

Printed in the United States of America

This book is dedicated to all the men and women who seek a different path in life and those who choose to make their living on the sea. It is also dedicated to my family: my sister Leanne and her son Jack; my brother Gordon and his family; Marylou, and my dad, George Atcheson, who has always been there for me and encouraged me to seek out the path less traveled; and for Cindy Detrow, for being there and encouraging me now, with all my love.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD BY ANDY HALL

T HE A LASKAN COMMERCIAL fisherman occupies a special place in the collective consciousness of Americas homogenized, suburbanized, and cubical-bound modern work culture.

Its an idealized vision, realized somewhere up north where a man or woman can still use skill, savvy, muscle, and grit to make an honest living out on the open sea. The reality of it is not quite so romantic. However, whether the result is a net bursting with fish or a water haul, the rewards are plain and uncontested. Such clarity is rare today, and a far cry from the corporate workplace where success seems to be muddled, lost between profit and loss statements and investorrather than customersatisfaction.

Faced with those choices, who wouldnt choose a pitching deck and the cold slap of seawater delivered by a freshening breeze over a career spent spinning on the 8-to-5 gerbil wheel, under the pall of fluorescent lights?

The risks outweigh the rewards in every Alaska fishery I know. The reality of working in the industry is a life of uncertainty, difficulty, and danger. There are no guarantees that one will take home a paycheck, let alone survive. And yet commercial fishing survives and thrives in Alaska, employing more people than any other industry.

The allure is real, and like the taste of an illicit drug, its highly addictive. I was a teenager when I began salmon fishing in the early 1980s. The work was hard but satisfying and, more often than not, lucrative. Between salmon seasons I long-lined for halibut and took more than a few risks. Once, during a three-day opener, my partner abandoned me for the company of an attractive girl. Instead of staying on the beach until he returned, I foolishly went out alone in a sixteen-foot skiff to check and rebait our hooks. As I moved along the mile-long ground line, powered only by the rushing tide, a massive halibut rose to the surface with one of my hooks buried deep in its mouth. The fish outweighed me by at least twenty pounds, and I feared it would injure me if I tried to haul it into the tiny skiff. Id also heard stories of similarly sized halibut bashing holes in boats larger and sturdier than mine.

I watched it thrash, estimated its value at the cannery, and contemplated my next move. With the tide flooding and daylight ebbing, I decided to harpoon the beast. When I drove my spear through its head, the fish erupted into a frenzy of muscular thrashing, shuddering the gunwales and confirming my resolve to somehow get it to shore without letting it into the boat. When it finally spent its energy and calmed down, I lashed its head to the bow then put a loop around its tail and tied the other end to the gunwale. Secured to the exterior of the skiff, the fish spanned almost half the vessels length. With its weight so far forward, it actually lifted the motor out of the water, forcing me to move my fish tote and spare anchors to the stern to keep the prop from cavitating. I started the engine and, with water occasionally spilling over the gunwale, I ran for shore. It was only by the mercy of the wind and waves that I made it to the beach without sinking my skiff. I think I made one hundred dollars for three days of round-the-clock effort.

I fished for almost a decade before my dad convinced me to at least try to put my college degree to use. I did, and left fishing behind to spend the next two decades working at a series of newspapers and magazines around Alaska.

As much as I enjoyed that work, I never quite shook the dream of trading my desk and computer for a skiff and a pile of nets. Over the six years I spent on Kodiak Island editing the paper there, I quietly took classes on outboard motor repair and net mending. One lonely winter I spent almost every free moment rebuilding and restoring a wooden boat in a shop on the outskirts of town. When my son was born, I built him a cradle shaped like a tiny dory on rockers.

Once infected by it, the fishing bug is hard to shake, that much is clear. The why of it though, can be stubbornly indistinct and difficult to articulate.

With great intelligence and insight, Dead Reckoning by Dave Atcheson succeeds at that, shedding light on this mysterious affliction using Atchesons own journey north and his experiences in Alaskas fishing industry. Along the way he masters the intricacies of various Alaskan fisheries, tackles backbreaking work, experiences moments of sublime beauty, and barely survives a harrowing brush with death. Woven together by deft storytelling, the experiences form a gripping, insightful, and authentic chronicle of an Alaskan fishermans existence. Those inside the industry will recognize this story as the real thing. For those still dreaming of venturing north and setting out to sea, its a road map to adventure. Read at your own risk; you just might catch the bug yourself.

Andy Hall is a commercial salmon fisherman and the author of Denalis Howl: The Deadliest Climbing Disaster on Americas Wildest Peak.

INTRODUCTION

A S A HERRING fisherman in the early 1990s, I didnt know I was participating in one of the deadliest fisheries in Alaska, second only to crabbing. But most of us who fish for a living are either not aware of these figures or dont dwell on them, otherwise we might be less inclined to choose it as a vocation. Most of us started out young, longing for adventure and feeling infallible, often falling into a routine, trading long stretches of incredibly hard work for the luxury of month upon month off in a row.